Changing Paintings: 8 Aglauros turned into stone

Having warned us of the consequences of gossip about others, Ovid turns in the later sections of Book 2 of his Metamorphoses to consider related sins. He leads into this with a short account of Mercury’s theft of Apollo’s herd of cattle resulting in Battus being turned to stone, then tells the last complete myth in this book, of Mercury’s love for Herse leading to her jealous sister Aglauros undergoing the same transformation.

Apollo has a herd of cattle, but instead of watching them carefully, he has fallen in love and is more interested in playing his reed pipes. His herd wanders off to Pylos, Mercury spots them, and seizes the opportunity to drive them into a wood. The only witness to this is an old man named Battus, whom Mercury takes aside and gives a cow in return for his silence.

Mercury then goes away, and returns in disguise. He offers Battus a cow and bull if he gives him information about the missing herd. Battus immediately tells him where they are, so Mercury transforms him to stone for his treachery.

Mercury flies off to witness the crowds attending the festival of Apollo. Among them, he sees a beautiful young woman, Herse, who takes his fancy. He flies down to her house, which has three bedrooms decorated with ivory and tortoiseshell, for each of the three daughters of Cecrops, Herse, Aglauros, and Pandrosos.

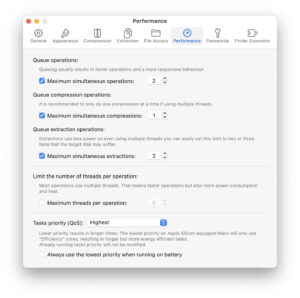

Jacob Pynas (1592/1593–c 1650), Mercury and Herse (c 1618), oil on copper, 21 x 27.8 cm, Galleria degli Uffizi, Florence. Wikimedia Commons.

Jacob Pynas’ tiny oil on copper painting of Mercury and Herse (c 1618) shows the god flying high above the crowds of women attending the festival.

When he arrives at their house, Aglauros is the first to greet him. Mercury explains who he is, and tells her that he has come to visit and marry her sister Herse. Ovid here reminds us that it was Aglauros who had earlier broken Minerva’s instruction to not open the basket containing the infant Ericthonius. As Aglauros now asks Mercury to pay her a fortune to let him in to visit her sister, Minerva sees the opportunity to get revenge on Aglauros by poisoning her with envy. Mercury now courts Herse, with jealousy brewing in her sister Aglauros’ heart.

Louis-Jean-François Lagrenée the Elder (1725-1805), Mercury, Herse, and Aglaurus (1767), oil on canvas, dimensions not known, Nationalmuseum, Stockholm, Sweden. Image by Osama Shukir Muhammed Amin, via Wikimedia Commons.

In Louis-Jean-François Lagrenée the Elder’s painting of Mercury, Herse, and Aglaurus from 1767, the god is making rapid progress in his courtship, as a sour-faced Aglauros spies on the couple from behind a drape.

Aglauros then sits herself outside Herse’s door, and refuses to move to allow Mercury past. For her obstruction of Mercury, and her festering jealousy, Mercury transforms Aglauros into stone.

Hendrick van Balen the Elder (1573–1632) (attr), Herse and her Sisters with Mercury (c 1600-32), oil on panel, 29.2 x 21 cm, Private collection. Wikimedia Commons.

Hendrick van Balen the Elder’s Herse and her Sisters with Mercury (c 1600-32) shows the god at the right, trying to negotiate his way past Aglauros. In the foreground, Pandrosos and their maids prepare Herse to welcome Mercury in her best sandals and finest clothes.

Paolo Veronese (1528–1588), Hermes, Herse and Aglauros (1576-84), oil on canvas, 232.4 x 173 cm, The Fitzwilliam Museum, Cambridge, England. Wikimedia Commons.

Paolo Veronese’s Hermes, Herse and Aglauros from 1576-84 shows Mercury, with his distinctive winged hat, trying to push his way past Aglauros, who is guarding the doorway to Herse.

Jan Baptist Huysmans (1654–1716) and Jan Erasmus Quellinus (1634–1715), Mercury Turns the Jealous Aglaurus into Stone (c 1700), oil on canvas, 122 x 102 cm, Musée des Beaux-Arts de Marseille, Marseille, France. Wikimedia Commons.

Jan Baptist Huysmans and Jan Erasmus Quellinus, in their Mercury Turns the Jealous Aglauros into Stone (c 1700), cram the action into the relatively small entrance of their inventive image of the Cecrops house. It’s hard to know who is doing what, or to whom, but Mercury appears to be standing inside the threshold, with Aglauros running towards him from outside. Herse sits and watches from a window at the left, and the statue of a man stands to remind us of her sister’s imminent fate.

Jean-Baptiste Marie Pierre (1714–1789), Mercury, Herse and Aglaurus (1763), oil on canvas, dimensions not known, Musée du Louvre, Paris. Wikimedia Commons.

Jean-Baptiste Marie Pierre’s Mercury, Herse and Aglauros of 1763 is clearer, and devotes the whole of the canvas to the figures and their story. Mercury has just arrived at the right, amid a cloud of smoke. Aglauros is falling at the right, under Mercury’s caduceus, and is presumably in the midst of being transformed into stone.

This leads us into the final passages of Book 2, starting the story of the rape of Europa.