A painted weekend in Morocco: 1832-65

This weekend we’re off for a whirlwind visit to Morocco, thanks to the paintings of a succession of masters from France, Spain and the USA.

Morocco, on the north-west coast of Africa, is actually to the west of France and most of the rest of Western Europe, yet it was one of the birthplaces of Orientalist painting. Although there had been a much longer interest in painting the Middle East, artists didn’t start frequenting North Africa until the early nineteenth century, when Eugène Delacroix became one of the first pioneers.

In the summer of 1830, the French King Louis-Philippe’s army had taken Algiers, to the east, and he became keen to extend French influence in North Africa. By mid-October, Count Charles de Mornay had been appointed to lead a diplomatic mission to the chief sovereign of Morocco, and the Count’s wife had recommended that he took Delacroix with him as his artist, largely on the grounds of his social skills rather than his art.

Delacroix had little time to prepare, and at three o’clock in the morning of 1 January 1832, once they had completed their New Year celebrations, the Count and his artist set off for Toulon, from where they sailed on a frigate ten days later. They arrived off Tangier on the twenty-fourth, and he then spent the period until the tenth of May ashore in Morocco, which included Ramadan. During his return, Delacroix spent some time in Algiers, where he gained access to the interior of a Muslim home. At the end, Delacroix had filled at least seven sketchbooks and many loose sheets with watercolours, annotations and other material that he was to use during the rest of his career.

Eugène Delacroix (1798–1863), Three Arab Horsemen at an Encampment (c 1832), watercolour on wove paper, 21.7 x 29.6 cm, Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, NY. Wikimedia Commons.

Delacroix painted many watercolour views of Moroccans with their horses, including these Three Arab Horsemen at an Encampment.

Eugène Delacroix (1798–1863), Strolling Players (1833), watercolour, 24.8 x 18.4 cm, Los Angeles County Museum of Art, Los Angeles, CA. Wikimedia Commons.

His Strolling Players may have been painted the following year from his contemporary notes.

Delacroix’s burning desire was to see inside the home of a Muslim family, and to paint the visual riches that he expected to see there. During his stay in Morocco, the closest that he got was visiting several of the local Jewish community, and his notebooks contain annotated sketches and watercolour paintings of what he saw.

Eugène Delacroix (1798–1863), Arab Fantasy (1833), oil on canvas, 60.5 x 74.5 cm, Städelsches Kunstinstitut und Städtische Galerie, Frankfurt am Main, Germany. Wikimedia Commons.

This Arab Fantasy from 1833 is one of several he painted as he worked up his watercolours from North Africa.

Eugène Delacroix (1798–1863), Women of Algiers in their Apartment (1834), oil on canvas, 180 x 229 cm, Musée du Louvre, Paris. Wikimedia Commons.

Delacroix’s Women of Algiers in their Apartment is his first Orientalist masterpiece, based in part on the watercolours and sketches made of local models during his visits to Morocco and Tangier, combined with studio work in Paris using a European model dressed in clothing the artist had brought back from North Africa. The black servant at the right appears to be an invention added for effect, as an extra touch of exoticism. The end result is harmonious, and makes exceptional use of light and colour, its fine details giving the image the air of complete authenticity.

Eugène Delacroix (1798–1863), The Fanatics of Tangier (1837-38), oil on canvas, 95.5 x 128.5 cm, Minneapolis Institute of Art, Minneapolis, MN. Wikimedia Commons.

When in Tangier, Delacroix had encountered and sketched members of a Sufi brotherhood who converged on their founder’s monument in Meknès each August. Tucked away in the safety of an attic, the artist had produced a watercolour, since lost, and in 1837 started to paint his finished oil version of The Fanatics of Tangier (1837-38). It proved controversial when exhibited at the Salon in 1838, although some critics, and later Georges Seurat, considered his brushwork and colour caught the movement of the crowd admirably.

Delacroix had also been invited to attend a Jewish wedding held in Tangier, from which he painted several watercolour studies, culminating in another masterpiece.

Eugène Delacroix (1798–1863), Jewish Wedding in Morocco (1837-41), oil on canvas, 104 x 140 cm, Musée du Louvre, Paris. Wikimedia Commons.

Delacroix started to paint the Jewish Wedding in Morocco in 1837, apparently as a commission, and completed it in time for the 1841 Salon. The viewer is given the opportunity to see one of the women dancing in honour of the bride, in a ceremony clearly intended to be very private.

At the time his Orientalist paintings were rapidly rising in value, and the artist found the heir to the French throne, Ferdinand-Philippe, the Duke of Orléans, was willing to pay substantially more for the painting. The Duke quickly donated it to the Musée du Luxembourg, and it has since been transferred to the Louvre. In about 1875, Renoir made a faithful copy for the Delacroix collector and industrialist Jean Dollfus.

