The Truthful Vision of Jean-Léon Gérôme 5

The first decade of the Third Republic had been a stormy period in France, and by the 1880s the old guard royalists were in decline, and the civic powers of the Republic were expanding to include the provision of free secular education. With Paris well into the Belle Époque, artists divided between those who painted the belles, and those who painted the poor. Jean-Léon Gérôme did neither, preferring instead to tell the story of the stock market crash that forced Paul Gauguin to paint for his living.

The Paris economy and stock market had been generally reckless during the Second Empire, as told so well in the novels of Émile Zola. The Third Republic did little to change that, and during 1880 the market for new securities and forward markets boomed as investors gambled on stock prices continuing to rise. In early 1881, the Union Générale bank fell into difficulties: its stock prices suddenly fell, it was unable to cover its debts, and its public reports were falsified to try to disguise its predicament.

The bank crashed, bringing down with it the entire stock market, leading to the worst crisis in the French economy in the century, and a recession lasting until the end of the decade. Among the many stockbrokers who lost their job was Paul Gauguin. Recognising the impossibility of painting an economic crisis, Gérôme turned to similar but more visual events of the past, in The Tulip Folly (1882).

Jean-Léon Gérôme (1824–1904), The Tulip Folly (1882), oil on canvas, 65.4 x 100 cm, Walters Art Museum, Baltimore, MD. Wikimedia Commons.

The tulip flower, originally a Turkish import, became extremely popular in the Netherlands during the early 1600s. The Dutch cultivated them to produce varieties of different colours, petal and leaf patterns, and these became associated with wealth and status. By 1634, the value of tulips had become very high, out of all proportion to their real worth. Certain varieties in particular became highly sought-after, and the subject of financial speculation. Eventually the bubble burst, prices collapsed, and paper fortunes vanished almost overnight. This resulted in a credit crisis and national financial problems which were a parallel to those in France at that time.

Gérôme shows one group of (government) soldiers in the middle distance, destroying beds of tulips in a move to manipulate the market. In the foreground, an officer stands guard over a pot containing a single rare variety of tulip. His sword is drawn ready, although pointing at the ground just by his valuable plant.

There’s another reading which may not have been Gérôme’s: prices of his paintings had become almost absurdly high. When this work was sold to New York within months of completion, it fetched 50,000 francs, for example. He may well have foreseen the crash in value that would result when his work fell out of fashion, as it did towards the end of the century. This may even have been his warning to speculators that he felt his work had become overvalued.

The following year, Gérôme finally delivered a painting commissioned by the American collector William T Walters in 1863, the last of his spectacular depictions of Rome: The Christian Martyrs’ Last Prayer (1883).

Jean-Léon Gérôme (1824–1904), The Christian Martyrs’ Last Prayer (1863-83), oil on canvas, 87.9 x 150.1 cm, Walters Art Museum, Baltimore, MD. Wikimedia Commons.

We are back in the Circus Maximus, with the Palatine Hill in the background, although critics have claimed that this looks more like the Colosseum with the Acropolis of Athens behind. The sand in the arena is rutted with the tracks from earlier chariot races. There are nine crucifixes planted at regular intervals around the periphery of the arena; on each, a Christian has been coated with pitch and set alight.

Towards the right, a group of 40-50 Christian men, women and children are kneeling on the ground, listening to and praying with an elder, who is standing and talking as he looks up to the heavens. To the left, a trapdoor in the arena floor is open and a succession of wild animals are emerging into the arena. A large lion is first out and is already heading for the group of people. Still making their way up are a tiger and another lion.

One other figure is visible, at the left edge: the person who presumably controls the trapdoor, whose head and shoulders stand clear of a heavy stone wall.

Given Gérôme’s earlier efforts to be as historically accurate as possible, this painting is a disappointment. Such martyrdoms by wild beasts and crucifixion didn’t take place in the Circus Maximus. Given the artist’s record of narrative painting, it’s also strange that he should make the figures so distant, and the spectators so remote. As a result, this painting has none of the spectacle, drama, or widescreen effect of his earlier arena scenes. What should have been compelling drama is static and distant.

For his next conventional narrative painting, Gérôme turned to the Old Testament, and a story about King David and the corruption brought by power.

The Biblical story of Bathsheba is one of the more sordid of its histories. King David lusted after Bathsheba, a gentlewoman of fine birth who was married to one of the king’s generals. Having made her pregnant adulterously, David first tried to make it appear that the unborn child had been conceived in wedlock; when that failed he deliberately put her husband into danger in battle so he was killed, and David became able to marry her as a widow.

Jean-Léon Gérôme (1824–1904), Bathsheba (1889), oil on canvas, 60.5 x 100 cm, Private collection. Wikimedia Commons.

David first developed his lust for Bathsheba when he saw her bathing on the roof of her house, already a popular motif for paintings, and that chosen by Gérôme for his Bathsheba (1889).

