Could our Macs be CrowdStruck?

Thankfully, Macs weren’t affected by last week’s catastrophic CrowdStrike bug, but several of you have asked me whether macOS could be affected by something similar in the future. The short answer is that’s becoming increasingly unlikely, and for Apple silicon Macs in particular is no longer a significant risk. To understand why this is so, we need to know what happened to Windows systems with CrowdStrike protection installed, and how macOS differs.

CrowdStrike’s own account of the bug states that “an operating system crash” occurred as the result of a single logic error in one of many configuration files, known as Channel Files, that control the security protection provided by CrowdStrike’s Falcon sensor. That in turn led to the infamous Blue Screen of Death, or BSOD, the method used by Windows to inform the user that a kernel panic has occurred and the PC needs to reboot. Those configuration files are apparently automatically updated “several times a day”, without any user interaction or notification, in a long-established process used by CrowdStrike.

Researchers are currently discussing the exact point of failure and how it was able to have such serious consequences. For a single logic error to result in a kernel panic and the BSOD, it’s almost certain that the Falcon sensor runs with elevated privileges as a Kernel-Mode Driver, roughly equivalent to a kernel extension (kext) in macOS. It doesn’t seem credible that the Falcon sensor running with only user privileges would be able to bring the whole of Windows down in this way.

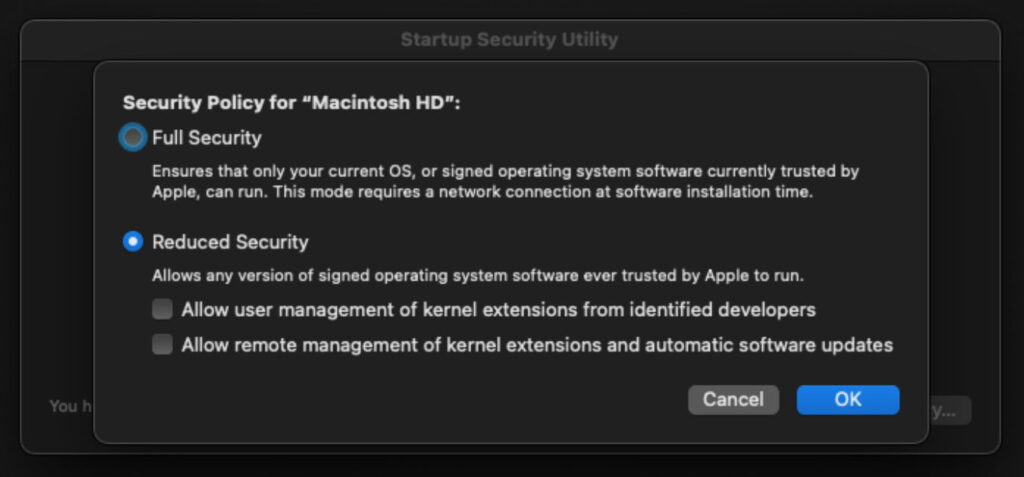

The macOS version of the Falcon sensor uses a kernel extension (kext) on Intel Macs prior to Big Sur, but because of the limitations of kexts on Apple silicon, it now uses an endpoint security System Extension instead.

Apple deprecated kexts years ago, and they can only be used on Apple silicon Macs if their startup security is dropped to Reduced Security and third-party kexts are explicitly allowed to load. For a vendor selling into enterprise and organisations, that requirement would be unacceptable to customers. As a result, almost all apps that used to use kexts have switched to modern System Extensions and their relatives. Those run with normal user privileges, so if they do go badly wrong shouldn’t be able to cause a kernel panic. They’re also designed to be installed and removed using the app that relies on them. If there’s a bug in a System Extension, you should be able to open its app and remove or update it from there.

When CrowdStrike for macOS started using a System Extension nearly four years ago, it even proclaimed that “reducing the need for privileged access is always a more secure approach and we are proud to embrace this new architecture.”

Apple’s road from kexts to System Extensions has been long, controversial, and only succeeded when Apple silicon Macs couldn’t use kexts without being run at Reduced Security. The devastation wrought by the CrowdStrike bug is vindication for all the pain that deprecation brought.

Where macOS remains at risk is with Apple’s own updates. Little more than eight years ago, on 26 February 2016, a silent automatic update to the macOS Incompatible Kernel Extension Configuration Data came close to breaking most Macs of the day. That list blocks old and incompatible kexts from being run, and version 3.28.1 inadvertently included one of Apple’s own kexts, that responsible for operating the Ethernet port on many Macs, including the latest models of iMacs and MacBook Pros at the time.

That didn’t cause a kernel panic, but once all those Macs had updated to the new version and restarted, their Ethernet ports vanished and couldn’t be used. That brought two serious problems: as the Ethernet port has been widely used to identify individual Macs, many apps were unable to run, and those without the fallback of WiFi networking were isolated from the Internet, so couldn’t download and install the emergency update that Apple released to fix the defective file.

Both Apple and macOS have come a long way since that happened in El Capitan. Although we all moan about bugs in macOS, quality control of macOS and security data updates has improved considerably, and updates have become much more consistent and reliable as a result of the Signed System Volume. The transition to Apple silicon is also simplifying testing and support with their more consistent hardware, compared to the gamut of different components used in Intel Macs.

As Rosyna Keller has written, this catastrophe wasn’t Microsoft’s fault but it is Microsoft’s problem. It’s a problem that Apple has addressed, and Microsoft has a lot to answer for in not making Windows more robust in the way that macOS is now. I suspect plenty of folk in Apple are feeling rather smug.

Summary

The CrowdStrike catastrophe occurred because a single logic error in a configuration file for its Falcon sensor escalated into a kernel panic.

This almost certainly occurred because the Falcon sensor runs with elevated privileges, in kernel space rather than user space.

Apple has almost eliminated third-party kernel extensions from macOS, replacing them with System Extensions running in user space. That has removed their propensity to cause kernel panics. In recent macOS, CrowdStrike’s Falcon sensor runs in user space as a System Extension.

Remaining risks of kernel panics are in macOS updates, which Apple has improved considerably to reduce risk.

Microsoft needs to remove third-party drivers from kernel space if Windows is to be more resilient to this type of failure.