A to Z of Landscapes: Lakes

This week, our alphabet of landscape painting has reached the letter L, which stands for lakes that feature in so many of the finest views. With thousands to choose from, I’ve picked a small selection illustrating different approaches, and some of greater significance in art.

First are the idealised landscapes of Nicolas Poussin, that so often give pride of place to lakes.

Nicolas Poussin (1694-1665), Landscape with a Calm (c 1651), oil on canvas, 97 x 131 cm, J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles. Digital image courtesy of the Getty’s Open Content Program.

Poussin used a lake to augment the placid atmosphere in his Landscape with a Calm from about 1651. The upper parts of the Italianate mansion, together with the livestock on the far bank of the lake, are painstakingly reflected on the lake’s surface, telling us that there isn’t a breath of breeze to bring ripples to disturb those reflections.

Frederic Edwin Church (1826–1900), Eagle Lake Viewed from Cadillac Mountain, Mount Desert Island, Maine (1850–60), oil and graphite on paperboard, 29.4 x 44.5 cm, Cooper Hewitt, Smithsonian Design Museum, New York, NY. Wikimedia Commons.

If one lake is great, then the multiple lakes shimmering in Frederic Edwin Church’s Eagle Lake Viewed from Cadillac Mountain, Mount Desert Island, Maine (1850–60) can only be better. Cadillac Mountain is relatively low, at 466 metres (1530 feet), but the highest point of Mount Desert Island, which affords spectacular views such as this.

John Atkinson Grimshaw (1836–1893), Windermere (1863), oil on canvas, 43.3 x 100.3 cm, Yale University Art Gallery, New Haven, CT. Wikimedia Commons.

This painting of Lake Windermere (1863) in the Lake District of north-west England was the making of John Atkinson Grimshaw’s career as a landscape artist. Although not quite still enough for a detailed reflection, the water doubles up the rich colour of the sky.

Eilif Peterssen (1852–1928), Summer Night (1886), oil on canvas, 133 x 151 cm, Nasjonalgalleriet, Oslo. Wikimedia Commons.

Eilif Peterssen painted Summer Night on Fleskum Farm in Bærum during 1886, alongside Harriet Backer, Kitty Kielland, and others. This view of the local lake, Dæhlivannet, became one of his greatest landscape works thanks to it showing the sky with its crescent moon only in reflection.

Albert Bierstadt (1830–1902), A Storm in the Rocky Mountains, Mt. Rosalie (1866), oil on canvas, 210.8 x 361.3 cm, Brooklyn Museum, New York, NY. Wikimedia Commons.

Albert Bierstadt’s A Storm in the Rocky Mountains, Mt. Rosalie, from 1866 shows a technique he used frequently to make a lake appear unreal: a distant band of brilliant reflected light at the foot of the mountains. The foreground shows a pastoral valley floor with a First Nation camp, in mottled light. A small rocky outcrop has trees straggling over it, that are silhouetted against the brilliant sunlight on the lake behind, in the middle distance. Behind the lake the land rises sharply, with rock crags also bright in the sunshine. In the background the land is blanketed by indigo and black storm clouds. Those are piled high, obscuring much of Mount Rosalie, but its ice-clad peaks show proud, high up above the storm, with patches of blue sky above and beyond them.

Joseph Mallord William Turner (1775–1851), The Lake, Petworth: Sunset, Fighting Bucks (c 1829), oil on canvas, 62 x 146 cm, The Tate Gallery (Accepted in lieu of tax 1984, at Petworth House), London. © The Tate Gallery and Photographic Rights © Tate (2016), CC-BY-NC-ND 3.0 (Unported), http://www.tate.org.uk/art/artworks/turner-the-lake-petworth-sunset-fighting-bucks-t03883

JMW Turner’s The Lake, Petworth: Sunset, Fighting Bucks from about 1829 camouflages the lake of its title and washes it in the deep orange of dusk.

Joseph Mallord William Turner (1775–1851), The Blue Rigi, Sunrise (1842), watercolour on paper, 29.7 x 45 cm, The Tate Gallery, London. WikiArt.

Turner’s favourite mountain was Mount Rigi, also known as the Queen of the Mountains, which is almost surrounded by lakes. Among his many late watercolours of the Rigi is this famous view across Lake Lucerne, The Blue Rigi, Sunrise from 1842. The mountain is blue in the early dawn, and the planet Venus shimmers vertically above its peak. The foreground features forms suggesting dogs chasing wildfowl at the shore, and at the right the small lights of fishing boats, but the lake itself is only hinted at by those subtleties.

