The best of 2023’s paintings and articles: 2

Apart from my lengthy series about artists from Ukraine, last year brought several series of articles about paintings, and others that you may have missed, or might simply enjoy revisiting. Here are my suggestions from the first half of the year.

Some weekends I like to travel in paintings, and almost a year ago visited the Bay of Biscay.

Henry Moret (1856–1913), Heavy Weather at Saint Grenoble, Point de Penmarc’h (1905), oil on canvas, 73.7 x 100.6 cm, Private collection. The Athenaeum.

It was Henry Moret who specialised in painting the first section of this huge bay, although he came not from Brittany but Cherbourg on the Channel coast of France. His Heavy Weather at Saint Grenoble, Point de Penmarc’h from 1905 shows enormous seas breaking at this point to the south-west of Quimper, marking the northern terminus of a bay noted for its storms and savage seas.

Paintings of the Bay of Biscay 1

Paintings of the Bay of Biscay 2

We’ve become recently concerned with ‘deep fakes’ produced by humans wielding apps like Adobe Photoshop and by AI. Such falsities aren’t recent, and I looked at one French master, Pierre-Narcisse Guérin, who seems to have specialised in them, inventing his own classical Roman character of Marcus Sextus to win himself acclaim at the Salon.

Pierre-Narcisse Guérin (1774–1833), Napoleon Bonaparte Pardoning the Rebels at Cairo, 23rd October 1798 (1808), oil on canvas, 365 × 500 cm, Château de Versailles, Versailles, France. Wikimedia Commons.

In 1806, Napoleon commissioned Guérin to paint for the Gallery of Diana in the Tuileries Palace. The result was Napoleon Bonaparte Pardoning the Rebels at Cairo, 23rd October 1798, completed in 1808.

Napoleon had taken the French army into Egypt in 1798, and conquered Alexandria and Cairo. On 21 October, the citizens of Cairo organised an uprising, and murdered the French commander and Napoleon’s aide-de-camp. The French fought back with artillery, then the cavalry fought their way back into the city, forcing the rebels out into the desert, or into the Great Mosque. Napoleon brought his artillery to bear on the mosque, following which his troops stormed the building, killing or wounding over five thousand. With control restored over Cairo, the leaders of the revolt were hunted down and executed. Following this, the city was taxed heavily in punishment, and put under military rule.

Guérin’s painting shows a quite different event, in which Napoleon is engaged in open discourse with the rebels. However, the presence of French cavalry behind the Egyptians, and the action taking place at the far right, suggests the truth behind this ‘pardon’.

When history is fiction: painted inventions of Pierre Guérin

In March, we spent a weekend with the wonderful but little-known paintings of Maximilien Luce.

Maximilien Luce (1858–1941), Camaret, Moonlight and Fishing Boats (1894), oil on canvas, dimensions not known, Saint Louis Art Museum, St. Louis, MO. Wikimedia Commons.

Luce painted this outstanding nocturne of Camaret, Moonlight and Fishing Boats in 1894. Camaret-sur-mer is a small fishing port in the far west of Brittany. The tower silhouetted in the distance is the Tour Vauban, a fortification dating back to the end of the seventeenth century, and now a World Heritage Site.

A Weekend with Maximilien Luce’s ‘muscular’ paintings 1

In September 2022, I started a series looking at the reading of various features in paintings, as an open-ended iconography. In March, I looked at different ways that artists incorporated their signatures and dedications into their work. Among these is a touching allusion to the marriage of two famous musicians.

Lawrence Alma-Tadema (1836–1912), A Priestess of Apollo (c 1888), oil on canvas, 34.9 x 29.8 cm, The Tate Gallery (Bequeathed by R.H. Williamson 1938, London. © The Tate Gallery and Photographic Rights © Tate (2016), CC-BY-NC-ND 3.0 (Unported), http://www.tate.org.uk/art/artworks/alma-tadema-a-priestess-of-apollo-n04949

Lawrence Alma-Tadema often found ingenious pictorial locations and devices for his signature. In 1888, he painted A Priestess of Apollo as a wedding present for Sir Charles Hallé (1819-1895), the famous conductor who founded the Hallé Orchestra in 1858, and his second wife, the widowed violinist Wilma Neruda. He wrote his dedication to the couple in the graffiti inside the arch.