Here is Bathsheba, washing herself, naked in the small garden on her roof. She has her back turned to the viewer, and is washing her left elbow with her right hand. Watching her intently from a balcony up to the left is the figure of David, leaning forward to get as close a look as he can, although it isn’t clear whether he has made eye contact with her. A servant is by Bathsheba’s feet, helping her bathe. Bathsheba’s clothes are piled loosely to her right, on a small stool. Behind them stretches the city, bathed in warm light. This motif seems to have evolved from several rooftop views among his Orientalist paintings, rather than any historical or personal event.

From the mid-1870s, Gérôme had also been a sculptor, specialising in polychromed marble figures. This led him to paint about sculpture, and to think about visual revelation and truth.

Jean-Léon Gérôme (1824–1904), The End of the Pose (1886), oil on canvas, 48.3 x 40.6 cm, Private collection. Wikimedia Commons.

The End of the Pose (1886) is the first of his series of unusual compound paintings, which are at once self-portraits of Gérôme as a sculptor, studies in the relationship between a model and their sculpted double, and further forays into issues of what is seen, visual revelation, and truth.

Here, while Gérôme cleans up, his model is seen covering up her sculpted double with sheets, as she remains naked. Apart from various diversionary entertainments, including a couple of stuffed birds and a model boat, there is a single red rose on the wooden platform on which the model and statue stand. Presumably this is a symbol of thanks from the artist to his model.

It isn’t far from here to the myth of the perfect sculptor Pygmalion, whose creation was given life, turning statue into lover, which was Gérôme’s next step in 1890.

Jean-Léon Gérôme (1824–1904), Pygmalion and Galatea (study) (1890), oil on canvas, 94 x 74 cm, Private collection. Wikimedia Commons.

This study for Pygmalion and Galatea from 1890 was an early attempt at the composition, with Pygmalion’s future bride still a marble statue at her feet, but very much flesh and blood from the waist up. That visual device was perfect, but Gérôme recognised that his painting would be shunned because of its full-frontal nudity, so he reversed the view.

Jean-Léon Gérôme (1824–1904), Pygmalion and Galatea (c 1890), oil on canvas, 88.9 x 68.6 cm, Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, NY. Wikimedia Commons.

Gérôme’s finished Pygmalion and Galatea (c 1890) extends the marble effect a little higher, and by showing Galatea’s buttocks and back and concealing the kiss, it stayed on the right side of what was deemed decent. His attention to detail is, as always, delightful, with two masks against the wall at the right, Cupid ready with his bow and arrow, an Aegis bearing the head of Medusa, and a couple of statues about looking and seeing.

Jean-Léon Gérôme (1824–1904), The Conspirators (1892), oil on canvas, 66 x 91.4 cm, Private collection. The Athenaeum.

The Conspirators from 1892 is another of Gérôme’s lesser-known paintings, and it isn’t clear how he chose this motif. There had certainly been no shortage of political conspiracies in France at this time, and in 1892 the Panama Canal Scandal was often in the headlines, and may have been the germ of inspiration.

Three men are in a huddle around a table at one end of an otherwise almost empty room. Lit by an unseen lamp between them, they’re discussing something highly secret. One hat hangs high on the wall at the right, and some other clothes are visible on a long bench running along the facing wall. There’s another, empty chair in the middle of the room.

In the final decade of his career, as he watched his popularity decline, Gérôme was to think, paint and write more about seeing the truth.

During the later years of his career he devoted much attention to the rising Impressionists, whom he vehemently opposed, sculpture, photography as an art, and the depiction of truth.

For someone who had devoted his career to the exercise of the high craft of painting in oils, and who had taught it to so many students, I think that Gérôme considered the Impressionists were neither painting ‘the truth’, nor telling ‘the truth’. He knew that their works, now selling well and becoming as valued by the market as his own, were neither faithful representations of what the artists saw, nor spontaneous ‘impressions’ dashed off at the height of sensory experience.

Gérôme’s painting fed his sculpture, and he painted his sculpture both literally (many of his works are in polychromed marble) and on canvas. He was also an early and enthusiastic photographer, who helped establish photography as a fine art at a time when most painters were hoping that it would just go away and leave their business alone. Together with his former pupils Jules-Alexis Muenier and Pascal Dagnan-Bouveret he used photography in his painting, and as an art in its own right.

Jean-Léon Gérôme (1824–1904), Sculpturae Vitam Insufflat Pictura (Painting Breathes Life into Sculpture) (1893), oil on canvas, 50.2 x 69.2 cm, Art Gallery of Ontario, Toronto. Wikimedia Commons.

In 1874, archaeologists had discovered large numbers of polychromed cast terracotta figurines in the Boeotian town of Tanagra. These dated from Greek civilisations active there during the late fourth century BCE, and their quantity and quality impressed many, including Gérôme.

