Reading visual art: 103 Sport old and mythical

Many civilisations have held competitive sports in high esteem, and it’s only to be expected that they feature in myths, literature and the paintings derived from them. In today’s article I show examples of paintings of sports of the past, mythical and real, and tomorrow’s sequel considers those more genteel sports that became popular during the nineteenth century.

The first of these myths was held to account for the origin of the hyacinth flower, thus an aetiological myth, in the shameful passion of Apollo for the young Spartan, Hyacinthus. One midday, Apollo and Hyacinthus undressed as they were wont to do prior to athletics, oiled their limbs, and threw the discus together. Apollo used his divine powers to throw his high through the clouds.

As his discus was falling, Hyacinthus ran out to catch it, unthinking of its likely speed and energy. The discus ricocheted from the hard earth and struck him in the face, inflicting a mortal wound. The youth went white as he bled from his wounds, and Apollo blanched too as he tried to arrest Hyacinth’s haemorrhage. Thus the blood of Hyacinthus became the purple hyacinth flower, and was commemorated in the festival of Hyacinthia.

Jan Cossiers (1600–1671), The Death of Hyacinth (1636-38), oil on canvas, 97 × 94 cm, Palacio Real de Madrid (Palacio de Oriente), Madrid, Spain. Wikimedia Commons.

Jan Cossiers, who was assisting Rubens in his retirement with some of his remaining projects, painted this finished version of The Death of Hyacinth (1636-38) from Rubens’ oil sketch. The first signs of plants growing in Hyacinthus’ blood appear under the dying youth’s right shoulder.

Giovanni Battista Tiepolo (1696–1770), The Death of Hyacinthus (c 1752-53), oil on canvas, 287 × 232 cm, Museo Thyssen-Bornemisza, Madrid, Spain. Wikimedia Commons.

The most complete narrative painting of this story must be Tiepolo’s magnificent The Death of Hyacinthus (c 1752-53). Tiepolo has been inspired by an Italian translation of the Metamorphoses from 1561, which changed the discus into a tennis ball, actually from the popular game of pallacorda.

The classical story is told in the right foreground, with the pale Hyacinthus visibly bruised on his cheek, but hardly in the throes of death. Apollo is swooning above him, and the Cupid to the right also seems to have suffered some facial injury, perhaps in sympathy. Above that group is a grinning Pan, in the form of a Herm, and a brightly coloured parrot, who seems to have escaped from another story.

On the left of the painting are a motley group of witnesses, wearing the most extraordinary headgear and clothing. Tiepolo does manage to show some hyacinth flowers, at the bottom right corner, at the foot of which are the racquet and balls. The colour of those flowers is far from that of Tyrian purple, as given in the text, but may of course have faded over time.

When Adonis questioned his lover Venus as to why he should keep clear of wild beasts, she told him the myth of the race between Hippomenes and Atalanta.

As a girl, Atalanta had always outrun the boys. But she had been told by an oracle that she should not marry; if she didn’t refuse a husband’s kisses, then she would be deprived of her self. She therefore lived alone, and issued the challenge that she would only marry the man who was faster than her, and beat her in a running race.

Hippomenes was the great-grandson of Neptune, a fast runner, and on first seeing Atalanta’s lithe body, fancied he might be able to beat her, and so win her hand in marriage. When he saw her run, though, he realised how fast, and beautiful, she was. He challenged her. When she had looked him over, she was no longer sure that she wanted to win, thinking whether she might marry him. But she was mindful of the prophecy, and left in a quandary. Hippomenes prayed anxiously to Cytherea (Venus), seeking her help in his challenge. She gave him three golden apples from a tree in Cyprus, and instructed him how to use them to gain an advantage over Atalanta.

The race was started with the sound of trumpets, and the two shot off at an astonishing pace. Atalanta slowed every now and again, to drop back and look at Hippomenes, then reminded of the prophecy, accelerated ahead. Hippomenes threw the first of the golden apples, which Atalanta stopped to pick up. This allowed Hippomenes to pass her, but she soon caught him up and went back into the lead. He repeated this with the second golden apple, and again Atalanta stopped to retrieve it, lost her lead, but caught it up again.

On the last lap, he threw the third apple even further away. Venus intervened and forced Atalanta to chase the apple still further this time, and made it even heavier to impede her progress. This allowed Hippomenes to win the race, and claim Atalanta as his prize. But Hippomenes failed to give thanks to Venus for her intervention. This angered the goddess, and when the couple were travelling back a few days later, Venus filled Hippomenes with desire for Atalanta. They were passing by a temple to Cybele, next to which was an old shrine in a grotto. There Hippomenes made love to Atalanta, so defiling the shrine, and offending Cybele. As punishment, the couple were transformed into a lion and lioness to draw Cybele’s chariot.

Guido Reni (1575–1642), Hippomenes and Atalanta (1618—19), oil on canvas, 206 x 297 cm, Museo Nacional del Prado, Madrid, Spain. Wikimedia Commons.

Guido Reni’s Hippomenes and Atalanta from 1618—19 shows Atalanta picking up the second of the golden apples. He concentrates on their form, specifically the alignment of their limbs and bodies, echoing in their right arms, and his right hand with her left hand. There are also effective contrasts, between their legs and the alignment of torsos, to emphasise their relative motion.

Noël Hallé (1711–1781), The Race between Hippomenes and Atalanta (1762-65), oil on canvas, 321 x 712 cm, Musée du Louvre, Paris. Wikimedia Commons.