Reading Visual Art: 41 Signatures and dedications

We tend to assume that the paintings we see today appear as the artist intended. In a series titled Not Like That I looked at those we know have become changed, some mutilated beyond recognition.

Masaccio (1401–1428), Reconstruction of the Remains of the Polyptych of Pisa (1425-6). Wikimedia Commons.

In February 1426, Masaccio was commissioned to paint a large and complex polyptych altarpiece for a chapel in the church of Santa Maria del Carmine in Pisa, and spent much of that year working on it. It appears to have been completed by the end of 1426, but in the 1700s it was dismantled and its individual paintings dispersed. Masaccio’s design was centred on The Virgin and Child with Four Angels, and this reconstruction shows how the eleven panels so far identified were probably placed. It’s thought to have originally consisted of a total of twenty panels.

My major series for the first half of the year assembled the fragments of the Trojan Epics, including those from Homer and Virgil, into what’s believed to be the major narrative cycle of Europe. Over 2,500 years after it was first recorded, its stories continue to be themes for paintings.

Louis Billotey (1883-1940), Iphigenia (1935), media and dimensions not known, Musée d’Art et d’Industrie de Roubaix, Roubaix, France. Wikimedia Commons.

Louis Billotey (1883-1940), who had won the Prix de Rome in 1907 but is now forgotten, painted his version of Iphigenia in 1935. This shows the intended sacrifice of Agamemnon’s daughter in order to gain favourable winds for the Greeks to sail against Troy. Clytemnestra looks far distant at the left as she leads her daughter towards the sacrificial altar beside her. Artemis, marked only by her bow and hunting dog, stands at the right, as the deer runs past.

Henri-Paul Motte (1846–1922), The Trojan Horse (1874), oil on canvas, 96 x 147 cm, Private collection. Wikimedia Commons.

Henri-Paul Motte’s Trojan Horse from 1874 shows the much later scene when the Greeks leave their wooden horse in Troy, in their successful bid to seize control of the city from within.

In March, I showed the wonderful paintings of another largely forgotten artist of the early twentieth century, Théo van Rysselberghe.

