Arthur: Summary and Contents

Legends about King Arthur and his knights have a long history across many European cultures. Although there are various accounts of these, the most influential in the last six hundred years is that written by the Englishman Sir Thomas Malory (1414/18-1471) when he was in prison, Le Morte d’Arthur, completed in 1469-70 shortly before his death. His manuscript was rescued from oblivion by William Caxton (c 1422-1491), who brought printing to Britain and, in 1485, printed the first edition.

Paintings of Arthurian legend were few and far between from the Renaissance to the early nineteenth century. Malory’s account fell out of print for over 180 years, until new editions appeared in 1816 and 1817, bringing an Arthurian revival with a succession of illustrated editions and greater popularity than ever before.

William Dyce (1806–1864), Piety: The Knights of the Round Table about to Depart in Quest of the Holy Grail (1849), watercolour and bodycolour over pencil on buff paper, laid down, 23.3 x 44 cm, Scottish National Gallery, Edinburgh, Scotland. Wikimedia Commons.

The established Scottish artist William Dyce suggested to Queen Victoria’s husband Prince Albert that the queen’s robing room in the newly reconstructed Palace of Westminster in London should be decorated with paintings from Malory’s book, and Dyce was commissioned in 1847 to paint them.

Additional literary sources came from the pen of Alfred, Lord Tennyson, who published his initial poetic rendition in two versions in 1832 and 1842, but based those on a thirteenth century Italian novellina rather than Malory. Then in his first Idylls of the King of 1859 Tennyson included the story of Lancelot and Elaine based on Malory’s very different account. Between Malory and Tennyson, artists of the nineteenth century had rich inspiration for their paintings.

Newell Convers (N. C.) Wyeth (1882–1945), “So the child was delivered unto Merlin, and so he bare it forth” (1922), illustration p 4 of ‘The Boy’s King Arthur’, ed. Sidney Lanier, Charles Scribner’s Sons, New York. Wikimedia Commons.

Arthur was conceived when his father, Uther Pendragon, King of England, deceived the Duke of Tintagel’s wife Igraine, as arranged for him by Merlin. He was raised by Sir Ector and his wife, again thanks to Merlin. When King Uther died, he named Arthur his successor, which was confirmed by Arthur drawing a sword from an anvil, a feat no other could accomplish. Arthur was made a knight, and eventually crowned King of England.

John Collier (1850–1934), Queen Guinevere’s Maying (1900), oil on canvas. dimensions not known, Cartwright Hall Art Gallery, Bradford, England. Wikimedia Commons.

Merlin took Arthur to a lake, where an arm in the water held up a sword for him. The sword was named Excalibur, but Merlin explained that its scabbard was the more important, as it would prevent him from losing blood, no matter how severe his wounds.

Before that, Arthur had slept with King Lot’s wife and made her pregnant with Mordred; the king wasn’t aware at that time, but she was his half-sister. The king then fell in love with Guenevere. Despite Merlin warning him that she would fall in love with Sir Lancelot, Arthur and Guenevere were married. Her father promised to give him the Round Table, seating a total of one hundred and fifty knights.

Edward Burne-Jones (1833–1898), The Beguiling of Merlin (1870-4), oil on canvas, 186 x 111 cm, Lady Lever Art Gallery, Port Sunlight, Liverpool, England. Wikimedia Commons.

Merlin fell in love with Nyneve, who eventually abandoned him to die in an enchanted cave. Arthur came into contact with Morgan le Fay, his sister or half-sister, a sorceress who soon managed to take possession of Excalibur and its scabbard, and used them to set up the killing of the king. Nyneve intervened, saving Arthur and revealing the treachery of Morgan le Fay, who had already fled the scene.

Herbert James Draper (1863–1920), Lancelot and Guinevere (1890s), oil on canvas, 51 x 81 cm, location not known. Wikimedia Commons.

Arthur and his knights of the Round Table refused to pay dues to the Roman Emperor, and fought their way across continental Europe to secure that. On their return the young Sir Lancelot proved himself the champion of all the knights, and started his long, devoted but adulterous relationship with Queen Guenevere.

John William Waterhouse (1849–1917), Tristan and Isolde (1916), oil on canvas, 107.5 x 81.5 cm, Private collection. Wikimedia Commons.

Sir Tristram’s uncle was Mark, King of Cornwall. When Tristram (or Tristan) was recovering from wounds, he went to Ireland, where he fell in love with La Beale Isode (La Belle Iseult or Isolde), daughter of the King of Ireland. Later, after Mark and Tristram had fallen out, Mark sent Tristram to bring Isode back for the king to marry. As they were sailing to Cornwall, Tristram and Isode drank together from a cup that ensured their love would never end.

5 Tristram, Isode and the potion

Edmund Blair Leighton (1852–1922), The End of The Song (1902), oil on canvas, 128.5 × 147.3 cm, Private collection. Wikimedia Commons.

After Tristram’s uncle King Mark had married Isode, the knight continued his affair with her. When he tried to live apart from Isode, Tristram found that he was unable to make love to another woman. After Tristram had been banished from Cornwall, he was allowed to return, but King Mark murdered him when he was playing on his harp to Isode.

Sir Edward Burne-Jones (1833-1898), William Morris (1834-1896) and John Henry Dearle (1859-1932), The Arming and Departure of the Knights (1895-96), wool and silk on cotton warp tapestry, dimensions not known, Birmingham Museum and Art Gallery, Birmingham, England. Wikimedia Commons.

Sir Galahad was the son of Sir Lancelot, who had been deceived into making love to Elaine, daughter of King Pelles, thinking that she was Queen Guenevere. He was prophesied as being the greatest knight, and first proved himself by drawing a sword from a stone, justifying his place at the Round Table in its Seat Perilous. After he had demonstrated his skills at jousting, a vision of the Holy Grail appeared in front of the knights, and they all left King Arthur on their quests for the Holy Grail.

