Reading visual art: 134 Flags A

Flags and standards probably originated with land battles, where they have been used extensively for identification. Even before battle is joined, working out which battalion is whose can be difficult. Rallying your men under their standard and leading them in to fight has been basic practice for centuries, even millennia. Flags and pennants also became popular on sailing vessels, and have been standardised into flag codes used to communicate between ships both in war and at peace.

This article shows some examples of flags in paintings, starting with their roles in narratives, and tomorrow’s article concludes with the part they play in national identity, a more recent phenomenon.

Joseph Mallord William Turner (1775–1851), Ulysses Deriding Polyphemus (1829), oil on canvas, 132.7 × 203 cm, The National Gallery, London. Wikimedia Commons.

JMW Turner’s Ulysses Deriding Polyphemus (1829) is faithful to Homer’s account of his hero leaving the blinded cyclops in the Odyssey, although the distant form of Polyphemus is hard to discern high on the top of the cliffs towards the left. He shows the entire crew led by Odysseus brandishing two large flags, arrayed up the masts and rigging to deride the blinded giant. The orange flag on the mainmast (detail below) bears the Greek word Οὖτις (Outis), the name that Ulysses claimed was his.

Joseph Mallord William Turner (1775–1851), Ulysses Deriding Polyphemus (detail) (1829), oil on canvas, 132.7 × 203 cm, The National Gallery, London. Wikimedia Commons.

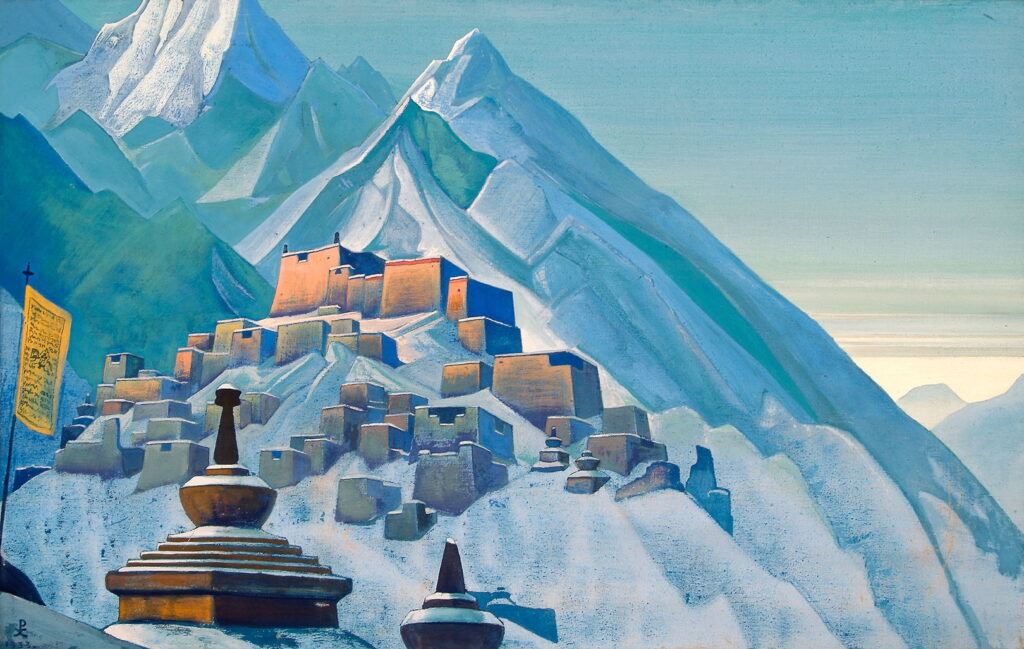

Nicholas Roerich (1874–1947), Tibet, Himalayas (1933), tempera on canvas, 74 x 117 cm, location not known. Wikimedia Commons.

Nicholas Roerich’s painting of Tibet, Himalayas from 1933 is one of few showing a Buddhist monastery high in the mountains, with a prayer flag at the left.

Flags and standards are popular devices in chivalry.

Johann Friedrich Overbeck (1789-1869), The Archangel Gabriel Appears to Godfrey of Bouillon (1819-27), fresco, dimensions not known, Casa Massimo, Rome, Italy. Image by Sailko, via Wikimedia Commons.

