Reading visual art: 106 A life in bed, love

Given the amount of time we spend in them, relatively few paintings show beds. Many of us are conceived, born, recover from illness, finally succumb and die in beds, and we also spend a not insignificant minority of our lives in them. In this and the next article tomorrow, I first look at some beds of importance, then move on to their strongest association, with love, pleasure and procreation. Tomorrow my focus will be more on their role in sickness, and at the end of life.

Eugène Delacroix (1798–1863), The Death of Sardanapalus (1827), oil on canvas, 392 × 496 cm, Musée du Louvre, Paris. Wikimedia Commons.

Eugène Delacroix’s masterpiece of The Death of Sardanapalus (1827) shows that doomed king on a vast bed, surrounded by half-naked women, servants, slaves, and his court, as his empire crumbles around him. This is a thoroughly romantic revision based on Lord Byron’s dramatisation of events interpreted and elaborated much later by the Greek historian Diodorus Siculus.

Gerard ter Borch (1617–1681), The Messenger (Unwelcome News) (1653), oil on panel, 66.7 x 59.5 cm, Koninklijk Kabinet van Schilderijen Mauritshuis, The Hague, The Netherlands. Wikimedia Commons.

Gerard ter Borch’s The Messenger, popularly know as Unwelcome News, from 1653, shows a young couple in front of their bed. The young man at the left is still booted and spurred from riding to deliver a message to them. Slung over his shoulder is a trumpet, to announce his arrival and importance. The recipient wears a shiny breastplate and riding boots, and is taken aback at the news brought by the messenger. His wife leans on her husband’s thigh, her face looking serious.

The scene is the front room of a house in the Golden Age. Behind them is a traditional bed, typical in living areas at the time, with some of their possessions resting on a table between the couple and their bed. Hanging up on a bedpost is the husband’s sword, and behind them is a gun and powder horn.

