Lovis Corinth and Charlotte Berend: 2 Recovering from disaster

In December 1911, when he was 53 and at the peak of his career, Lovis Corinth suffered a major stroke. At first his doctors weren’t even confident that he would survive, and when he did regain consciousness, he couldn’t recognise his wife Charlotte. His left arm and leg were completely paralysed; as he had painted his entire professional career with his left hand, it looked as if that career was over.

Over the following weeks he made a rapid recovery. His left arm remained weak for some time, and he needed a stick when walking, but by February 1912 he had completed his first self-portrait since his stroke, and was painting actively once again, thanks largely to the support of Charlotte.

Corinth’s paintings changed visibly after his stroke. There’s controversy among commentators as to how much of this change was the result of its effects, and how much his launch into Expressionist style was intentional. Another question is whether any residual weakness or impaired hand-eye co-ordination may have brought other changes to his technique. Did he, for example, have to learn to paint using his right hand as compensation?

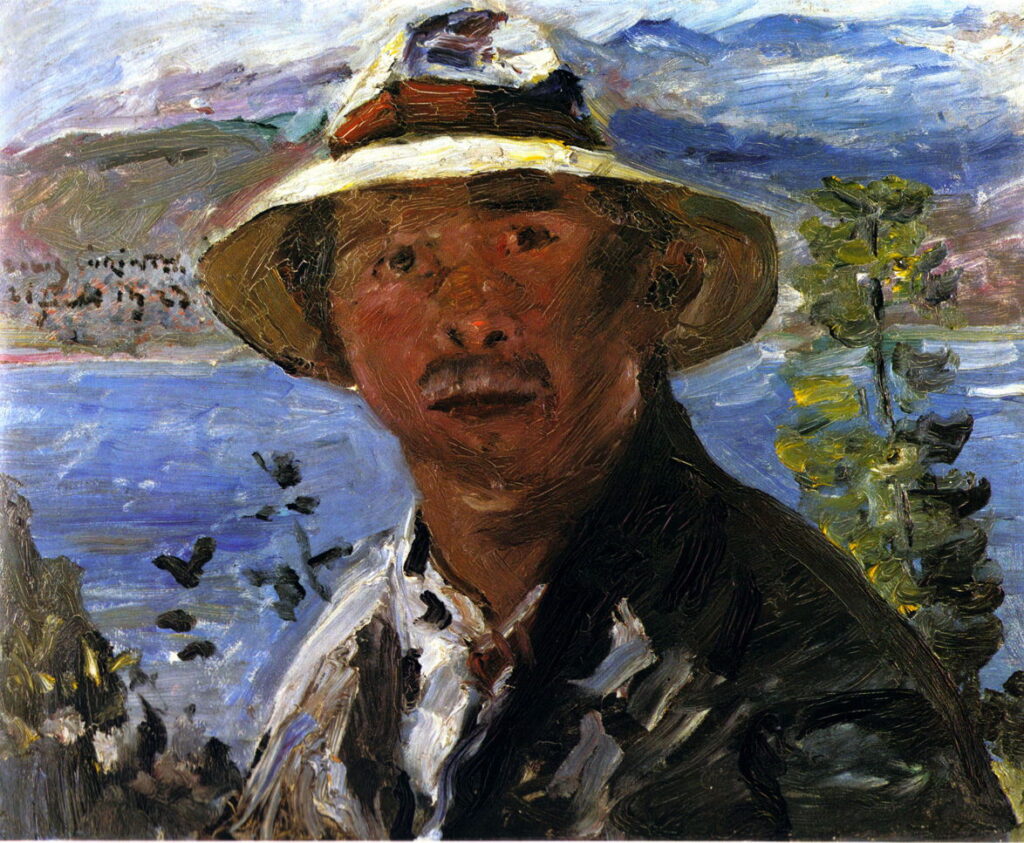

Lovis Corinth (1858–1925), Self-portrait with a Panama Hat (1912), oil on canvas, 66 × 52 cm, Kunstmuseum Luzern, Lucerne, Switzerland. Wikimedia Commons.