In this section of Johann Friedrich Overbeck’s magnificent frescoes of Tasso’s Jerusalem Delivered in the Casa Massimo in Rome, The Archangel Gabriel Appears to Godfrey of Bouillon. His companions are still asleep as Gabriel speaks to Godfrey, clutching what most would now recognise as a flag of the Cross of Saint George, in red on a white background.

Edmund Blair Leighton (1852–1922), The Accolade (1901), oil on canvas, 182.3 x 108 cm, Private collection. Wikimedia Commons.

Much later, the chivalric paintings of Edmund Blair Leighton feature standards. The Accolade from 1901 apparently shows Henry VI the Good – of Poland, not the British Henry VI – being dubbed a knight, with a standard held high in the background.

Edmund Blair Leighton (1852–1922), Stitching the Standard (1911), oil on canvas, 98 × 44 cm, Private collection. Wikimedia Commons.

In Leighton’s Stitching the Standard from 1911, a young princess sits in a cutout at the top of a castle wall, sewing the black and gold flag to be flown from the castle. She comes straight from Arthurian legend, or a fairy tale, perhaps.

During the Renaissance and shortly after, standards became common in paintings of the Passion, to signify the involvement of Pontius Pilate and the Roman Empire.

Raphael (1483–1520), Christ Carrying the Cross (Lo Spasimo di Sicilia) (c 1516), oil on wood transferred to canvas, 318 x 229 cm, Museo Nacional del Prado, Madrid, Spain. Wikimedia Commons.

Raphael’s Christ Carrying the Cross from about 1516 is an unusual treatment of this popular subject, as he uses an upright or ‘portrait’ orientation. As Christ struggles under the burden of his cross, he is comforted by the group of women at the right; the muscular man behind Christ and the cross is Joseph of Arimathaea, who is energetically lifting the load from Christ’s shoulder. There’s a wealth of fine detail in the other figures, stretching deep towards Calvary in the distance, and the letters SPQR appear reversed on the large red flag at the upper left.

Jacopo Tintoretto (c 1518-1594), The Crucifixion (E&I 123) (1565), oil on canvas, 536 x 1224 cm, Albergo, Scuola Grande di San Rocco, Venice, Italy. Wikimedia Commons.

Jacopo Tintoretto’s vast Crucifixion painted in 1565 for the Scuola Grande di San Rocco in Venice features a similar flag in the left distance, as shown in the detail below.

Jacopo Tintoretto (c 1518-1594), The Crucifixion (detail) (E&I 123) (1565), oil on canvas, 536 x 1224 cm, Albergo, Scuola Grande di San Rocco, Venice, Italy. Wikimedia Commons.

Jacopo Tintoretto (c 1518-1594), Ascent to Calvary (E&I 128) (1566-67), oil on canvas, 285 x 400 cm, Albergo, Scuola Grande di San Rocco, Venice, Italy. Image by Sailko, via Wikimedia Commons.

Tintoretto’s companion painting of the Ascent to Calvary is unusual among paintings of this phase of the Passion for its inclusion of all three of those to be crucified bearing their crosses. Christ is naturally prominent in the upper half of a composition dominated by diagonals, formed by the winding path and the crosses themselves. In the upper distance are banners declaring the oversight of the Roman authorities, in their inscriptions of SPQR.

Flags don’t have to be large or prominent to play significant roles in paintings, as demonstrated in Caspar David Friedrich’s masterpiece generally known as The Stages of Life, painted in 1834-35.

Caspar David Friedrich (1774–1840), Die Lebensstufen (Strandbild, Strandszene in Wiek) (The Stages of Life) (1834-5), oil on canvas, 72.5 x 94 cm, Museum der bildenden Künste, Leipzig. Wikimedia Commons.

This shows five figures and assorted fishing equipment at the water’s edge, with five vessels sailing behind them. Two of the figures are children, who raise a small Swedish flag between them, as a reminder of Friedrich’s origins in Swedish Pomerania (detail below). To their right is a young woman, pointing and looking towards the children. To their left is a mature man, wearing a top hat, who is turned towards an elderly man, the closest to the viewer, his back towards us and a walking stick in his right hand. The younger man is gesticulating, his right hand towards the old man, his left pointing down towards the children.

Caspar David Friedrich (1774–1840), Die Lebensstufen (Strandbild, Strandszene in Wiek) (The Stages of Life) (detail) (1834-5), oil on canvas, 72.5 x 94 cm, Museum der bildenden Künste, Leipzig. Wikimedia Commons.