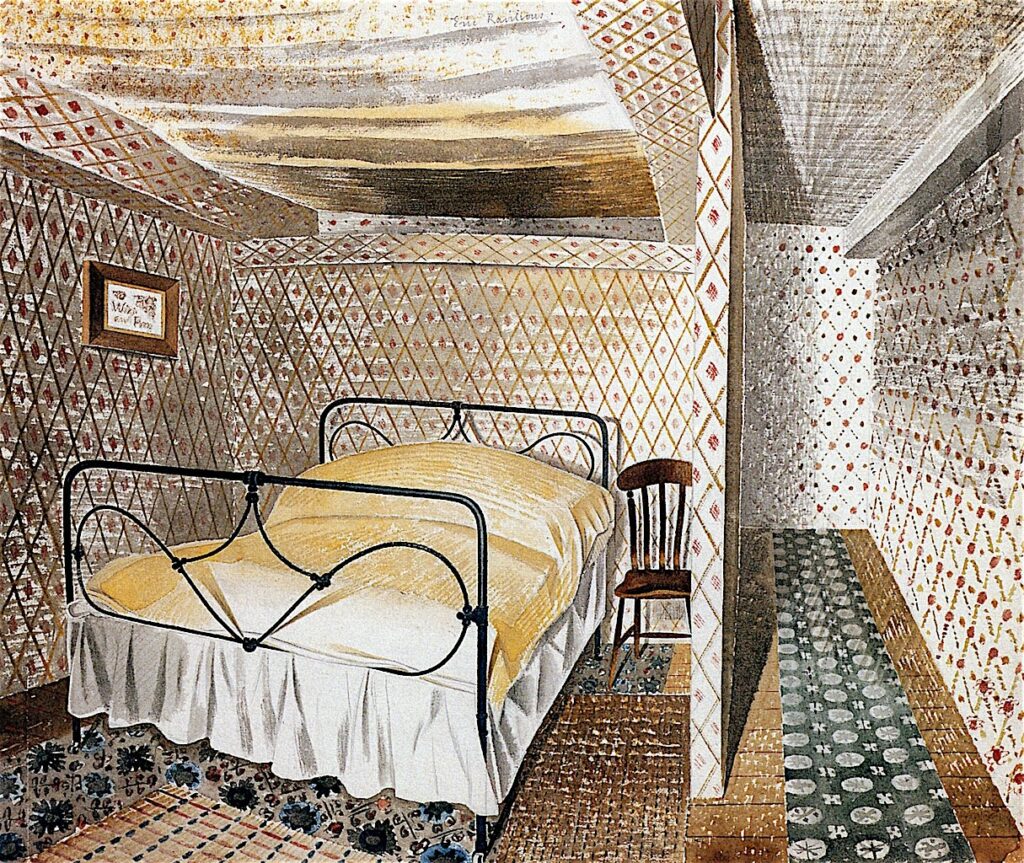

Just at the outbreak of the Second World War, Eric Ravilious developed his occasional paintings of domestic interiors into a series of beds. In these, traditional wooden chambers and luxurious ‘four-poster’ beds enveloping their occupants with rich drapes, were replaced by wrought iron bedsteads turned out by a modern factory, and open to the world.

Eric Ravilious (1903–1942), The Bedstead (1939), watercolour, further details not known. Wikimedia Commons.

The Bedstead (1939), with its wide angle projection, is full of patterns: the wallpaper, floorboards and rugs.

Eric Ravilious (1903–1942), Farmhouse Bedroom (1939), watercolour, further details not known. Wikimedia Commons.

In his Farmhouse Bedroom (1939) the patterns almost overwhelm, and its projection is so extreme that it distorts.

In older paintings from the Northern Renaissance, the occasional appearance of a bed was in strict association with holy matrimony.

Jan van Eyck (c 1380/90-1441), Portrait of Giovanni Arnolfini (?) and his Wife (1434), oil on oak panel, 82 x 59.5 cm. The National Gallery, London. Wikimedia Commons.

Jan van Eyck’s most famous painting, known as The Arnolfini Wedding (or similar variations), is a remarkable exploration of optics, featuring distorted reflections in the mirror near the centre of the painting, completed in 1434. This newly-wed couple stand holding hands next to their marital bed, and there’s the suggestion that she is already well into her first pregnancy.

John Collier (1850–1934), Mariage de Convenance (1907), oil on canvas, 124 x 165 cm, Cyfarthfa Castle Museum & Art Gallery, Merthyr Tydfil, Wales. The Athenaeum.

Sadly, marriage wasn’t always as happy, or well-intended. John Collier’s problem picture Mariage de Convenance (1907) received extensive media coverage. A mother, dressed in the black implicit of widowhood, stands haughty, her right arm resting on the mantlepiece. Her daughter cowers on the floor, her arms and head resting on her bed, in obvious distress. Perhaps the daughter has been (or is to be) married into money to bring financial security to the family, now that the father is dead?

Joachim Wtewael (1566–1638), Mars and Venus Surprised by the Gods (c 1606-10), oil on copper, 20.3 x 15.5 cm, J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles, CA. Wikimedia Commons.

Joachim Wtewael is not only known for his ostensibly unpronounceable surname, but for his remarkably explicit figures. In his Mars and Venus Surprised by the Gods from about 1606-10, he gives a full visual account of the story of the adultery of Mars and Venus, and leaves the viewer in no doubt as to what the couple were doing in her marital bed, even adding a flush to her cheeks.

He uses multiplex narrative too: Vulcan is seen forging his fine net in the far background, and again at the right, as he is about to throw the finished net over the couple. Mars’ armour is scattered over the floor, and there is a chamber-pot under the bed. Behind Vulcan the other gods are arriving, and laughing with glee at the raunchy scene being unveiled to them.

It wasn’t until the start of the twentieth century that Wtewael was outdone by Pierre Bonnard’s painted account of his relationship with his partner Marthe.

Pierre Bonnard (1867-1947), Man and Woman (c 1900), oil on canvas, 115 x 72.5 cm, Musée d’Orsay, Paris. The Athenaeum.

