Last Week on My Mac: Did Apple forget its own App Store?

I was sorely tempted to pre-order an Apple Vision Pro, but it wasn’t the cost that was the decider. When I checked, I realised that Apple has locked in its most exciting new technology to running only what’s provided through its App Store. Not that I don’t buy through Apple’s App Stores, but if there’s one thing that stultifies innovation, it’s a bureaucracy that obsesses with its rules.

It took Steve Jobs a while to accept that iPhones needed third-party apps, and Apple launched its iTunes App Store for iOS in 2008, just over a year after the first iPhone had been released. Early in 2011, the Mac followed suit, but as an addition to well-established direct distribution. At first it provided a convenient central platform for Apple’s own products.

Although promoted for its curation, security and trustworthiness, over the last 13 years each has been profoundly undermined. You don’t have to spend long looking in the App Store app to appreciate that it’s as well curated as a painting exhibition requiring all frames to be gilded and more than two inches wide, let alone the prevalence of scam apps on iOS App Stores.

Its track record of security nearly came to grief in 2015, when hundreds of apps on the China store were discovered to have been victims of a supply-chain attack by XcodeGhost. Just a couple of months later the macOS App Store suffered major problems with its security certificates, causing most of its apps to be unusable and erroneously reported as damaged.

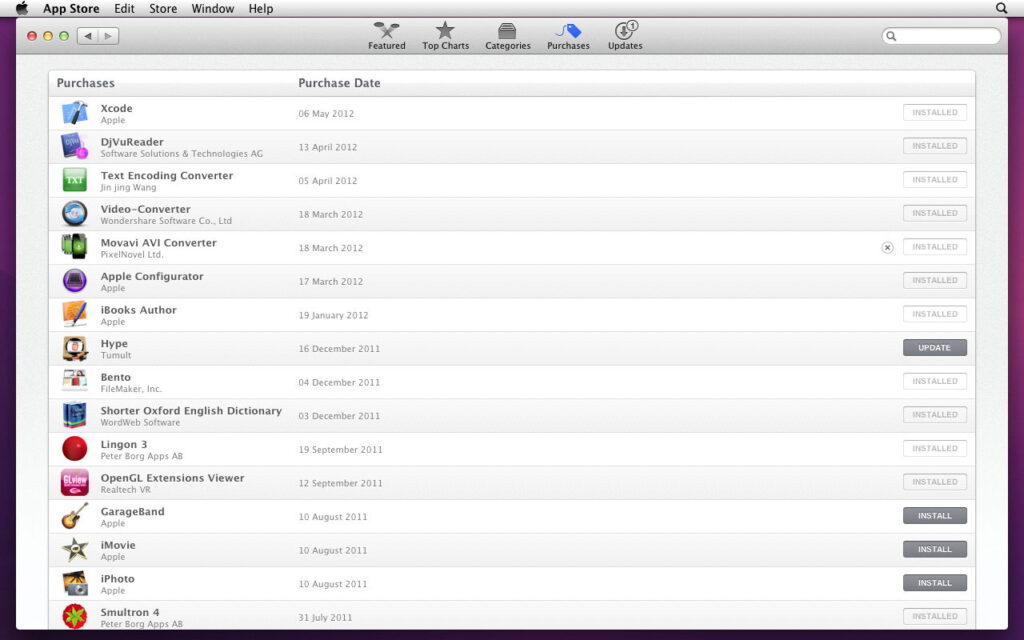

Nevertheless it has continued to attract important apps from major developers, as shown below in 2015, when it was far more navigable.

Despite being mired in controversy since they were unleashed, Apple’s App Stores have prospered, both for Apple and for the precious few developers who achieve success on them. The one growth area that they have so far missed out on has been virtual machines running on Apple silicon Macs, which have been unable to access the macOS App Store, or to run the great majority of apps purchased from it.

Shortly after Apple released lightweight virtualisation for Apple silicon Macs in 2022, those who had started to experiment with them discovered what appeared to be a major blind spot in their design: as they didn’t support signing in with an Apple ID, they could neither access iCloud services, nor run third-party apps supplied through the App Store. Obvious though this shortcoming was to users, it apparently hadn’t occurred to Apple, who hadn’t even started to build in support for Apple ID.

This was completed in time to be included among the new features announced for macOS Sequoia last month, when Apple promised that it “supports access to iCloud accounts and resources when running macOS in a virtual machine (VM) on Apple silicon”. With issues of virtualising what was needed from the host’s Secure Enclave apparently solved, some of us had come to expect that would include App Store access, which is also controlled by Apple ID. It’s now clear that Apple didn’t intend to include its App Store as a “related application”, which was implicitly excluded.

However little you might love the App Store, support in macOS VMs is essential if they are to be of any general use. VMs that can’t run all App Store apps as part of the benefits of signing in with an Apple ID are so stunted as to be of little use. Would it be that difficult to implement, now that those VMs can be signed in to all the other services that depend on an Apple ID? Did Apple really forget its own App Store when deciding what apps should be allowed to run in a VM?

If you consider this to be a showstopper for virtualising macOS on Apple silicon Macs, then please make it clear to Apple through Feedback.