The Breaking Wave in Paintings 1

Nature has many wonderful forms, of which the near-breaking wave is one of the most fascinating. Unless you were an artist in central Europe who didn’t get out much, chances are that you’d have witnessed these forms, even if their scale wasn’t too impressive. Yet artists seldom painted prominent near-breaking waves until the latter half of the nineteenth century, when a single woodblock print was unintentionally imported to Europe: Katsushika Hokusai’s print of The Great Wave of Kanagawa, first made in Japan in about 1830-31. This weekend I celebrate the influence that had over European painting.

Water waves were among the earliest physical phenomena to be painted, in the ancient and classical civilisations around the Mediterranean, which provided an endless source of models. Although those artists must have seen near-breaking waves, prior to the middle of the nineteenth century, waves generally appear confused: impressive, atmospheric, but lacking that characteristically beautiful form.

Claude Joseph Vernet (1714–1789), A Storm on a Mediterranean Coast (1767), oil on canvas, 113 × 145.7 cm, J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles, CA. Wikimedia Commons.

As far as I can see, it was the marine painter Claude Joseph Vernet who first made a serious attempt at capturing the form, here in A Storm on a Mediterranean Coast from 1767. He has grasped all their essential features, such as their increasing transparency towards the crest, and their breaking, and these look thoroughly convincing.

Ivan/Hovhannes Aivazovsky (1817–1900), The Ninth Wave Девятый вал (1850), oil on canvas, 221 x 332 cm, State Russian Museum Государственный Русский музей, Saint Petersburg, Russia. Wikimedia Commons.

Another artist who placed great emphasis on accurate form is the prolific marine painter of the nineteenth century Ivan or Hovhannes Aivazovsky. His best-known painting The Ninth Wave from 1850 contains a visual reference collection of wave forms, lightly influenced by Gericault’s Raft of the Medusa.

Japan’s eastern seaboard is exposed to the Pacific Ocean, which despite its name is often far from being pacific, with large waves generated by frequent storms. They had been depicted in Japanese art since the sixteenth century, forming their own sub-genre of painted screens known as ariso byōbu, or ‘rough seas screens’.

Katsushika Hokusai (葛飾北斎) (1760–1849), (Springtime in Enoshima) (1797), woodblock print, further details not known. Wikimedia Commons.

In about 1797, the woodblock print-maker Katsushika Hokusai (葛飾北斎) (1760–1849) started developing motifs from this theme, with his print of Springtime in Enoshima. Here the small and densely-vegetated island of Enoshima is seen at the end of its sand spit, with the snowy cone of Fuji in the far distance. Just about to crash on the beach is a regular wave, a precursor to the most famous Japanese work of art in the West.

Katsushika Hokusai (1760–1849), Kanagawa-oki Honmoku no zu (View of Honmoku off Kanagawa) (1803), woodblock print, dimensions not known, Sumida Hokusai Museum, Sumida, Japan. Image by Sailko, via Wikimedia Commons.

By about 1803, Hokusai’s attention had moved further south and east along the coast to another island, Kanagawa, from where he made this print of a View of Honmoku off Kanagawa. The wave has grown into a monster, its talons reaching out from the crest at a cargo vessel sailing along its trough. Two years later came the parent of his most famous print, then in around 1830 he struck gold.