Bonnard developed his earlier Man and Woman in an Interior into his Man and Woman from about 1900. Marthe isn’t getting dressed, but sits up in the sunshine with her legs in a position reminiscent of that in Indolence, below, spreading her thighs. On the bed in front of her are small stuffed toy animals, including a cat with a red ribbon around its neck. A folded wooden screen divides the painting into two. Bonnard stands at the right edge of the painting, his legs appearing skeletal in the sunlight.

Pierre Bonnard (1867-1947), Woman Dozing on a Bed (‘Indolence’) (1899), oil on canvas, 96 x 105 cm, Musée d’Orsay, Paris. The Athenaeum.

Bonnard’s Woman Dozing on a Bed or Indolence of the previous year shows Marthe lying relaxed on a double bed, implicitly after their lovemaking. She lies with her right hand tucked behind her neck and her left hand below her right breast. As her right foot dangles off the side of the bed, her left almost grips her lower right thigh, spreading her legs and exposing her sex. A brown blanket lies at the foot of the bed, it and the sheet wrinkled where the couple had been in bed together. The artist makes his presence known by wisps of blue smoke from his pipe, scattered around the edges of the painting.

Henri Gervex (1852–1929), Rolla (1878), oil on canvas, 175 x 220 cm, Musée des Beaux-Arts, Bordeaux, France. Wikimedia Commons.

In 1878, Henri Gervex submitted to the Salon the painting for which he is now most famous: Rolla. There would have been nothing wrong with this nude had she been in a classical setting, but like Manet’s notorious Olympia (1863) before, her contemporary surroundings and the heap of clothes beside her were deemed immoral. This was inspired by a poem by Alfred de Musset about a prostitute, and Gervex depicted her asleep in bed as her client gets dressed the following morning. Their clothes are mixed together, and tumble onto the floor beside her. In the end, Gervex got a commercial gallery to exhibit this painting, where it attracted far more attention than it would have in the Salon.

Edgar Degas (1834–1917), Interior (‘The Rape’) (1868-9), oil on canvas, 81.3 x 114.3 cm, Philadelphia Museum of Art, Philadelphia, PA. Wikimedia Commons.

A single bed plays a key role in Edgar Degas’ enigmatic Interior, also known as The Rape, from 1868-9.

A man and a woman are in a bedroom together. The woman is at the left, partly kneeling down, and facing to the left. Her hair is cropped short, she wears a white shift that has dropped off her left shoulder, and her face is obscured in the dark. Her left forearm rests on a small stool or chair, over which is draped a dark brown cloak or coat. Her right hand rests on a wooden cabinet in front of her. She appears to be staring down towards the floor, off the left of the canvas.

The man stands at the far right, leaning on the inside of the bedroom door, and staring at the woman. He is quite well-dressed, with a black jacket, black waistcoat and mid-brown trousers. Both his hands are thrust into his trouser pockets, and his feet are apart. His top hat rests, upside down, on top of the cabinet in front of the woman.

Between them, just behind the woman, is a small occasional table, on which there is a table-lamp and a small open suitcase. Some of the contents of the suitcase rest over its edge. In front of it, on the table top, is a small pair of scissors and other items which appear to be from a small clothes repair kit (‘housewife’). The single bed is made up, and its cover is not ruffled, but it may possibly bear a bloodstain at the foot. At the foot of the bed, on its large arched frame, another item apparently of the woman’s clothing (perhaps a coat) is loosely hung. On that end of the bed is a woman’s dark hat with ribbons.

Beds also played key roles in several of Gustave Courbet’s commissioned erotic paintings, earlier in the century.

Gustave Courbet (1819–1877), The Sleepers (1866), oil on canvas, 135 x 200 cm, Petit Palais, Paris. Wikimedia Commons.

Courbet’s The Sleepers from 1866 was commissioned by Khalil Bey, a rich collector of erotica, and is one of several of Courbet’s paintings for which Joanna Hiffernan modelled. It was exhibited by a picture dealer in 1872, when its explicit lesbian motif resulted in a police report. The painting was removed from sight of the public for over a century, until 1988.

We have come a long way from the marital bed of the Arnolfinis.