Changing Paintings: 21 The fate of Phineus, and the Muses on Helicon

Ovid starts the fifth book of his Metamorphoses at the wedding feast of Perseus and Andromeda, just after the groom has made the greatest wedding speech of all time, describing how he beheaded Medusa the Gorgon.

It’s at this point that the wedding feast gets out of hand, when his in-laws palace is invaded by a mob. Its ringleader is Phineus, King Cepheus’ brother, wielding a spear, who quickly establishes that, as far as he and his rabble are concerned, Perseus has stolen his bride, who also happens to be his niece. With a quick dig at Perseus’ conception by Danae with Jupiter’s ‘shower of gold’, Phineus argues with the king.

Phineus then hurls his spear at Perseus, only to embed it in the furniture. Perseus throws it back, but Phineus has ducked behind cover, and it kills someone else. This is the cue for open warfare, which in turn prompts Minerva to appear to guard Perseus with her shield. Ovid details a succession of violent deaths, in the course of which Perseus holds his own and remains unscathed. With his bride and mother-in-law screaming for all they’re worth, the hall is awash with blood, and corpses are starting to stack up on the floor. Perseus realises that he is seriously outnumbered, so holds up the head of Medusa.

One by one, Perseus’ adversaries are transformed into stone. Only one of those defending him is caught out, but Phineus somehow manages to avoid looking at Medusa’s face. Phineus then tries to excuse his conduct, claiming that he was only doing it for Andromeda. Perseus isn’t swayed, and struggling not to look at Medusa’s deadly face, Phineus swiftly joins the group of statues.

Annibale Carracci (1560-1609) and Domenichino (Domenico Zampieri) (1581-1641), Perseus and Phineas (1604-06), fresco, dimensions not known, Palazzo Farnese, Rome. Wikimedia Commons.

Annibale Carracci and Domenichino combined their talents in painting this fresco of Perseus and Phineas (1604-06) in the Palazzo Farnese in Rome. As Perseus stands in the centre brandishing Medusa’s face towards his attackers, Andromeda and her parents shelter behind, shielding their eyes for safety.

Luca Giordano (1632–1705), Perseus Turning Phineus and his Followers to Stone (c 1683), oil on canvas, 285 x 366 cm, The National Gallery (Bought, 1983), London. Courtesy of and © The National Gallery, London.

In Luca Giordano’s Perseus Turning Phineus and his Followers to Stone (c 1683), the process of petrification is made less obvious, but the carnage and mayhem better-developed.

Sebastiano Ricci (1659–1734), Perseus Confronting Phineus with the Head of Medusa (c 1705-10), oil on canvas, 64.1 × 77.2 cm, The J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles, CA. Courtesy of J. Paul Getty Museum.

Sebastiano Ricci’s Perseus Confronting Phineus with the Head of Medusa (c 1705-10) also shows the final moments of the battle, as Phineus cowers next to two of his henchmen who have almost completed the process of changing into stone.

Jean-Marc Nattier (1685–1766), Perseus, Under the Protection of Minerva, Turns Phineus to Stone by Brandishing the Head of Medusa (date not known), oil on canvas, 113.5 × 146 cm, Musée des Beaux-Arts de Tours, Tours, France. Wikimedia Commons.

Surprisingly, none of those paintings made any clear reference to Minerva’s protection of Perseus, which is clearly expressed in Jean-Marc Nattier’s undated painting of Perseus, Under the Protection of Minerva, Turns Phineus to Stone by Brandishing the Head of Medusa. The goddess, Perseus’ half-sister, is sat on a cloud to the right of and behind the hero. She wears her distinctive helmet, grips her spear, and her left hand holds her Aegis bearing the image of Medusa’s face. Perseus points his weapons away from himself and Minerva, and is looking up towards the goddess. In the foreground, one of Phineus’ party seems to be sorting through the silverware, perhaps intending to make off with it.

Perseus and Andromeda leave the palace filled with dozens of statues and return to Argos. There they find that Proetus has usurped power. He too feels the awesome power of Medusa’s gaze, as does another old enemy, Polydectes King of Seriphos.

When Minerva leaves Perseus and Andromeda there, she heads straight for Helicon, the mountain abode of the nine Muses. The goddess has heard that Pegasus, the flying horse born from the blood of Medusa, has brought forth a new spring on Helicon, arising from his hoof-print.