Noël Hallé’s Race between Hippomenes and Atalanta (1762-65) goes further in every respect. The scene is now of almost epic proportions, spread across a panoramic canvas. At the right are the local dignitaries, and a winged Cupid as a statue, watching on. Atalanta is still, though, picking up the second golden apple, with Hippomenes holding the third behind him, in his right hand, as if he is about to drop it.

The Trojan Epics give several accounts of funeral games held in honour of the many heroes who died. Among those was Achilles’ great friend, Patroclus.

Carle (Antoine Charles Horace) Vernet (1758-1836), Funeral Games in Honour of Patroclus (1790), further details not known. Image by David Moran, via Wikimedia Commons.

Carle Vernet, son of Claude Joseph and father of Horace, painted his grand vision of the Funeral Games in Honour of Patroclus in 1790. A chariot race is taking place in the left foreground, as Achilles stands proud to the right of centre. In the distance is the great walled city of Troy.

Spartan warrior culture placed importance on competition in sport, as depicted in one of Edgar Degas’ early history paintings.

Edgar Degas (1834–1917), Young Spartans Exercising (c 1860), oil on canvas, 109.5 x 155 cm, The National Gallery (Bought, Courtauld Fund, 1924), London. Image courtesy of and © The National Gallery.

Degas’ starting point for Young Spartans Exercising (c 1860) was the writings of Plutarch, whose account of the Spartan leader Lycurgus and the training of Spartan children was the probable reference. Four Spartan girls, on the left, are seen taunting five Spartan boys, on the right, who appear to pose but not yet to respond to the taunts of the girls. Behind, in the centre of the painting, a group of Spartan mothers are in discussion with Lycurgus himself, who wears a white robe and has his back to the viewer. In the left distance is Mount Taygetus, where unfit Spartan babies were abandoned to see if they survived and merited life.

The modern Olympic Games are the pinnacle of sporting achievement in most athletic events, and a re-invention of those popular in ancient Greece, including the Isthmian Games.

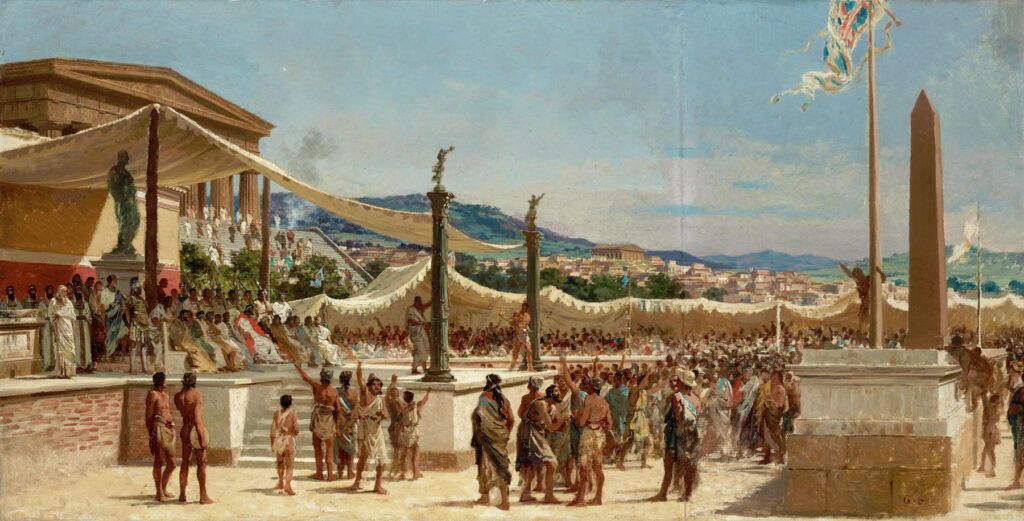

Giuseppe Sciuti (1834–1911), Titus Quinctius Offers Liberty to the Greeks (1879), oil on canvas, 83 x 195 cm, location not known. Wikimedia Commons.

Giuseppe Sciuti’s Titus Quinctius Offers Liberty to the Greeks from 1879 recreates in fine detail the moment that Greece was made free within the Roman Empire, at the Isthmian Games.

The Roman concept of games became increasingly corrupted, until they became occasions for the oppression and murder of minorities such as Christians.

Jean-Léon Gérôme (1824–1904), Circus Maximus (1876), oil on panel, 86.5 x 155 cm, Art Institute of Chicago, Chicago, IL. The Athenaeum.

It was the Romans who not only coined the name circus, but transformed older and purer athletic events into spectacle soaked with sweat and blood, as recreated by Jean-Léon Gérôme in his Circus Maximus of 1876. This shows four-horse chariot racing taking place in the largest of all the stadiums in Rome, capable of holding a crowd of over 150,000.

With the demise of the Roman Empire, organised sport in Europe faded through the Middle Ages, but games and sports continued to flourish among children.

Pieter Brueghel the Elder (1526/1530–1569), Children’s Games (1560), oil on wood, 118 x 161 cm, Kunsthistorisches Museum, Vienna, Austria. Wikimedia Commons.

Pieter Brueghel the Elder painted his compendium of Children’s Games in 1560, also shown in the detail below. Until you study his figures carefully, you might not notice that this work is an illustrated encyclopaedia of the games of childhood at the time.

Pieter Brueghel the Elder (1526/1530–1569), Children’s Games (detail) (1560), oil on wood, 118 x 161 cm, Kunsthistorisches Museum, Vienna, Austria. Wikimedia Commons.

Tomorrow we leap forward two hundred years.