Sir Galahad was awarded his shield, with a provenance going back to Joseph of Arimathea and destined for the knight. He then restored order in the Castle of Maidens. Later, Sir Lancelot had a vision of the Holy Grail in an old chapel. Galahad, Bors and Perceval then boarded a ship, where they met Perceval’s sister, who fitted Galahad with his sword. Later the three knights were told that they would be the ones to bring the quest for the Holy Grail to an end.

Edwin Austin Abbey (1852–1911), Galahad at the Castle of Maidens, panel from The Quest and Achievement of the Holy Grail (1893-1902), Arcolor Collotype Litho print of original painting, location of original Boston Public Library, Boston, MA. Wikimedia Commons.

Sir Perceval’s sister was bled to death to restore a lady to health. After a period spent at sea in ships, Lancelot and Galahad met up. A month after they had parted, Lancelot saw the Holy Grail, completing his quest. Galahad met again with Bors and Perceval, and the three finally found the Holy Grail, took it to a ship, and sailed to the city of Sarras. Galahad lived there as king until his death, Perceval became a monk, and only Bors eventually returned to Camelot.

Dante Gabriel Rossetti (1828–1882), How Sir Galahad, Sir Bors and Sir Percival Were Fed with the Sanct Grael; but Sir Percival’s Sister Died by the Way (1864), watercolour and gouache on paper, 29.2 x 41.9 cm, The Tate Gallery, London. Wikimedia Commons.

Lancelot’s affair with Guenevere intensified. When he was away for a tournament, a baron’s daughter, Elaine the Fair Maid of Astolat, fell in love with him. She nursed the knight to recover from wounds he sustained in that tournament, but when he came to leave, Lancelot refused to marry her, or even take her as his lover. She died of a broken heart, and in accordance with her wishes her body was taken by boat to the King and Queen in Westminster, where Lancelot ensured she was buried with honour.

Sophie Gengembre Anderson (1823–1903), Elaine (The Lily Maid of Astolat) (1870), oil on canvas, 158.4 x 240.7 cm, Walker Art Gallery, Liverpool, England. Wikimedia Commons.

Tennyson told a similar story about the Lady of Shalott, who was forbidden from looking directly at the outside world, and confined to weaving at her loom as she watched the world in a mirror. One day she saw Sir Lancelot, and was so taken with him that she looked directly at him. Knowing of her imminent death, she left the castle, boarded a boat, and drifted downstream to Camelot, where Lancelot found her dead.

John William Waterhouse (1849–1917), The Lady of Shalott (1888), oil on canvas, 153 x 200 cm, Tate Britain, London. Wikimedia Commons.

Lancelot’s affair with Queen Guenevere became common knowledge, and his enemies plotted to reveal this treachery to the king. When Sir Meleagant accused Guenevere of treason against the king, Lancelot agreed that they would duel at Westminster to settle the matter. Meleagant then imprisoned Lancelot, who escaped in the nick of time and arrived in London just as Guenevere was being prepared to be burned at the stake. Lancelot killed Meleagant and rescued the queen.

Mordred then tried to expose the affair to Arthur. Despite being unarmed and without armour, Lancelot managed to escape, but had to flee Camelot with a group of knights loyal to him. Arthur condemned the queen to be burned at the stake, but Lancelot rescued her again and took her back to his castle. Arthur besieged them, and they eventually joined in battle, but the Pope intervened and told them to settle peacefully. Lancelot left England and established himself in Benwick, where Gawain and Arthur pursued him.

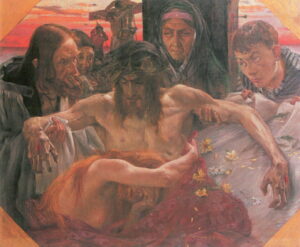

In the meantime Mordred had usurped Arthur’s throne. When Arthur returned, they met in battle. Arthur drove his spear into Mordred, but as the traitor was breathing his last he dealt Arthur a fatal wound to his skull.

William Hatherell (1855-1928), The Rescue of Guinevere (1910), further details not known. Wikimedia Commons.

Sir Bedevere returned Excalibur to the lake, then placed the dying Arthur in a boat that carried him out across the lake, in the company of Morgan le Fay, two other queens, and Nyneve. The following morning there was a fresh tomb in a nearby chapel, apparently containing Arthur’s body.

Edward Burne-Jones (1833–1898), The Last Sleep of Arthur in Avalon (1898), media and dimensions not known, Museo de Arte de Ponce, Ponce, Puerto Rico. Wikimedia Commons.

The widowed Queen Guenevere became a nun. When Lancelot returned from Benwick, he visited her, but she told him never to look her in the face as long as she was alive, and refused to kiss him. Lancelot, Bors and others became hermits serving in the chapel containing Arthur’s tomb. Lancelot had a vision that he had been summoned to the nunnery where the queen had just died, as they indeed did. They brought Guenevere’s body back and buried it with Arthur. Lancelot then pined away and died.

Newell Convers Wyeth (1882–1945), The Death of Guinevere (1922), illustration in “The Boy’s King Arthur: Sir Thomas Malory’s History of King Arthur and His Knights of the Round Table, Edited for Boys” by Sidney Lanier, Charles Scribner’s Sons. Wikimedia Commons.

14 Deaths of Guenevere and Lancelot

Reference

Dorsey Armstrong (translator and editor) & Sir Thomas Malory (2009) Morte Darthur, a new modern English translation, Parlor Press. ISBN 978 1 60235 103 5. (A superb translation based on the Winchester manuscript.)