Urania, Muse of astronomy, welcomes Minerva and confirms the story about the new spring and its novel origin. One of the Muses then raises concern for their safety, telling the story of Pyreneus who had tried to imprison them in his house. Fortunately for them, he then leapt from the high tower of that house, and smashed his skull.

The goddess is next distracted by the voices of the nine daughters of Pierus, the Pierides, known for being so puffed up with pride that they travelled around challenging others to sing tales. The Pierides now challenge the Muses, telling false stories of the Titans and belittling the gods, including claims that the gods had taken refuge in the form of animals.

Joos de Momper (1564–1635), Helicon or Minerva’s Visit to the Muses (c 1610), oil on panel, 140 x 199 cm, Koninklijk Museum voor Schone Kunsten Antwerpen, Antwerp, Belgium. Wikimedia Commons.

Joos de Momper’s splendid Helicon or Minerva’s Visit to the Muses (c 1610) is one of the most complete accounts to be firmly rooted in Ovid’s Metamorphoses.

Pegasus, perhaps a little smaller than expected, rears on his wings at the top of the new spring cascading down a small cliff at the right. Minerva is at the left, suitably helmeted, holding her spear in her left hand, and with her shield bearing the image of Medusa’s head. Between them are the Muses, each busily exercising their arts, with a mischievous putto fiddling at the back of the organ. Wheeling above the rugged landscape of Helicon are slightly more than nine birds, some bearing the distinctive black and white markings of magpies, representing the Pierides after their forthcoming transformation.

Jacques Stella (1596–1657), Minerva and the Muses (c 1640-45), oil on canvas, 116 x 162 cm, Musée du Louvre, Paris. Wikimedia Commons.

Jacques Stella’s Minerva and the Muses (c 1640-45) is a slightly later, but almost as complete, account. We’re higher up the slopes of Helicon, and in the distance on the left is Pegasus, being mobbed by putti. Minerva is on the right, armed with her spear and Aegis-shield. Several of the nine Muses are accompanied by appropriate attributes, and two are engaged in conversation with Minerva. There’s no sign of the Pierides, though.

Hendrick van Balen (1573–1632), Minerva and the Nine Muses (c 1610), oil on panel, 78 x 108 cm, Private collection. Wikimedia Commons.

Hendrick van Balen’s Minerva and the Nine Muses (c 1610) also shows all the key figures. The nine Muses are seated, forming a small orchestra with their contemporary rather than classical instruments. Minerva, at the left, is being engaged by a tenth woman, whose identity isn’t clear. In the far distance, just beyond a waterfall (the new spring), Pegasus is about to take off from a high cliff. Above, there are two magpies, implying the imminent arrival of the Pierides.

By the mid-1600s, these stories seem to have largely faded from the canvas. Occasional works appeared, from Richard van Orley in 1732, and Jean Pierre Norblin de la Gourdaine in 1830. Then in 1886, Gustave Moreau started to paint The Pierides, which he sadly never completed.

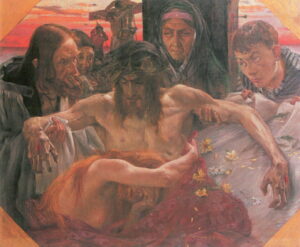

Gustave Moreau (1826–1898), The Pierides (1886-89), oil on canvas, 150 × 95 cm, location not known. Wikimedia Commons.

What we see of his work in progress is something of a puzzle, as a result of the confusion of names (hardly of Moreau’s doing). For in later classical times, the Muses also became known as the Pierides, so Moreau’s title could refer to either the Muses themselves, or their failed rivals. This confusion arose because the Muses, the daughters of Mnemosyne and Jupiter, were born in Pieria, near Mount Olympus, and were sometimes referred to as being Pierians.

In any case, there are at least fifteen figures in this painting, although some are in groups of three, and some are winged. It seems most probable that the black-winged figures are intended to be the daughters of Pierus, turned into magpies and fleeing the triumphant Muses.

After the Pierides had finished, the Muses sing their tales. They offer to repeat them for Minerva, who accepts, and sits herself down for the next, and much longer, story.