What makes a disk bootable?

Once upon a time, I’m sure all you needed to make a disk bootable was a System file and the ‘blessing’ of that disk. Then Apple decided we had to have System Folders, and OS X made it even more complicated. This article outlines what a disk now needs for it to be bootable using a modern Mac.

Intel basics

Making a disk bootable is something we normally leave a macOS installer to fix for us. If you still use a utility like Carbon Copy Cloner or SuperDuper! to clone an existing bootable volume group to a disk, a procedure no longer recommended for Apple silicon Macs, that too should spare you the hassle. But when either goes wrong and you discover that Startup Disk won’t let your Mac start up from that volume group, it’s important to discover what might have gone wrong.

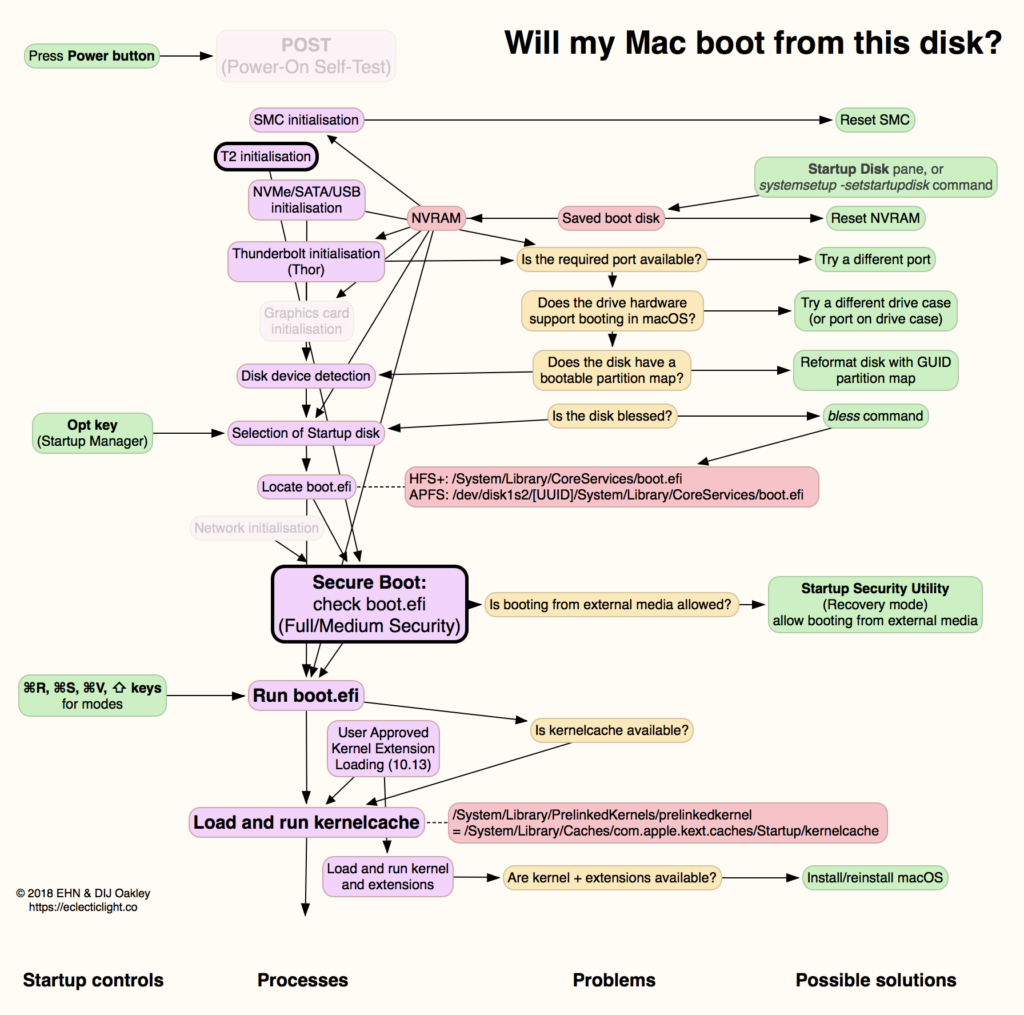

To understand this, consider how an Intel Mac boots from macOS Mojave or earlier, and where that can fail. That’s summarised for older Intel Macs and those with T2 chips in the following diagram.

One fundamental requirement is that the hardware, the Mac’s interface, any cable and drive enclosure, all must support booting that Mac. Some older enclosures offer connections that can’t be used for booting, in which case you’re onto a loser from the start. For T2 Macs to boot from an external disk, that must have been enabled using Startup Security Utility in Recovery mode.

Normally, on a non-T2 Mac booting from an HFS+ disk, it needs a boot loader at /System/Library/CoreServices/boot.efi. A helper partition is normally used when a disk is encrypted using HFS+ FileVault 2, or the storage device requires additional drivers, such as an external RAID array. On a non-T2 Mac booting from an APFS disk, the boot loader should be in the path [UUID]/System/Library/CoreServices/boot.efi on the special Preboot volume /dev/disk1s2.

