Arthur: 14 Deaths of Guenevere and Lancelot

Threading their way through many swashbuckling tales of chivalry, Sir Thomas Malory tells four threads, of the life of King Arthur, his love triangle with Queen Guenevere and the faithful adulterer Sir Lancelot, Sir Galahad’s reward of the Holy Grail for his chastity, and the ultimate betrayal of Sir Mordred. Once Arthur had been presumed dead from the wound sustained in the final battle with Mordred, his widowed queen became a nun in Amesbury.

Before they had heard of Arthur’s death, Lancelot, Bors and the other knights who had moved to Benwick were moved by Sir Gawain’s dying words to return to England to avenge that knight’s death, and to avenge the usurped King Arthur and Queen Guenevere. It was only when they reached Dover that they were told of Arthur’s death. Lancelot was then taken to Gawain’s tomb in Dover Castle, where he prayed and lamented.

Lancelot then rode alone until he reached the nunnery where Guenevere had taken orders. The queen saw him, and informed him that she was in the process of healing her soul of her sins. She told him never to look her in the face as long as she was alive, but to return to his lands, marry there and live in joy and bliss. Lancelot insisted on his faithfulness to her, and said that he would find a hermit to take him in. He then asked her for one last kiss, which she refused. They parted in great sorrow.

Dante Gabriel Rossetti (1828–1882), Arthur’s Tomb, or The Last Meeting of Launcelot and Guenevere (1855), watercolour, bodycolour and graphite on paper, 24 x 38.2 cm, The British Museum, London. Wikimedia Commons.

Dante Gabriel Rossetti painted two romanticised versions of Arthur’s Tomb or The Last Meeting of Launcelot and Guenevere: that above is from 1855, and that below from 1860. These depart considerably from the version given by Malory. Following Arthur’s death, Lancelot leans over his tomb and starts to make love to the mourning Queen. The decoration on the side of the tomb shows King Arthur presiding over the Round Table.

Dante Gabriel Rossetti (1828–1882), Arthur’s Tomb, or The Last Meeting of Launcelot and Guenevere (1860), watercolour on paper, 23.5 x 36.8 cm, The Tate Gallery, London. Wikimedia Commons.

Lancelot rode on the following morning until he came to the chapel containing Arthur’s tomb, where the former Archbishop of Canterbury and Sir Bedevere were about to celebrate mass. Afterwards, Bedevere told Lancelot the story of Arthur’s death. Lancelot then asked the Archbishop if he would take him as his brother hermit, which he accepted.

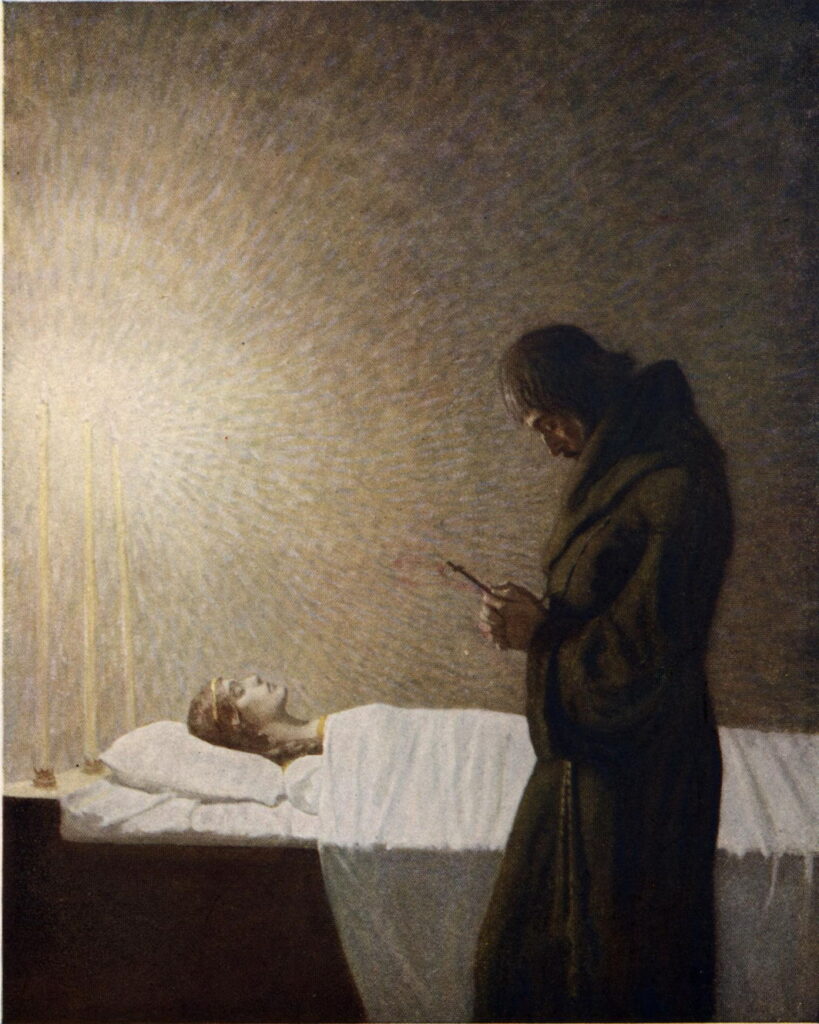

Sir Bors and other knights rode from Dover in quest of Lancelot. Finding him in the chapel, they too became hermits and served penance for the next seven years. One night, Lancelot had a vision that he was summoned to the nunnery at Amesbury, where the queen had just died. He therefore took the other knights with him to that nunnery, where the queen had died only half an hour earlier. They returned with Guenevere’s body, and buried it alongside Arthur in the tomb in the chapel at Glastonbury.

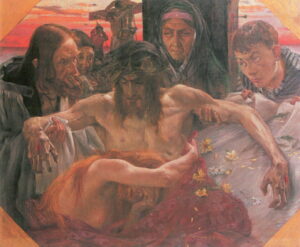

Newell Convers Wyeth (1882–1945), The Death of Guinevere (1922), illustration in “The Boy’s King Arthur: Sir Thomas Malory’s History of King Arthur and His Knights of the Round Table, Edited for Boys” by Sidney Lanier, Charles Scribner’s Sons. Wikimedia Commons.

This illustration of The Death of Guinevere was published in a 1922 retelling graced by the paintings of N.C. Wyeth, brilliant father of the late Andrew Wyeth.

After that, Lancelot ate and drank little, and slowly wasted away. But he had vowed that he would be buried at his castle of Joyous Gard (Malory states this may have been at Alnwick or Bamborough). Lancelot died shortly afterwards, and the Archbishop and the hermit-knights conveyed his body in the same litter that they had used to bring Guenevere’s body to be buried alongside Arthur. Lancelot was buried as he had promised at Joyous Gard.

Malory concludes his account with a summary of the fates of Sir Bors and other knights, who went to the Holy Land, fought battles against the Turks, and died there on Good Friday.

Reference

Dorsey Armstrong (translator and editor) & Sir Thomas Malory (2009) Morte Darthur, a new modern English translation, Parlor Press. ISBN 978 1 60235 103 5. (A superb translation based on the Winchester manuscript.)