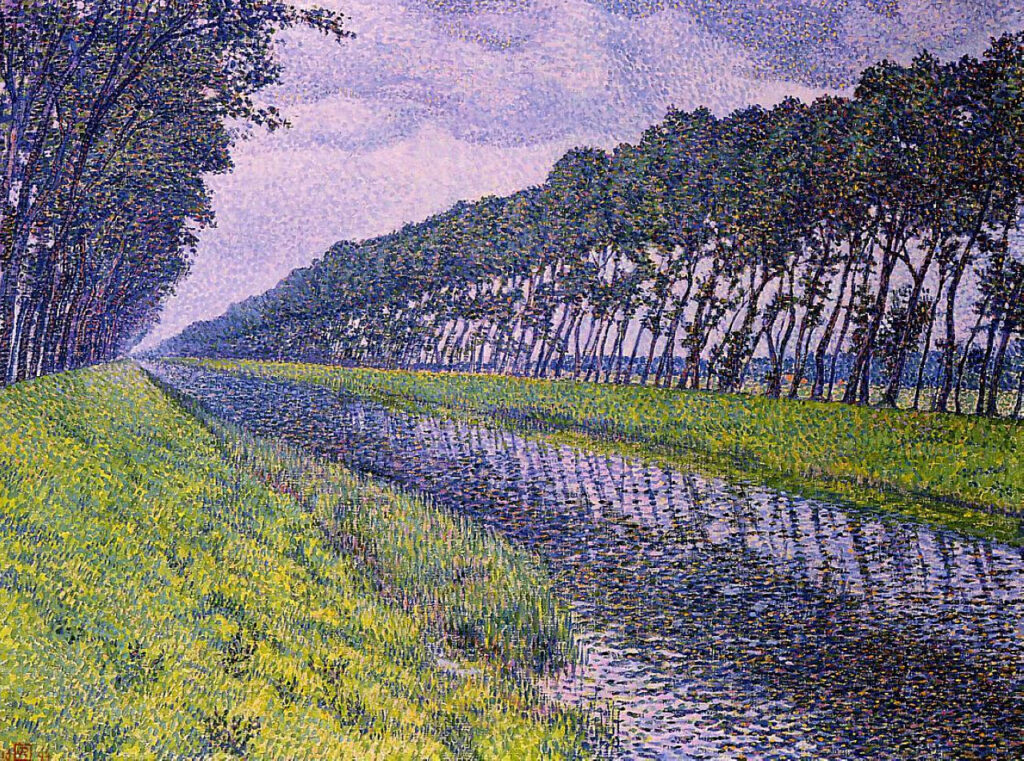

Théo van Rysselberghe (1862-1926), Canal in Flanders (1894), oil on canvas, 152.4 x 203.2 cm, Private collection. WikiArt.

The finished version of his Canal in Flanders (1894) is an amazing combination of radical perspective projection, finely observed and composed trees (carefully adjusted from his earlier sketch), and meticulous reflections, all constructed using tiny marks of contrasting colours. It should surely be rated as a classic depiction of trees, and one of the great Divisionist masterpieces.

Glowing with the Paintings of Théo van Rysselberghe 1: 1880 to 1908

Each summer, I look in greater detail at the work of an artist whose paintings are familiar, but not known well enough. Last summer it was the turn of Eugène Delacroix, among whose many masterworks is The Death of Sardanapalus, completed almost two centuries ago, and seen here in a later replica.

Eugène Delacroix (1798–1863), The Death of Sardanapalus (small copy) (1844), oil on canvas, 73.71 × 82.47 cm, Philadelphia Museum of Art, Philadelphia, PA. Wikimedia Commons.

Based on the climax of Lord Byron’s play about the downfall of the last of the great Assyrian monarchs, Delacroix chose to paint a very different account. Instead of showing Sardanapalus and Myrrha mounting the funeral pyre, Delacroix places the king on a huge divan, surrounded by the utter chaos and panic as his guards massacre wives and courtesans. With these scenes of carnage and destruction all around him, Sardanapalus rests, recumbent on his great divan. His face is mask-like, unmoved, and he stares coldly into the distance, his head propped by his right hand.

Delacroix’s critics were merciless, and no aspect of the painting survived unscathed. Even those who had previously supported his Salon paintings found reasons to disavow him. Its composition of small groups arranged about its central diagonal, its brilliant colours dominated by the red of the king’s divan, its overall effect, all were torn apart by its provocation. Underlying them all was the message that Sardanapalus had gone too far, perhaps most of all by the king’s total disinterest in the slaughter taking place around him.

Paintings of Eugène Delacroix: 0 Contents and summary

In another episode on the reading of visual art in June, I took the Cornucopia, or Horn of Plenty, as the theme. Although this has appeared in many paintings, the most detailed and magnificent account of its mythical origin is modern, and was painted in 1947 for a department store in Kansas City by Thomas Hart Benton, in his Achelous and Hercules.

Thomas Hart Benton (1889–1975), Achelous and Hercules (1947), tempera and oil on canvas mounted on plywood, 159.7 × 671 cm, Smithsonian American Art Museum, Washington, DC. Wikimedia Commons.

At the centre, Hercules, stripped to the waist and wearing denim jeans, is about to grasp Achelous’ horns. Immediately to the right, Deianira is shown in contemporary American form too, with a young woman next to her bearing a laurel crown. They’re sat on the Horn of Plenty, and Benton is one of few painters to have included that important reference.

To the left of centre, Benton shows a second figure of Hercules holding a rope, making this multiplex narrative. That figure is part of a passage referring to ranching and cowboys, and further to the left to the grain harvest. To the right, the Horn of Plenty links into the cultivation of maize (corn), the other major crop from the area.

In a department store in Kansas City.

Reading visual art: 62 Cornucopia

Tomorrow I’ll present my selection from the second half of the year.