Painting the circus: performance and spectacle

At about this time in early Spring, travelling circuses around the northern hemisphere start to break out of their winter quarters and migrate to cities to bring entertainment to the masses. Much-changed now from their form in their heyday in the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, they were among the earliest forms of mass entertainment, long before movies.

Jean-Léon Gérôme (1824–1904), Circus Maximus (1876), oil on panel, 86.5 x 155 cm, Art Institute of Chicago, Chicago, IL. The Athenaeum.

It was the Romans who not only coined the name, but transformed older and purer athletic events into spectacle soaked with sweat and blood, as recreated by Jean-Léon Gérôme in his Circus Maximus of 1876. This shows four-horse chariot racing taking place in the largest of all the stadiums in Rome, capable of holding a crowd of over 150,000.

These lived on in fairs throughout the Middle Ages and later, but it wasn’t until the late eighteenth century that the modern circus started to take shape. Itinerant street performers, riders and others who visited fairs were organised by pioneers like Philip Astley and Andrew Ducrow into coherent performances. These events took place in buildings like the London Hippodrome, and the Amphithéâtre Anglais in Paris. In the early nineteenth century, some took to travelling from city to city, performing under canvas tents centred on the Big Top.

Honoré Daumier (1808–1879), The Parade, or Street Circus (c 1860), watercolour on paper, 26.6 × 36.7 cm, Musée du Louvre, Paris. Wikimedia Commons.

Among the early painted accounts of this form of entertainment is Honoré Daumier’s caricature of The Parade, or Street Circus from about 1860. This shows a group of mountebanks, theatrical performers, musicians, and clowns who drew large crowds. Their facial expressions and gestures are theatrically exaggerated, but the narrative less apparent. The crocodile suggests it may be one of the Pulcinello or Punch and Judy shows, with origins in the commedia dell’arte, that became popular among street performers in several European countries including France, and North America.

Painting the action from inside the Big Top is a great challenge, particularly at a time when it wasn’t possible to photograph moving bodies in such low light.

Émile Friant (1863–1932), The Entrance of the Clowns (1881), media and dimensions not known, Private collection. The Athenaeum.

One of Émile Friant’s earliest works is this 1881 painting of The Entrance of the Clowns, showing the interior of the Big Top at the moment that the clowns, acrobats, and other entertainers parade. The artist has carefully put the foreground into relatively sharp focus and detail, and left the background blurred and sketchy, as may have been influenced by photography.

James Tissot (1836-1902), Women of Sport (The Amateur Circus) (1883-5), oil on canvas, 147.3 x 101.6 cm, The Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, MA. Wikimedia Commons.

Following James Tissot’s return to Paris, he included in his successful series of large paintings about the modern woman this view of Women of Sport (The Amateur Circus) from 1883-5. This derivative of the circus seems to have used notable members of the public as its performers, and Tissot places even greater emphasis on the reaction of the spectators.

In 1872, Ferdinand Beert (1835-1902), popularly known as Fernando, started a circus in Vierzon, France, which he moved to Paris the following year, then into purpose-built premises on the edge of Montmartre in 1875. Cirque Fernando became popular among artistic and literary circles, including several of the French Impressionists. Fernando’s wife encouraged this by giving artists free access to both rehearsals and performances, where they could sketch freely.

