Why Apple’s security works: It locks out both the bad guys and the good guys

[ad_1]

Breaking news: you should keep your doors unlocked so that when you do get robbed—which you totally will—the police can easily get into your house to catch the robbers.

The MIT Technology Review tells us “Hackers are finding ways to hide inside Apple’s walled garden.” (Tip o’ the antlers to Tay Bass.)

That’s not a great headline as it makes a muddled implication about what the article actually states, but the page headline is even worse:

“How Apple’s locked down security gives extra protection to the best hackers.”

One might get the impression from that headline that Apple was helping out hackers. But almost the entire article makes the case that Apple’s security measures work extremely well and are a good thing, so good that it’s being adopted by other companies. It’s mostly just the framing of the headline and introduction that might lead one to believe there was something really wrong with it.

How exactly is Apple supposedly helping those it’s trying to keep out?

…when the most advanced hackers do succeed in breaking in, something strange happens: Apple’s extraordinary defenses end up protecting the attackers themselves.

The point is that because Apple doesn’t allow anyone access across sandboxed instances, so-called “good guys” can’t easily see across those instances to find evidence of hacking. This is true, but it’s also like saying the complicated nature of higher math supports the nefarious insiders club of the Higher Math Industrial Complex.

“Higher math is helping out eggheaded academics by being really complicated! It should be simple enough that everyone can get it!”

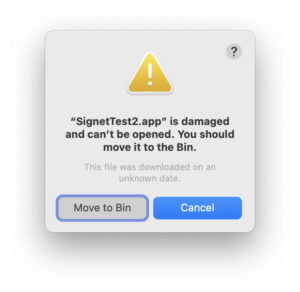

Sometimes the locked-down system can backfire even more directly. When Apple released a new version of iOS last summer in the middle of [Citizen Lab senior researcher Bill] Marczak’s investigation, the phone’s new security features killed an unauthorized “jailbreak” tool Citizen Lab used to open up the iPhone. The update locked him out of the private areas of the phone, including a folder for new updates—which turned out to be exactly where hackers were hiding.

How is that “backfiring”? Jailbreaking relies on exploiting a flaw in the operating system, a flaw that could also be exploited for nefarious purposes. Heck, the flaw that enabled the jailbreak might have been the one used by the hackers Marczak was chasing. And Apple fixed the flaw. Sure, it mades things harder for him to track down that hack, but it protected everyone else who uses an iPhone. Does the argument that Apple should leave vulnerabilities up so that it makes it easier for researchers to reveal hacks make any sense at all?

Dear reader, it does not.

You might be wondering what the alternative that’s being suggested here is. Well, as the article rightly notes, there isn’t one, at least not a good one. Giving “good guys” access to system-level security makes it easier for bad guys to have the same access. So instead of just a few who are managing to hide their tracks from third parties, you’d have hordes of hackers running amok.

The article alludes to it but doesn’t explicitly make the point that because these hacks are so difficult and expensive, only high-profile targets are at any real risk. No one is going to spend millions of dollars to get your cat pictures, Maude. But give Mr. Whiskers a scritch for me.

Most of the article is informative and it ends up making the right point, but focusing the headline and the first half on the inconvenience to researchers is like focusing on the people who get a sore arm from COVID vaccines. The cure is way better than the discomfort of a few.

[ad_2]

Source link