Commemorating Þórarinn B. Þorláksson, a founding father of painting in Iceland

Iceland is like no other place on earth. Sat astride the Mid-Atlantic Ridge, its landscape is dominated by active volcanoes, glaciers, waterfalls, and steppe. With its small population and their long struggle to survive against the elements, local painting was limited until the early twentieth century. Then several Icelandic painters founded what has rapidly grown into one of the most active arts for its size.

Þórarinn Benedikt Þorláksson (1867-1924) was one of the founding fathers of modern painting in Iceland, the first Icelander to exhibit in Iceland, and painted superb landscapes portraying the beauty of the land. He died at the age of only 57 a century ago, on 10 July 1924.

He initially trained and worked as a bookbinder, but in the late nineteenth century became a pupil of Þóra Thoroddsen, an Icelandic woman who had trained in Copenhagen, Denmark. Þórarinn was awarded the first public grant to support his studies, and from 1895-99 he too studied in Copenhagen. On his return in 1900, he held his first exhibition in its capital Reykjavík, the first exhibition of paintings by an Icelander to be held in Iceland.

He taught drawing, and was the principal of the Reykjavík Technical College from 1916-22. He not only inspired and taught other artists, but even supplied them with materials and books from his art shop in the city. By any standards, he was a superb landscape painter who deserves international recognition.

Þórarinn B. Þorláksson (1867-1924), King Fredrik VIII of Denmark and Hannes Hafstein Governor of Iceland ride to Þingvellir in 1908 (date not known), further details not known. Wikimedia Commons.

For much of its history, Iceland was a colony, of either Norway or Denmark. Through the nineteenth century, there was a growing independence movement, but it didn’t become a sovereign state until 1918, even then remaining in union with Denmark. This undated painting shows King Fredrik VIII of Denmark and Hannes Hafstein Governor of Iceland ride to Þingvellir in 1908, a time when the country was still a Danish colony.

Þórarinn B. Þorláksson (1867-1924), The Artist’s Home (1924), media not known, 35 x 25 cm, location not known. Wikimedia Commons.

Until relatively recently, Icelandic society was very traditional, and even homes in the city were decorated in more traditional style. Þórarinn’s glimpse into The Artist’s Home (1924) shows this well.

Þórarinn B. Þorláksson (1867-1924), Summer Evening in Reykjavík (1904), media not known, 47.5 x 77.5 cm, location not known. Wikimedia Commons.

Iceland has a strong and deep attachment to the sea, and it’s appropriate that Þórarinn’s Summer Evening in Reykjavík (1904) shows a view from its rocky coast, rather than the city’s buildings.

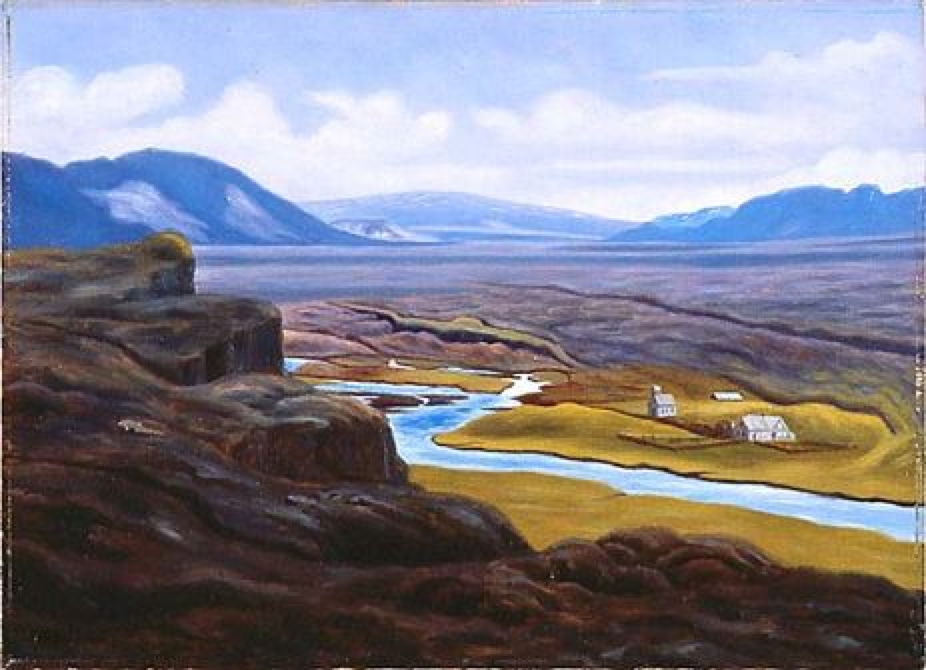

Þórarinn B. Þorláksson (1867-1924), Þingvellir (1900), media not known, 57.5 x 81.5 cm, location not known. Wikimedia Commons.

One of the central motifs in Þórarinn’s paintings is Þingvellir (1900), the site of Iceland’s original parliament in 930 CE, about thirty miles east of the capital. This is a unique site, which I found haunting for both its history – the last parliament sat here in 1798, almost 900 years after the first – and its location. It’s in a rift valley forming the boundary between the tectonic plates of North America and Eurasia, and is now a World Heritage Site.

Þórarinn B. Þorláksson (1867-1924), From Þingvellir (1914), further details not known. Wikimedia Commons.

Þórarinn painted fine views from this location, including From Þingvellir (1914), above, and From Þingvellir II (1905), below. These show Þingvallavatn, the largest natural lake in Iceland (above), and the river Öxará winding around Þingvellir (below).

Þórarinn B. Þorláksson (1867-1924), From Þingvellir II (1905), further details not known. Wikimedia Commons.

Þórarinn B. Þorláksson (1867-1924), Hekla from Laugardalur (1922), media not known, 96.5 x 128 cm, location not known. Wikimedia Commons.

Another view epitomising Iceland is that of the huge active volcano Hekla from Laugardalur (1922). Known to visitors as the Gateway to Hell, it last erupted in early 2000. Þórarinn captures it bathed in the low, warm light of sunset, seen from a park on the outskirts of Reykjavík. If this looks praeternatural, it’s because it is.

Þórarinn B. Þorláksson (1867-1924), Stórisjór og Vatnajökull (1921), further details not known. Wikimedia Commons.

Stórisjór and Vatnajökull (1921) shows this barren hilly area with its lakes, and the vast dome of the Vatnajökull glacier in the far distance. Vatnajökull is the largest in Iceland, and one of the largest in Europe, with an average ice depth of 380 metres (1,250 feet).

Þórarinn B. Þorláksson (1867-1924), Repose (1910), further details not known. Wikimedia Commons.

During the summer, the countryside of Iceland is carpeted with flowers and rich vegetation, shown well in Repose (1910).

Þórarinn B. Þorláksson (1867-1924), Waterfall (1909), media not known, 26 x 39.5 cm, location not known. Wikimedia Commons.

Þórarinn’s Waterfall (1909) is small by comparison with Iceland’s famous falls, but shows his distinctive style.

Þórarinn B. Þorláksson continued to paint the landscape of Iceland until he died at his summerhouse on 10 July 1924.

(I apologise for the limited quality of some of these images, but they are the best that are available.)