Having painted the story of Pygmalion and Galatea in 1890, Gérôme moved on to two works in which he built imaginary worlds around the Tanagra figurines. Sculpturae Vitam Insufflat Pictura (Painting Breathes Life into Sculpture) (1893) combines his own love of polychrome sculpture with a celebration of those archaeological discoveries. In doing so, Gérôme progresses his long-running theme of visual revelation and truth, with these painted miniature humans, mimicking reality, and the wooden box of masks in the foreground. Several of the figurines refer to his own painting and sculpture.

Jean-Léon Gérôme (1824–1904), Atelier of Tanagra (1893), oil on canvas, 65.1 x 91.1 cm, Private collection. Wikimedia Commons.

As a painting, I don’t think that his Atelier of Tanagra (1893) is as effective and convincing as the previous work, but its wider range of figurines gives deeper insight into what Gérôme was thinking about. Several of the figurines shown here are his own polychrome sculptures, most obviously that of the naked woman sitting on the top of a blue pillar, in the centreline of the painting.

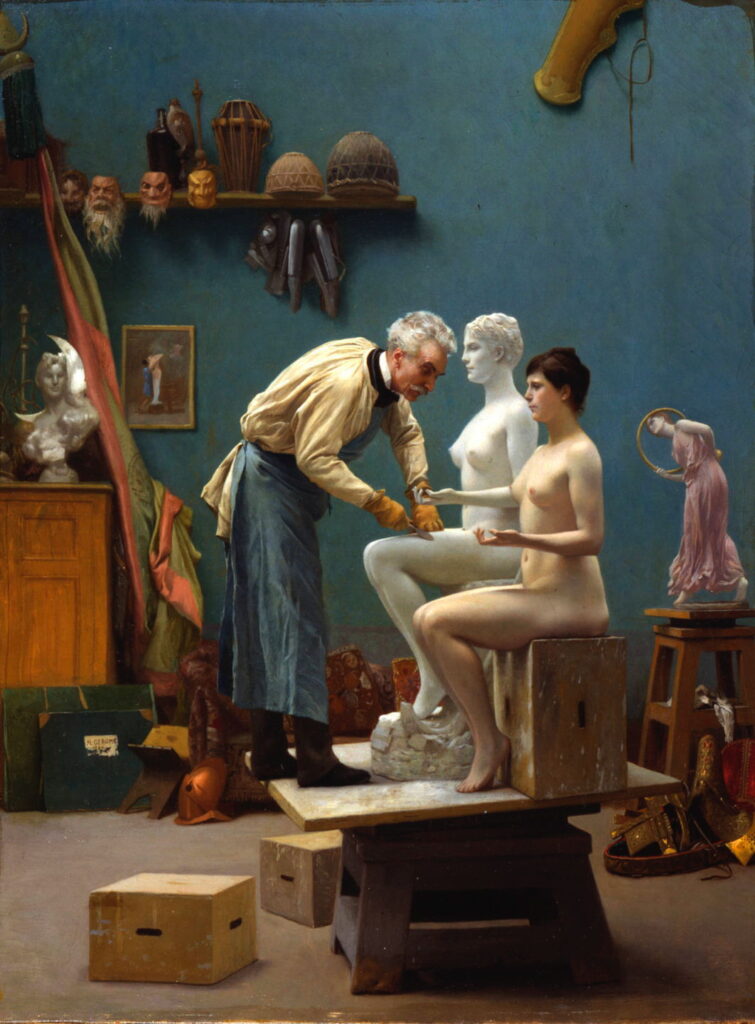

Jean-Léon Gérôme (1824–1904), The Artist’s Model (1895), oil on canvas, 50.8 x 39.6 cm, Dahesh Museum of Art, New York, NY. Wikimedia Commons.

In The Artist’s Model (1895), Gérôme paints himself at work on his marble figure Tanagra (1890), currently in the Musée d’Orsay, already included among the figurines in his Sculpturae Vitam Insufflat Pictura. He thus painted himself making a sculpture which he had previously painted in a painting as a sculpture. Not only that, but his model is his favourite Emma Dupont, who over a period of twenty years posed for many of his best-known Orientalist and other works.

Scattered in the image are reminders of gladiatorial armour and other props used for his paintings, one of his paintings of Pygmalion and Galatea, together with one of his polychrome sculptures of a woman with a hoop, at the right edge. In this single image, Gérôme has captured much of his professional career.

References

Ackerman GM (2000) Jean-Léon Gérôme, Monographie révisée, Catalogue Raisonné Mis à Jour, (in French) ACR Édition. ISBN 978 2 867 70137 5.

Scott Allan and Mary Morton, eds. (2010) Reconsidering Gérôme, Getty. ISBN 978 1 6060 6038 4.

Gülru Çakmak (2017) Jean-Léon Gérôme and the Crisis of History Painting in the 1850s, Liverpool UP. ISBN 978 1 78694 067 4.

de Cars L et al. (2010) The Spectacular Art of Jean-Léon Gérôme (1824-1904), Skira. ISBN 978 8 85 720702 5.