Paul Cézanne (1839-1906), Le Lac d’Annecy (Lake Annecy) (1896) (R805), oil on canvas, 65 x 81 cm, The Courtauld Gallery, London (Samuel Courtauld Trust) (P.1932.SC.60). Wikimedia Commons.

Cézanne’s Lake Annecy is generally taken as the inception of his most radical style and approach to painting, during his late career. Although he uses traditional repoussoir, the radical effect of his distorted reflections is to bring the far shore closer.

Gustav Klimt (1862–1918), Attersee I (1900), oil on canvas, 80.2 x 80.2 cm, Die Sammlung Leopold, Vienna, Austria. Wikimedia Commons.

In August 1900, Gustav Klimt spent a holiday on Attersee, a resort he was to return to every summer until 1916. In this first visit, he developed his treatment of rippled water in at least two paintings of the lake itself. Attersee I (1900), with its unusual colour harmonies and painstakingly measured brushstrokes, is the better-known of the two.

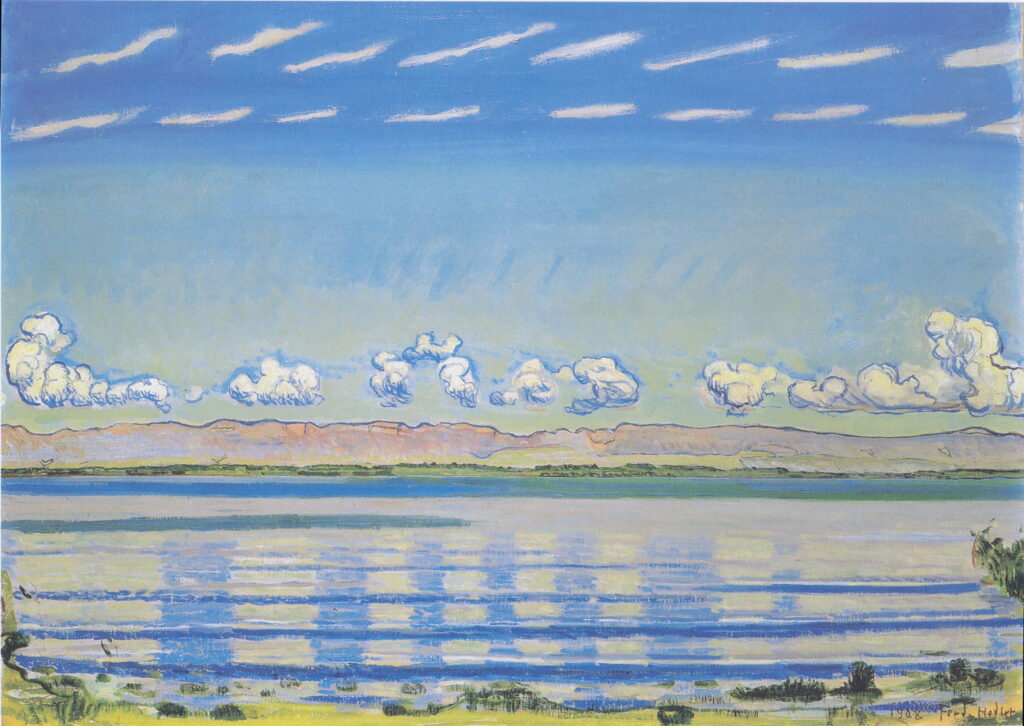

Ferdinand Hodler (1853–1918), Rhythmic Landscape on Lake Geneva (1908), oil on canvas, 67 x 91 cm, Private collection. Wikimedia Commons.

In 1908 when Ferdinand Hodler was in pursuit of Parallelist ideals, he painted this Rhythmic Landscape on Lake Geneva. This was a second version of a view he had previously painted three years earlier, when he wrote “This is perhaps the landscape in which I applied my compositional principles most felicitously.” Much of his symmetry and rhythm is obvious; what may not be so apparent are the idiosyncratic reflections seen on the lake’s surface. The gaps in the train of cumulus clouds here become optically impossible dark blue pillars, responsible for much of the rhythm in the lower half of the painting.

Where would landscape paintings be without lakes?