A painted visit to Istanbul and Turkey 1

There can be few cities in the world as exciting as Istanbul, as it straddles the Bosporus Strait joining Europe to Asia, and connecting the Black Sea with the Mediterranean. This weekend I invite you to join me in seeing that city, and a little of the country around it, in the paintings of great artists.

Founded as the Greek city of Byzantium at around the time of Homer, it grew into the capital of Constantine the Great’s Roman Empire in 330 CE, and was soon renamed Constantinople. It then served as the capital of a succession of Byzantine and Ottoman Empires, and was finally renamed Istanbul in 1930.

Jean-Léon Gérôme (1824–1904) The Great Bath of Bursa (1885), oil on canvas, 70 x 100.5 cm, Private collection. Wikimedia Commons.

Jean-Léon Gérôme’s 1885 painting of The Great Bath of Bursa is an intricate orientalist fantasy set in this large city in north-western Turkey, which for a period during the fourteenth century was the country’s capital. This is to the south of Istanbul, close to the Sea of Marmara.

Artist not known, Charlemagne in Constantinople (c 1450), miniature on parchment in book by Sébastien Mamerot, Bibliothèque nationale de France, Paris. Wikimedia Commons.

Legends about Charlemagne and his travels are often colourful, but usually unsupported by evidence. This miniature showing Charlemagne in Constantinople from about 1450 appears entirely fictitious, and another fantasy.

Eugène Delacroix (1798–1863), The Entry of the Crusaders into Constantinople (1840), oil on canvas, 410 x 498 cm, Musée du Louvre, Paris. Wikimedia Commons.

Eugène Delacroix’s major entry for the Salon of 1841 was The Entry of the Crusaders into Constantinople (1840), destined for display in the Salle de Croisades in Versailles. This shows an episode from the fourth crusade in 1204, in which the crusaders took Constantinople. French forces were under the command of Baldwin, Count of Flanders, and had attacked from the land, while Venetians attacked the port from the sea. Its reception was as muted as its colours.

In the middle of the nineteenth century, European artists started travelling to Turkey to paint its exotic sights.

Richard Dadd (1817–1886), Caravanserai at Mylasa in Asia Minor (1845), oil on panel, 21.3 x 30.5 cm, Yale Center for British Art, Paul Mellon Collection, New Haven, CT. Courtesy of the Yale Center for British Art.

Richard Dadd’s Caravanserai at Mylasa in Asia Minor (1845) is a fairly conventional ‘orientalist’ view of a group of travellers at what had been the ancient Greek city of Mylasa, now Milas in south-western Turkey, well to the south of Istanbul and on the Mediterranean coast.

Ivan/Hovhannes Aivazovsky (1817–1900), View of Constantinople and the Bosphorus Вид Константинополя и Босфора (1856), oil on canvas, 124.5 x 195.5 cm, Private collection. Wikimedia Commons.

View of Constantinople and the Bosphorus (1856) is one of many views that Ivan Aivazovsky made of this great city, which he visited on many occasions. The artist kept his studio in Crimea, on the northern shore of the Black Sea.

During the latter half of the nineteenth century, the Italian painter Alberto Pasini lived in Constantinople for periods of up to nine months, and painted the city and its surroundings frequently.

