Why does Apple’s ‘change’ feel more forced than transformative?

[ad_1]

Apple gets a lot of flak for its “my way or the highway” approach to, well, pretty much everything: App Store terms, product design, colors, and so on. While that’s an approach that definitely has its benefits—you can tell when committees start getting involved in design, and the end result is rarely good—it also lends itself to a degree of obduracy that can be frustrating for any other parties that have to deal with the company.

But that philosophy doesn’t mean that Apple isn’t willing to make changes when it needs to. Innovation is, after all, another one of the company’s hallmarks, and sitting on one’s laurels in the technology market is rarely a path to success. It’s just that sometimes that change doesn’t from people inside the company, but from external forces.

Lately, the company’s made a number of surprising backtracks against previous policies, and while they might not always be done out of the goodness of its heart—as much as a corporation can be said to have one—it does prove that Apple can learn and perhaps improve…even if it sometimes has to be dragged, kicking and screaming.

Links in a chain

The App Store has been a source of a lot of frustration, especially for developers, but also to a lesser extent for consumers. While the recent Apple versus Epic ruling mainly came up in Cupertino’s favor—and the one provision that Apple did lose is far from a done deal—the company has already made at least some concessions to App Store operation after an investigation from the Japan Fair Trade Commission.

As a result of that investigation, Apple agreed that it would allow “reader apps” (those that require subscriptions to view content) to include a link to their website—something that had previously been against App Store rules. Moreover, that change won’t be limited to Japan, but will roll out globally next year.

While it’s not the most magnanimous of decisions (it’s “an in-app link”, singular, and we haven’t yet seen what the guidelines require) and it’s clear that main impetus was to avoid more scrutiny by regulators, it’s still a positive change that will end up benefiting developers and users alike. And it’s proof that action by the government can indeed force Apple, which is financially larger than many countries, to alter the way it does business. With looming antitrust threats from the U.S. government and the European Union, it does at least lend hope that the company can be nudged to improve itself.

Apple has been stubborn about its App Store policies, but a few small changes have happened.

IDG

Ports in a storm

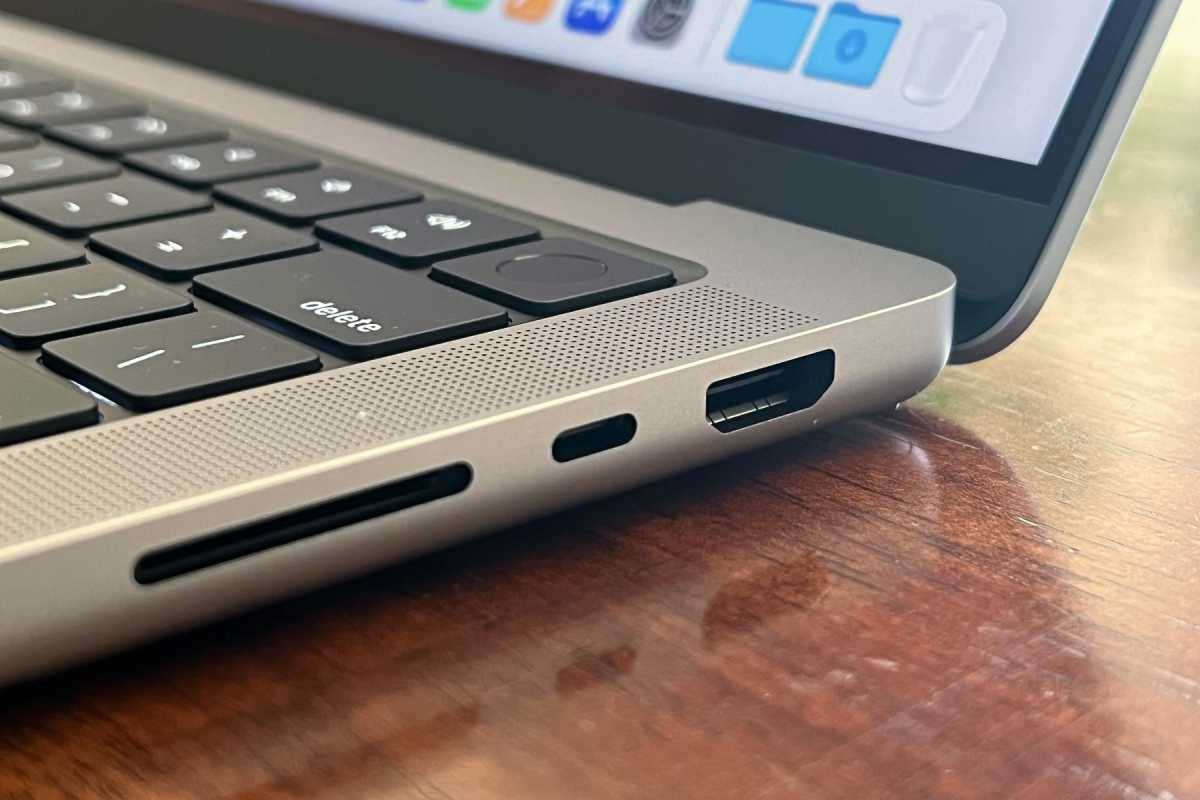

That pressure doesn’t have to come from governments, either. Take the new MacBook Pro as an example. After several years of lackluster models that drew fire for abandoning “legacy” ports and featuring problematic keyboards, Apple rolled out brand new pro laptop models that seems to return those features and address almost all of the aforementioned complaints. It’s almost like the past several years of MacBook Pros didn’t even happen.

While the cynical viewpoint might argue that Apple took all these things away just to be able to turn around and sell them back to us, I’d be a little more charitable: the growing pressure from pro users made the company realize that the product they were making wasn’t the one that most of its customers wanted.

Or, in other words, they hit Apple right in the pocketbook. Not that MacBook Pro sales are a huge part of the company’s bottom line, but the ultimate question is: could they be selling more if they did bring back those features? It’s early yet to know just how well the new laptops have performed, but the reviews have been kind, and when sales numbers ultimately arrive next year, I have no doubt that they’ll back up those assessments.

Apple changed its design for the MacBook Pro for the better.

IDG

Parts in a whole

And so we come to the company’s most recent about-face. After years of insisting that the only way to officially fix your iPhone was via its own AppleCare or an Apple Authorized Service Provider, Apple announced last week that it would make replacement parts, manuals, and tools available to consumers who want to repair their own smartphones. The program begins with certain commonly fixed iPhone 12 and 13 components like the screen, battery, and camera, but will expand over time to include more components and devices, including M1-powered Macs.

As an attentive tech journalist pointed out, this timing wasn’t random, nor was the decision born, once again, of Apple’s altruism. Rather, it was likely prompted by the Securities and Exchange Commission following up on a shareholder resolution that pushed Apple to investigate the impacts of “right to repair” rules. It’s possible that Apple saw the writing on the wall and decided to get ahead of the game by announcing this Self-Service Repair option.

Ultimately, though, I’d argue that the result is more important than the motive. Regardless of how Apple decided to make the change, the company did make it and, as with the App Store and the new MacBook Pro, this move will probably benefit consumers (and, thus in the long run, Apple itself). Even if the company does prefer to do things its own way, it’s clear that external forces can pressure Apple into new behaviors—and that means there’s always hope for change.

[ad_2]

Source link