He painted this Self-portrait with a Panama Hat during his recovery in 1912, and it differs little in its facture from earlier work. His facial expression and bearing have changed totally, though, his eyes staring through the struggle that he has had, in concerned contemplation.

Once Corinth was fit enough after his stroke, he travelled with Charlotte for three months of convalescence on the French Riviera at Bordighera.

Lovis Corinth (1858–1925), Balcony Scene in Bordighera (1912), oil on canvas, 83.5 × 105 cm, Museum Folkwang, Essen, Germany. Wikimedia Commons.

Balcony Scene in Bordighera (1912) shows Charlotte with a miniature parasol to shelter her from the dazzling sun, on the balcony of their accommodation. His rough facture has extended more generally now from his nudes and sketches, marking his move from more Impressionist landscapes to Expressionism.

There are also interesting traits in his brushwork at least partly reflecting his recovering stroke. Verticals, indeed the whole painting, tend to lean to the left, in opposition to the diagonal strokes used to form the sky, more typical of someone painting with their right hand. His previously rigorous perspective projection has been largely lost, although he maintains an approximate vanishing point at the right of the base of Charlotte’s neck. He has employed aerial perspective, but the painting lacks the effect of depth seen in his earlier work.

Lovis Corinth (1858–1925) Italian Woman with Yellow Chair (1912), oil on canvas, 90.5 x 70.5 cm, Niedersächsisches Landesmuseum Hannover, Hanover. Wikimedia Commons.

During this recovery period, he painted an Italian Woman in a Yellow Chair (1912). There has been speculation as to whether this wasn’t a local Italian model at all, but Charlotte. The hat does seem to have been his wife’s, and appears in a sketch of her made at about the same time.

Lovis Corinth (1858–1925), Storm off Cape Ampelio (1912), oil on canvas, 49 × 61 cm, Staatliche Kunstsammlungen, Gemäldegalerie Neue Meister, Dresden. Wikimedia Commons.

Storm off Cape Ampelio (1912) shows rough seas at the cape near to Bordighera. Its brushwork has great vigour, and captures the violent surges which occur when incident and reflected waves meet. Again its verticals are leaning to the left.

Lovis Corinth (1858–1925), The Blinded Samson (1912), oil on canvas, 105 x 130 cm, Alte Nationalgalerie, Berlin. Wikimedia Commons.

His first major painting following his stroke returned to his earlier theme of Samson. This autobiographical portrait of The Blinded Samson (1912) expressed his feelings about his own battle against the sequelae of his stroke.

In the Samson story, it shows the once-mighty man reduced to a feeble prisoner, forced to grope his way around. No doubt Corinth didn’t intend referring to its conclusion: with the aid of God, he pulled down the two central columns of the Philistines’ temple to Dagon, and brought the whole building down on top of its occupants.

Although still rough in its facture, Corinth has now restored his verticals and clearly got the better of any residual mechanical problems in his painting.

Lovis Corinth (1858–1925), At the Mirror (1912), oil on canvas, dimensions not known, Worcester Art Museum, Worcester, MA. Wikimedia Commons.

At the Mirror (1912) is an ingenious painting using the woman’s reflection to make clear the struggle that Corinth, here seen only in reflection, had gone through to paint his images. Instead of providing the viewer with a faithful and detailed reflection, that image is even more loosely painted, rendering her face, and Corinth’s, barely recognisable.

Lovis Corinth (1858–1925), View of the Jetties in Hamburg (1912), oil, dimensions not known, Museum Georg Schäfer, Schweinfurt, Bavaria. Image by Tilman2007, via Wikimedia Commons.

View of the Jetties in Hamburg (1912) shows the continuing looseness of his facture. Its verticals are more consistent and vertical than in his paintings in Bordighera, and his brushstrokes are varied in orientation.

In the first year since his stroke, Corinth’s painting had come a long way. What he must have feared would turn out be career-ending was not. The event may have accelerated his move to Expressionist style, but it doesn’t seem to have driven or determined it.