Bootable disk (Intel)

Starting partially in Catalina, and in full from Big Sur onwards, the required container and volume structure on a bootable disk for an Intel Mac is essentially the same whether it’s internal or external. There’s the traditional hidden EFI partition, and a single APFS container with the boot volume group, consisting of:

the SSV, a mounted snapshot of the unmounted read-only System volume named Macintosh HD, forming the root of the boot file system. The snapshot is named com.apple.os.update- followed by its UUID;

the writable Data volume, by default on the internal disk named Macintosh HD – Data, normally hidden from view at its mount point in /System/Volumes and accessed via firmlinks. On Intel Macs, this is given its full name;

Recovery, the paired Recovery Volume;

Preboot, containing cryptexes and other private files;

VM, containing virtual memory caches.

Note that the Seal on the unmounted read-only System volume is normally broken, but it’s the snapshot that’s important: that should be sealed, unless you have broken its seal intentionally.

Intel Macs still boot into the paired Recovery volume within their boot volume group by holding the Command and R keys during startup. If that fails, the only alternative source of recovery tools is Remote or Internet Recovery, entered with the Command, Option and R keys held.

Bootable disk (Apple silicon)

The internal SSD in an Apple silicon Mac consists of three APFS containers, and lacks the legacy EFI partition. Only the Apple_APFS container is normally mounted, and that has a similar structure to the boot container of an Intel Mac. There are two significant differences, though:

the Data volume isn’t named Macintosh HD – Data, as on an Intel Mac, but plain Data;

the paired Recovery volume is the primary Recovery system for that copy of macOS, and is supported by the fallback Recovery system in the unmounted Apple_APFS_Recovery container.

Apple silicon Macs are distinct in having this fallback Recovery system, making them more robust in the event of damage occurring to the boot container on their internal SSD. Note that in Big Sur the paired Recovery volume isn’t used; instead, the Recovery partition on the internal SSD is the main Recovery system for all bootable systems on that Mac. That was changed to paired Recovery with macOS Monterey and later.

Unlike Intel Macs, M-series Macs always start their boot process from their internal SSD, even when they’re going to complete it from an external bootable disk. This is to ensure that their boot process is secure throughout, using a verified chain of trust through each step in the process.

This starts with the Boot ROM to validate the Low Level Bootloader (LLB), stage 1 of the boot process. The LLB in turn validates other firmware to be used in Stage 2, the LocalPolicy to be applied to the startup disk, and iBoot (Stage 2) itself, in accordance with the requirements of the applicable LocalPolicy. When starting up from a boot volume on an external disk, control is then transferred to that bootable system, which is stored in a single APFS container with the same layout as that for an Intel Mac.

LocalPolicy

The user controls LocalPolicy through Startup Security Utility, which is only accessible in Recovery Mode, and requires user authentication. There is no LocalPolicy that applies to all users and all disks, though: each LocalPolicy is specific to a System Volume Group and authorised user. For example, these can allow:

a single bootable external disk to be used to start up two or more Macs;

one Mac to be started up from any of several System Volume Groups, which can be running older versions of macOS, or load third-party kernel extensions.

Default LocalPolicy created for each bootable external disk provides Full Security, which among other things blocks the loading of third-party kernel extensions and requires SIP to be fully enabled. iBoot (Stage 2) validates kernel collections, signed System volumes, and other components to ensure their integrity, and that the kernel, extensions and macOS to be loaded have an acceptable version number.

LocalPolicy is created when installing macOS to an external disk, when the boot volume group on that disk is assigned its Owner. It can also be created when selecting the boot volume group on a bootable external disk to be the startup disk, in the Startup Disk pane (or in Settings), if it doesn’t already have a valid LocalPolicy, for example when you want to boot from an external disk previously created using another Mac.

LocalPolicy can be changed, in particular changing Secure Boot settings using Startup Security Utility, by first booting from that boot volume group, shutting down, and starting up in Recovery mode. That sequence is essential to ensure that the Mac boots into the Recovery volume paired with the System volume whose security settings are to be changed (Monterey and later).

The current startup disk setting is stored in NVRAM, which on Apple silicon Macs can’t readily be reset by the user. In the event that disk can’t be used to boot that Mac, it will normally fall back to starting up from the internal SSD. This is a more convoluted process in the event that the expected startup disk can’t be found at all: in that case, there will be a long delay in startup, during which the power light will remain on but the display will be black. Eventually, when all hope of finding the missing boot disk is abandoned, the Mac should boot from the hidden Recovery container on the internal SSD, normally used as Fallback Recovery, enabling the user to choose another startup disk and restart from that.

Summary

There’s a great deal more required for an external disk to be bootable than just having a valid macOS installed.

Intel Macs without T2 chips are simplest, but even they now require a complete boot volume group and EFI container/partition. T2 models also require their boot security changed using Startup Security Utility for them to boot from external disks.

Apple silicon Macs are the most complex, in requiring LocalPolicy with an Owner. If that isn’t configured correctly, they won’t be able to boot from that external disk. However, they don’t require to have their Secure Boot settings changed: unlike T2 models, by default they can boot from external disks in Full Security.