Where should you back up to?

Backing up is the most important of all housekeeping tasks, and can prove the most complicated. Until Apple introduced Time Machine in 2007, relatively few Mac users backed regularly, but this has thankfully changed since. This article explains the principles behind one key aspect of backing up: having decided that you’re going to back your Mac up, what should you back it up to?

What if?

The purpose of backing up is to ensure that all the documents and files you need are available to restore in the event that local copies are lost or damaged. That might occur in many different scenarios, ranging from human error trashing files or folders (most common), through failure of local storage or Mac, to complete disaster in which everything is destroyed and storage isn’t recoverable.

Think both the plausible and the unthinkable, and consider what backups you need to make to ensure that you can always retrieve copies of your important files. In each case, consider the fidelity of the copies that you’d restore from, speed of making backups, and the safe custody of your backups in each scenario.

Fidelity of backups

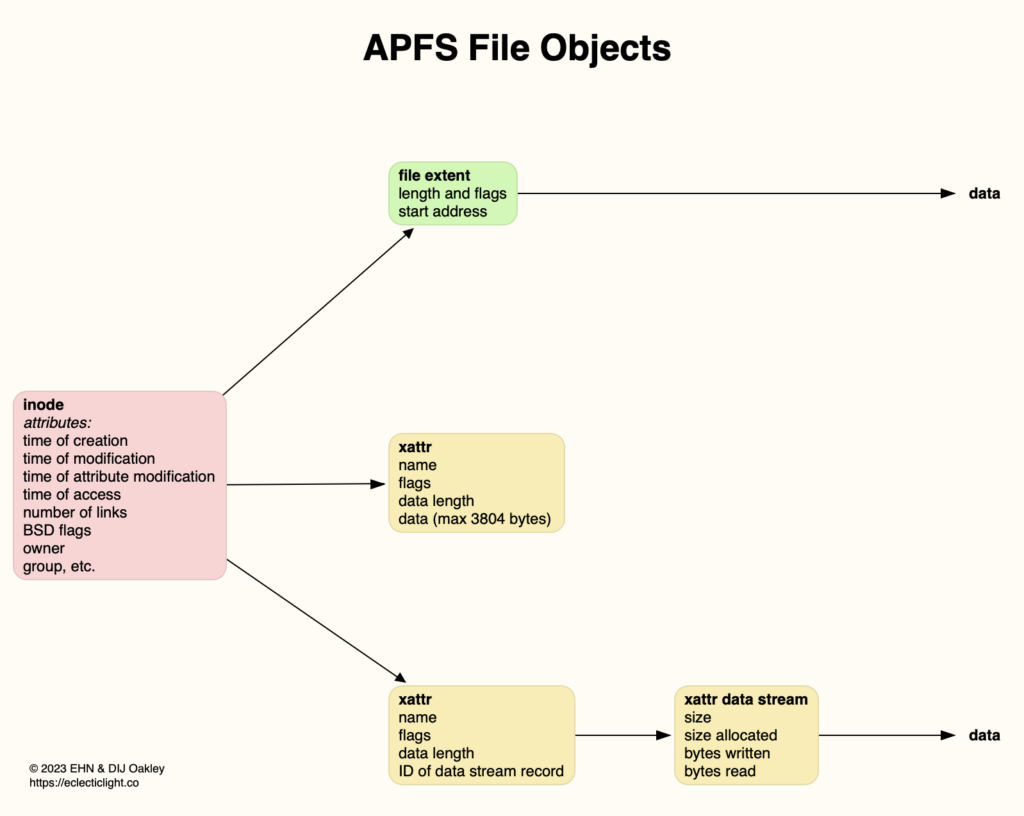

Fidelity is an important consideration, as Mac native files are more complex than in many file systems, because they consist of more than just the file’s attributes and its data.

Not only are Mac file attributes richer, but there are extended attributes, xattrs, that are often lost when a Mac file is transferred to another file system, other than APFS and HFS+.

APFS also supports three special file types:

Sparse files containing significant amounts of empty data; rather than store that empty data, when the file is written according to the rules, only non-empty data is stored. Although some other file systems have similar sparse formats, they aren’t interoperable and even copying an APFS sparse file will ‘explode’ it to full size. Originally, sparse files were unusual, but have become increasingly common, and disk images are often stored in sparse format.