Lovis Corinth (1858–1925), Self-portrait with Tyrolean Hat (1913), oil on canvas, 80 × 60 cm, Museum Ludwig, Cologne. Wikimedia Commons.

By 1913, in his Self-portrait with Tyrolean Hat, he appears to be on holiday in the South Tyrol, marked by his headgear and the inscription at the right. His face has become more gaunt and worried. Although he appears to be holding his brush in his right hand, it’s actually clasping several brushes and his palette, indicating he was painting with the left.

Lovis Corinth (1858–1925) Ariadne on Naxos (1913), oil on canvas, 116 × 147 cm, Private collection. Wikimedia Commons.

Ariadne on Naxos is one of Corinth’s most sophisticated mythical paintings, and was inspired by the first version of Richard Strauss’s opera Ariadne auf Naxos (1912). This was first performed in Stuttgart in October 1912, and Corinth probably attended its Munich premiere on 30 January 1913. Wikipedia’s masterly single-sentence summary of the opera reads: “Bringing together slapstick comedy and consummately beautiful music, the opera’s theme is the competition between high and low art for the public’s attention.”

Lovis Corinth (1858–1925), Portrait of Charlotte Berend-Corinth (1915), oil on canvas, 54.5 × 40.5 cm, location not known. Wikimedia Commons.

But both Corinth and his wife were growing older, and more tired. Portrait of Charlotte Berend-Corinth (1915) shows a very different woman from that of just a few years earlier, with her brow knitted and her joyous smile gone.

Corinth celebrated his sixtieth birthday in 1918, and was made a professor in the Academy of Arts of Berlin. However, with the end of the war and its unprecedented carnage, disaster for Germany, and the revolution, he slid into depression.

In the summer of 1918, Corinth and his family had first visited Urfeld, on the shore of Walchensee (Lake Walchen), to the south of Munich. They fell in love with the countryside there, and the following year bought some land on which Charlotte arranged for a simple chalet to be built. In the coming years, the Walchensee was to prove Corinth’s salvation, and the motif for at least sixty superb landscape paintings.

Lovis Corinth (1858–1925), Self-portrait in a Straw Hat (1923), cardboard, 70 x 85 cm, Kunstmuseum Bern, Switzerland. Wikimedia Commons.

During this period of frenetic painting, he at first appeared to flourish in the sunshine and fresh air. His Self-portrait in a Straw Hat from 1923 shows him looking in rude health.

Lovis Corinth (1858–1925), Last Self-Portrait (1925), oil on canvas, 80.5 × 60.5 cm, Kunsthaus Zürich, Zürich. Wikimedia Commons.

Corinth’s Last Self-Portrait, painted just two months before his death in 1925, is unusual in showing him with his reflection in a mirror. He’s now balding rapidly, his cheeks sunken, and his eyes are bloodshot and tired.

That summer he travelled to the Netherlands to view Old Masters, including Rembrandt and Frans Hals. He developed pneumonia, and died at Zandvoort on 17 July, four days before his sixty-eighth birthday. He had painted more than a thousand works in oil, and hundreds of watercolours. Ironically, it was the rise of the Nazi party from 1933 that prevented him from achieving the international recognition his work deserved.

His widow Charlotte had remained active in her art. In the 1920s she painted book illustrations and supported young artists from Berlin’s theatres. She even took part in the art competition at the 1932 Summer Olympics. In 1933 she emigrated to the USA, to join her son Thomas in New York City. She compiled her husband’s catalog raisoné, published in 1958, and died in 1967 at the age of 86. Because her death is relatively recent, I deeply regret that I’m unable to show any of her paintings, due to copyright restrictions.

References

Lemoine S et al. (2008) Lovis Corinth, Musée d’Orsay & RMN. ISBN 978 2 711 85400 4. (In French.)

Czymmek G et al. (2010) German Impressionist Landscape Painting, Liebermann-Corinth-Slevogt, Arnoldsche. ISBN 978 3 89790 321 0.