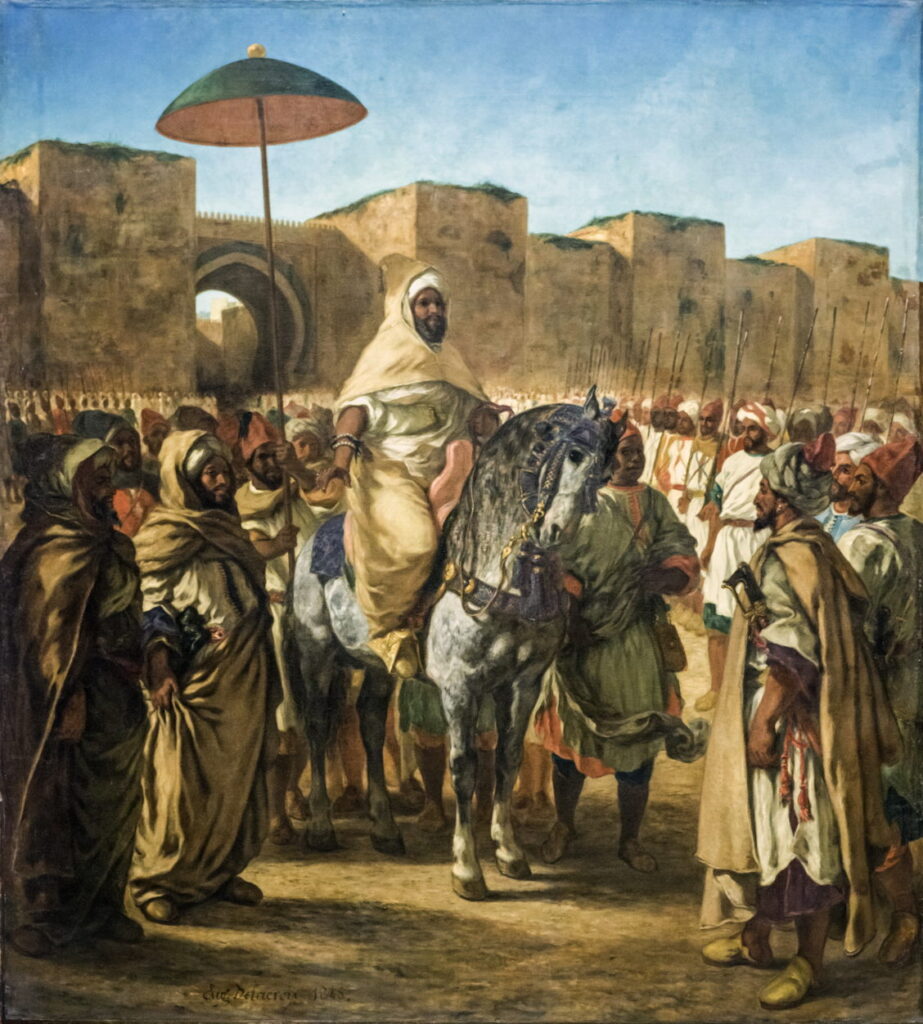

Eugène Delacroix (1798–1863), The Sultan of Morocco and His Entourage (1845), oil on canvas, 377 x 340 cm, Musée des Augustins de Toulouse, Toulouse, France. Image by Didier Descouens, via Wikimedia Commons.

Another large painting shown at a later Salon is also derived from his visit to Morocco a decade earlier. The Sultan of Morocco and His Entourage (1845) shows Moulay Abd-er-Rahman, Sultan of Morocco, leaving his palace in Meknès on 22 March 1832. This was based on a quick sketch in ink he made at the time, coupled with written notes, later developed through a series of studies. As with his other Orientalist paintings, it has rich and harmonious bursts of colour, and was justly acclaimed by the critics.

Eugène Delacroix (1798–1863), Arabs Skirmishing in the Mountains (1863), oil on canvas, 92.5 x 74.5 cm, National Gallery of Art, Washington, DC. Wikimedia Commons.

In one of his last oil paintings, Delacroix returned to Morocco for these Arabs Skirmishing in the Mountains (1863), which refers back to his Abduction of Rebecca from 1846 with its distant hilltop castle, and to his several depictions of Lord Byron’s poem The Giaour starting from 1826.

At the same time that Delacroix was painting that and his other final works, the Spanish artist Marià Fortuny was at the other end of his career. In early 1860 he had been sent as an official artist to the Spanish-Moroccan War. For three months he painted in the field, and returned with landscape and battle sketches that were exhibited in Madrid and Barcelona, and resulted in him being commissioned to paint a large diorama showing one of the successes of the Spanish Army in Morocco, the capture of two Arab camps in the Battle of Tétouan.

Marià Fortuny (1838–1874), Arabs Walking in a Storm (1862-64), watercolor on paper (papel vitela grueso), 17 x 25 cm, Biblioteca Nacional de España, Madrid, Spain. Wikimedia Commons.

Fortuny’s quick watercolour sketch of Arabs Walking in a Storm (1862-64) appears to have been painted in front of the motif, during a windstorm in Morocco.

Marià Fortuny (1838–1874), Camels Reposing, Tangiers (1865), brush and watercolour over black graphite underdrawing, on off-white paper, 21 x 37.5 cm, The Metropolitan Museum of Art (Catharine Lorillard Wolfe Collection, Bequest of Catharine Lorillard Wolfe, 1887), New York, NY. Wikimedia Commons.

His Camels Reposing, Tangiers (1865) is a watercolour sketch made over a heavily-worked and now visible graphite drawing, showing a group of camels resting near the city of Tangier, not far from Tétouan, in northern Morocco.

Tomorrow we’ll rejoin Fortuny during a later visit to Morocco.