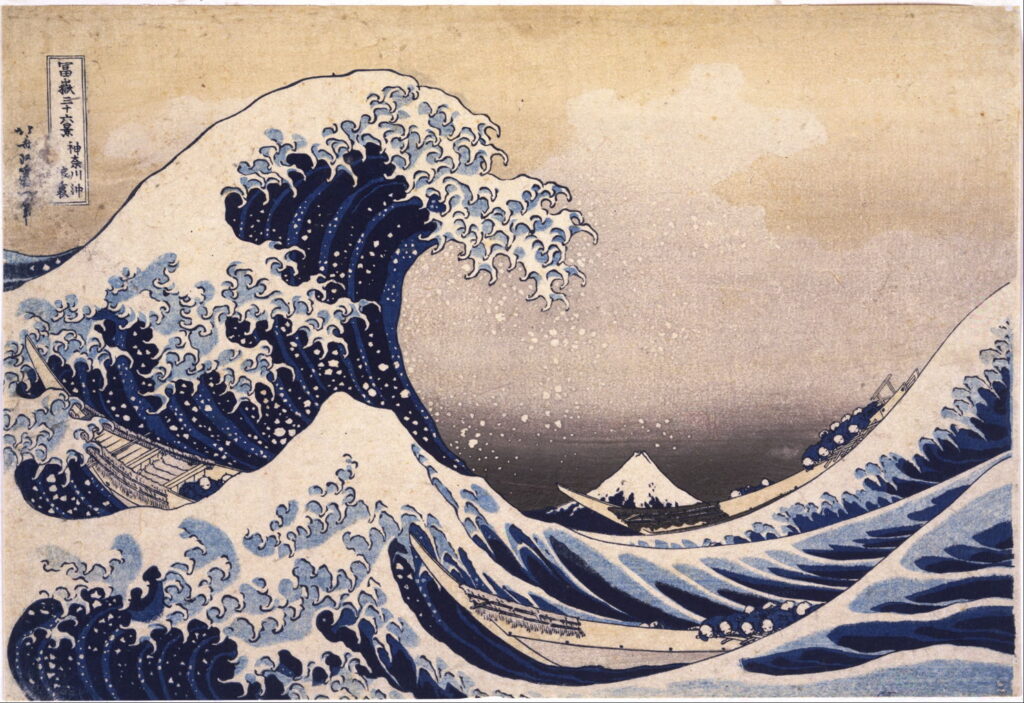

Katsushika Hokusai (1760–1849), 神奈川沖浪裏, Kanagawa oki nami ura (The Great Wave off Kanagawa) (Edo, 1830-32), woodblock print, 25.7 x 37.9 cm, Tokyo National Museum 東京国立博物館, Tokyo, Japan. Wikimedia Commons.

Hokusai’s Great Wave off Kanagawa (Edo, 1830-32) was included in the collection Thirty-six Views of Mount Fuji, and proved popular not only in its home market, but also in Europe, when it arrived there more than twenty years later.

Katsushika Hokusai (1760–1849), The Big Wave (100 Views of Mount Fuji – Kaijô no fuji, vol 2) (1838), woodblock print, dimensions and location not known. Wikimedia Commons.

That wasn’t the last of Hokusai’s versions of this motif either: a few years later it appeared as The Big Wave in his 100 Views of Mount Fuji.

Utagawa Hiroshige (歌川 広重) (1797–1858), 七里ヶ浜 – Shichirigahama (The Seven-Ri Beach) (c 1835), woodblock print, no. 6 of the series Famous Places of the Sixty-odd Provinces, further details not known. Wikimedia Commons.

Other masters of ukiyo-e took up this theme too: Utagawa Hiroshige (歌川 広重) (1797–1858) was one of the last. In this view of The Seven-Ri Beach, from about 1835, looking towards Enoshima and Fuji from the east, he includes a similar regular wave just about to break on a small group of people.

No one knows when Hokusai’s Great Wave first appeared in Europe. Although it’s sometimes claimed that this didn’t happen until the re-opening of Japan to the West with the Meiji Restoration in 1868, there are records of the first ukiyo-e prints reaching the hands of artists in France more than a decade earlier.

They appear to have arrived as protective wrapping for porcelain, and in about 1856 the French artist Félix Bracquemond, also an accomplished print-maker, first came across Hokusai’s prints at the workshop of his printer. Japonism spread rapidly through artistic circles in Paris and other European cities. Among those who collected these prints were Bracquemond, Vincent van Gogh, Claude Monet, Edgar Degas, Gustav Klimt, Édouard Manet, and Paul Gauguin.

Gustave Courbet (1819–1877), Autumn Sea (1867), oil on canvas, 54 x 73 cm, Ohara Museum of Art 大原美術館, Kurashiki, Japan. Wikimedia Commons.

In the late 1860s, Gustave Courbet’s coastal paintings came to concentrate more on the waves breaking on the beach, as in his Autumn Sea from 1867.

Gustave Courbet (1819–1877), The Wave (1869), oil, dimensions not known, Städelsches Kunstinstitut und Städtische Galerie, Frankfurt, Germany. Wikimedia Commons.

Then in 1869 Courbet painted a breaking regular wave that must surely have at least been influenced by Hokusai’s print.

Gustave Courbet (1819–1877), Waves (c 1870), oil on canvas, 72.5 x 92.5 cm, National Museum of Western Art 国立西洋美術館 (Kokuritsu seiyō bijutsukan), Tokyo, Japan. Wikimedia Commons.

Appropriately, this development of the motif, in Courbet’s Waves from about 1870, is now in Tokyo, where it should perhaps be exhibited alongside Hokusai’s Great Wave.

Following Courbet, near-breaking waves swept across the art of Europe, as I’ll show tomorrow.