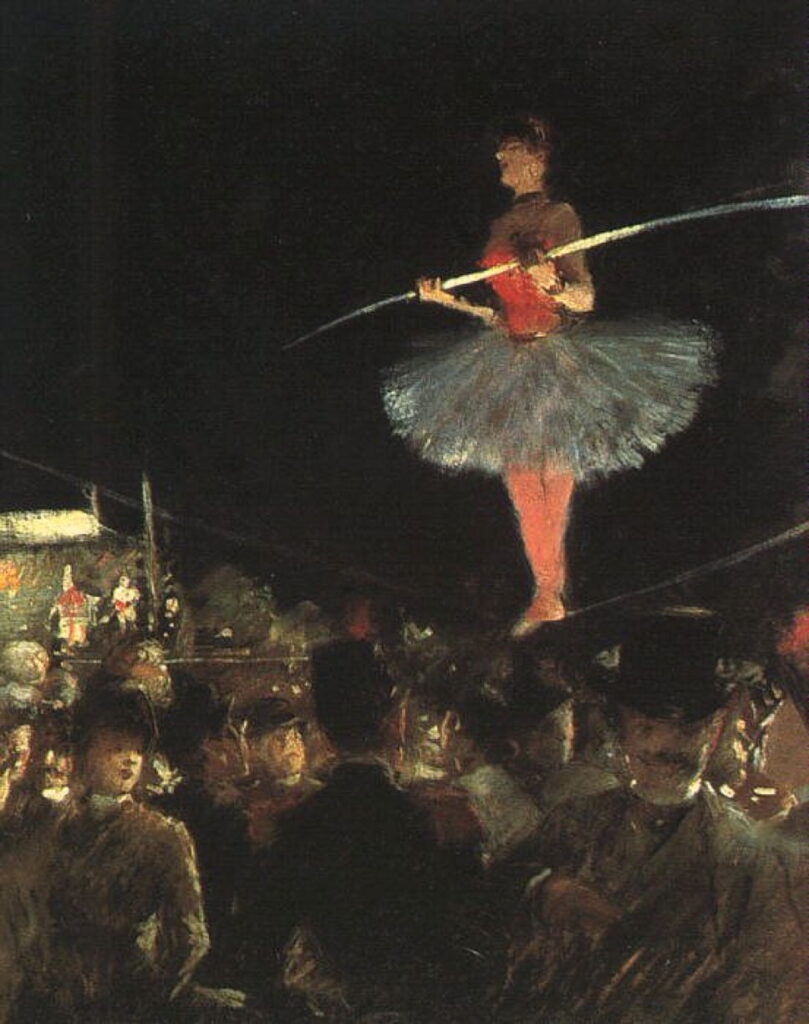

Jean-Louis Forain (1852–1931), The Tight-Rope Walker (c 1885), oil on canvas, 46.2 x 38.2 cm, Art Institute of Chicago, Chicago, IL. Wikimedia Commons.

I’m not sure whether Jean-Louis Forain’s atmospheric painting of The Tight-Rope Walker from about 1885 is set in the Cirque Fernando, but it’s skilfully composed with the dramatically-lit performer in the upper half, and a packed house below.

Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec (1864–1901), The Rider at the Cirque Fernando (1888), oil on canvas, 98 x 161 cm, Art Institute of Chicago, Chicago, IL. Wikimedia Commons.

One of the artists who frequented the Cirque Fernando was Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec. In his Rider at the Cirque Fernando of 1888, Fernando’s son Louis is the ringmaster looking at one of his equestrian performers, who’s riding side-saddle in a typically skimpy costume.

Georges Seurat (1859–1891), The Circus (1891), oil on canvas, 185 x 152 cm, Musée d’Orsay, Paris. Wikimedia Commons.

Georges Seurat’s The Circus from 1891 is one of the masterpieces of Divisionism, and may also depict a scene in Cirque Fernando. Its internal contradiction is the artist’s choice of a painstakingly slow and mechanical method of painting, for a motif that is full of spontaneous movement and action.

Boris Dmitrievich Grigoriev (1886-1939), In the Circus (1918), media and dimensions not known, St. Petersburg State Museum of Theatrical and Musical Art Санкт-Петербургский государственный музей театрального и музыкального искусства, Saint Petersburg, Russia. Image by shakko, via Wikimedia Commons.

Many circus performances were aimed at adult audiences, with mixed action, danger and more than a pinch of the erotic. This is captured well in Boris Dmitrievich Grigoriev’s 1918 painting In the Circus. Curiously, the following year Lenin expressed his desire that in post-revolutionary Russia, circuses should become the people’s art-form, and they soon became nationalised.

Isaac Israëls (1865–1934), At the Circus (date not known), watercolour, 24.5 x 33.5 cm, location not known. Wikimedia Commons.

Isaac Israëls’ undated watercolour At the Circus dispenses with the action in the ring, and looks at the spectators’ reactions.

Heinrich Zille (1858–1929), Circus Games (1924), coloured lithograph, dimensions and location not known. Wikimedia Commons.

By the early years of the twentieth century, circuses were an established if itinerant part of society. Children in neighbourhoods engaged in circus games, as shown so delightfully in Heinrich Zille’s lithograph Circus Games from 1924.

Beyond the spectacle of the ring, life for performers was often very different, as I’ll consider in tomorrow’s sequel.