Snapshots aren’t backups

Most backup utilities now make snapshots of volumes they’re backing up, and Time Machine goes further by using snapshots in its backup process, and creating backups as snapshots. How then should we include snapshots in our backup plans? Could we rely on snapshots rather than conventional backups?

APFS snapshots

Each snapshot contains a complete set of the file system metadata for that volume at the time the snapshot was made, and all the extents required to reinstate that volume. Although tied to that volume, the snapshot is stored alongside the current volume metadata, in the same APFS container, in the same disk partition.

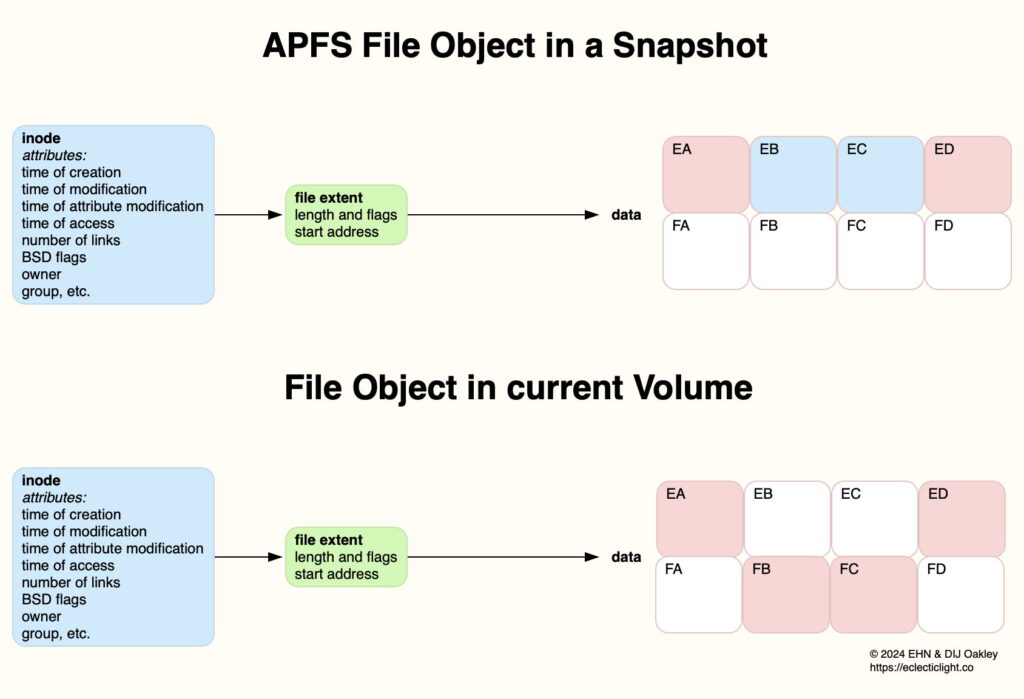

Extents list the storage blocks containing the data that composes every file that existed within that volume at the time the snapshot was made. Many of those will be the same as in the current volume, but the remainder will refer to data that has been deleted since the snapshot was made, but is being retained to enable the volume to be rolled back to its previous state. Those old extents can only be removed when that snapshot is deleted, which thus frees all those storage blocks at the same time. This is illustrated in the diagram.

This shows the same file in a snapshot and the current volume. Extents for the data of the earlier version of that file contained in the snapshot are shown at the top, and consist of blocks EA, EB, EC and ED. After that snapshot was made, the file was edited and then consists of the blocks shown at the bottom, EA, FB, FC and ED.

Thus, the extents listed for that file in the snapshot consist of two blocks, EA and ED, that are currently in use and included in its extents now, and two blocks, EB and EC, that were deleted after the snapshot was made. However, as those are referenced in the snapshot’s extents, those storage blocks are retained to enable the snapshot to restore the volume’s previous state. When that snapshot is deleted, blocks EB and EC will then be returned to the pool of free blocks for erasure and re-use.

This demonstrates how snapshots depend on their own file system metadata, and a combination of currently used storage blocks and those awaiting return for re-use.

Rolling back to a snapshot

The most popular reason for wanting to roll back to a snapshot is to recover from problems following a macOS update. As the System volume isn’t included among backup snapshots, and the process of rolling back would be so complex that it’s probably not possible, there’s no point in considering the use of snapshots for that purpose.

In other circumstances, where part or all of a user volume is to be restored from a snapshot, once that snapshot has been mounted, the procedure is the same as for restoring from a backup. What is different is that restoring a whole volume from a snapshot is a one-way trip, and there is no undo. This is because snapshots subsequent to that used to restore from will be removed, and you won’t then be able to ‘roll forward’ to a later snapshot. That contrasts with a normal backup, where items remain available from any other backup that is retained in the backup store.

Snapshot robustness

Long before the introduction of APFS, Time Machine created its own form of snapshots when a Mac was away from its normal backup store. Those enabled anyone travelling without an external drive to have limited ability to restore lost or damaged files despite their lack of conventional backups. Experience showed this to be useful in the event of human error, such as accidental deletion of files, but of limited or no use when there were file system errors.

Because snapshots share the same container as the current volume, and share many file extents with them, they are prone to common errors. In particular, common file extents make it more likely that faults occurring in extents and data storage will affect them both. This is particularly important as one of the most common file system errors that corrupts data in files occurs when extents for two separate files overlap. A snapshot is thus more vulnerable than a backup on a different disk, or even one in a different container on the same physical store.

Snapshots are whole-volume

Snapshots do have one specific advantage over backups when it comes to their coverage. As they include the whole file system metadata for the volume, no items present in that volume are excluded from its snapshots. If you want to restore an item that has been excluded from backups made of any volume, you can therefore do that from its latest snapshot, if that item was present in the volume at the time that was made.

The only disadvantage to this is that snapshots can be disproportionately large compared to volume backups. If large and ever-changing files such as Virtual Machines are excluded from backing up, but are in a volume for which snapshots are made, those snapshots may appear excessively large. The solution is to move those files to a separate volume, for which snapshots aren’t made. This behaviour can also raise privacy concerns over data that aren’t encrypted on disk, as they too will be accessible in that volume’s snapshots even when excluded from its backups.

Conclusions

Because snapshots contain metadata and data common to the current version of a volume, and share the same container, they are prone to common errors.

Restoring a snapshot can’t be undone, and removes later snapshots.

Snapshots are a useful addition to conventional backups made to separate storage, but can’t replace them.

When conventional backups aren’t available, snapshots can be invaluable.

Snapshots can be used to restore items that were excluded from backups.

Snapshots can’t be used to roll back from a bad macOS update.