Clone files in which some or all of the data are common to another file. These only operate within a single file system or volume, so are usually separated or uncloned when copied to another volume.

Dataless files whose data is stored elsewhere, typical in cloud storage. Their data has to be downloaded or materialised before the file can be backed up, a process that can take a significant amount of time.

The higher the fidelity of backup copies of files, the more limited the choice of file systems that can be used to store them.

Fidelity is one of the trade-offs in choosing where you back up to. Speed of connection to local storage is invariably highest; the more remote the storage is, the slower backup files can be written to it. However, the more remote the storage is from the Mac, the greater the chances of the backup surviving local catastrophes. A thorough backup plan should balance those across multiple backup storage to cover all the what ifs you’ve identified.

Local storage

Storage connected directly to a Mac is fastest, most likely to be high fidelity, and least safe from disaster.

Write speeds can approach the maximum of the Thunderbolt/USB4 bus connecting an SSD to the Mac, over 3 GB/s. In practice, that is seldom if ever achieved because of the overhead involved in copying. Fidelity depends on the file system used for the storage, but if that’s the same as the APFS source, true replicas should be expected, including most if not all xattrs, and preservation of sparse file format.

Efficiency is more variable: copying blocks of data rather than whole files avoids unnecessary duplication in the backup, and ensures both optimum speed and storage efficiency. It’s also an unusual feature in backup utilities; currently the only product that does consistently back up at a block level appears to be Time Machine, and even then only when backing up from APFS to APFS storage.

Network storage

Transferring files over a network requires the use of network file protocols, of which AFP and SMB have been the most widely used for network backups with macOS. AFP has been deprecated for some years, and is being phased out with newer Macs and more recent macOS. Wherever possible, SMB is preferred now.

Even when used between two Macs on a local network, Time Machine backs up to a sparse bundle on the backup storage, rather than directly to the local file system. The sparse bundle hosts a virtual file system, which in the past has been HFS+ but is now more appropriately APFS. The latter achieves high fidelity at the cost of increased complexity and slower transfers, but for many proves a good compromise.

Sparse bundles are used for this as they’re independent of file system, and consist of a folder contain a large number of ‘band’ files, which expand in size and increase in number as required to accommodate the files stored within them. Maximum band size is determined by the maximum capacity of the sparse bundle, and there are trade-offs between the number of bands and their management. As backups tend to grow in size and never shrink, maintenance requirements should be considerably less than would be expected for general purpose storage using sparse bundles.

Third-party backup utilities like Carbon Copy Cloner aren’t as dependent on the file system they back up to, although you should read their documentation carefully before deciding whether to use them to back up directly to a shared file system: for Carbon Copy Cloner, full details are given here.

Cloud storage

This presents the greatest challenges for fidelity, as few cloud storage systems can match the rich features of APFS as a local file system. Apple doesn’t currently recommend the use of iCloud Drive for backup storage for Macs, and it doesn’t appear to be particularly suitable even if you can achieve the bandwidth necessary to make this feasible. However, for those who don’t have any better option for off-site backups of critical documents, iCloud Drive can be invaluable.

Third-party cloud providers are unlikely to provide services that cope with anything more than file attributes and data, and typically exclude all xattrs. Software support becomes critical here, particularly if you need to restore substantial numbers of files from cloud storage, something that won’t normally be supported by standard macOS migration or restore procedures.

Remote physical storage

In the days before cloud backup, many small businesses maintained substantial off-site backups using spare disks from a RAID 1 mirror to keep one complete backup at another physical location. This requires a minimum of three disks for a two-disk mirror. At the end of each day, the existing RAID pair is broken by removing one of the disks, which is then taken off-site as the backup. The other disk is then inserted into the RAID array, which rebuilds the mirrored pair overnight, ready to take fresh backups the following morning. That and similar practices can still be used today.

Recommendations

Establish your what ifs.

For each level of backup, consider fidelity, speed and safety.

Local backups to APFS are most faithful, fastest, and highest risk.

Network backups may be less faithful, are slower, and lower risk.

Cloud backups are least faithful, slowest, and should be at lowest risk.

Remote physical storage can be high fidelity, is usually slow, and lower risk.

Use multiple backup stores to cover all your risks as required by the importance of your files.

Periodically test restoring from each of your backup stores. Don’t just assume that they will work when needed.