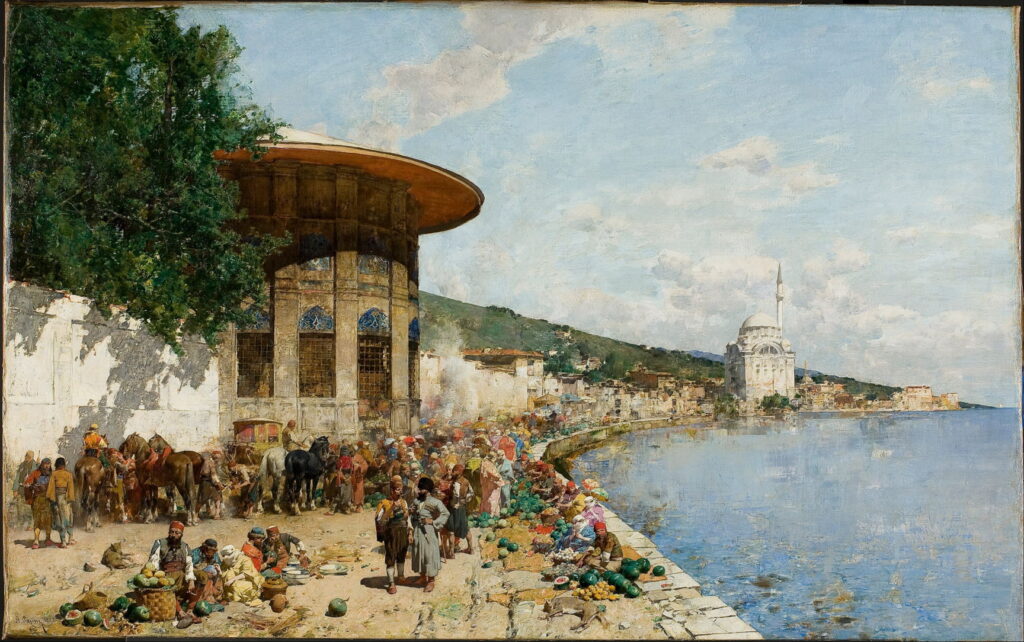

Alberto Pasini (1826–1899), Market in Istanbul (Constantinople) (1868), oil on canvas, 23.5 x 90 cm, Museo Thyssen-Bornemisza, Madrid, Spain. Wikimedia Commons.

Pasini’s great forte, if his surviving paintings are anything to go by, was the marketplace. He became very familiar with the often ad hoc markets set up wherever trading vessels came alongside. Market in Istanbul (Constantinople) from 1868 captures the cosmopolitan nature of these markets, and the whole city, mixing cultures, beliefs, eras, and technologies so gloriously.

Alberto Pasini (1826–1899), A Mosque (1872), oil on canvas, 88.9 x 66.7 cm, Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, NY. Wikimedia Commons.

Despite their apparent detail, Pasini’s paintings are relatively small, none here exceeding 90 cm (36 inches) in either dimension. The Met’s painting of A Mosque from 1872 is one of his larger works, and appears a more formal composition. A high-ranking person has just arrived in their decorated carriage to attend this mosque (see detail below), where they are greeted by a very casually turned-out guard, at the left. In the right foreground is one of Pasini’s signature melon sellers, who appear in so many of his paintings.

Alberto Pasini (1826–1899), A Mosque (detail) (1872), oil on canvas, 88.9 x 66.7 cm, Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, NY. Wikimedia Commons.

Alberto Pasini (1826–1899), At The Golden Horn (c 1876), oil on panel, 22.5 x 35.5 cm, location not known. Wikimedia Commons.

At The Golden Horn from about 1876 shows a dockside not far from the bustling city of Istanbul. The Golden Horn (in Modern Turkish, Haliç) is a horn-shaped estuary emptying into the Bosporus Strait at ‘Old Istanbul’. As a stretch of sheltered water so close to the city, it had long been a popular port for smaller traders, such as the mixed steam and sailing ship seen shrouded in coal smoke.

Alberto Pasini (1826–1899), Market Day in Constantinople (1877), media and dimensions not known, Berkshire Museum, Pittsfield, MA. Wikimedia Commons.

Market Day in Constantinople (1877) is one of Pasini’s finest paintings of the city’s waterfront, and one of several which have made their way to the US. Although its cultural fusion is less overt than his earlier painting of a market there, this is another ‘big’ view as its quay sweeps gently away into the distance. The detail below shows how meticulous Pasini is in his closer figures and produce, including the inevitable melon sellers with their great green globes glistening in the sunshine.

Alberto Pasini (1826–1899), Market Day in Constantinople (detail) (1877), media and dimensions not known, Berkshire Museum, Pittsfield, MA. Wikimedia Commons.