A brief history of kernel panics

Classic Mac OS didn’t have an operating system kernel as such, so on paper at least it couldn’t suffer kernel panics. Instead, the system simply crashed or froze, and the only way out was to force the Mac to restart or shut down. In those days before the HFS+ file system gained journalling (only added to OS X 10.2.2 in 2002), that was usually followed by checking and repairing the startup disk, as the file system there was often damaged in the process.

If you were really unlucky, when your Mac tried to start up again it would display a flashing question mark indicating that the system was too damaged to be run. That’s when you reached for the startup disk or CD-ROM, or a special disk you had ready to recover your Mac and restore the system. Recovery disks were almost essential, as app crashes often brought the whole system down with them.

Mac OS X brought a big change to that, with its kernel architecture to ensure that crashing apps were less likely to cause the whole system to collapse, although early versions of the kernel and its extensions often proved less stable that we’d hoped. In the first couple of versions of Mac OS X, handling of panics was fairly basic, with lines of text displayed, and the Mac left unresponsive for the user to force it to restart.

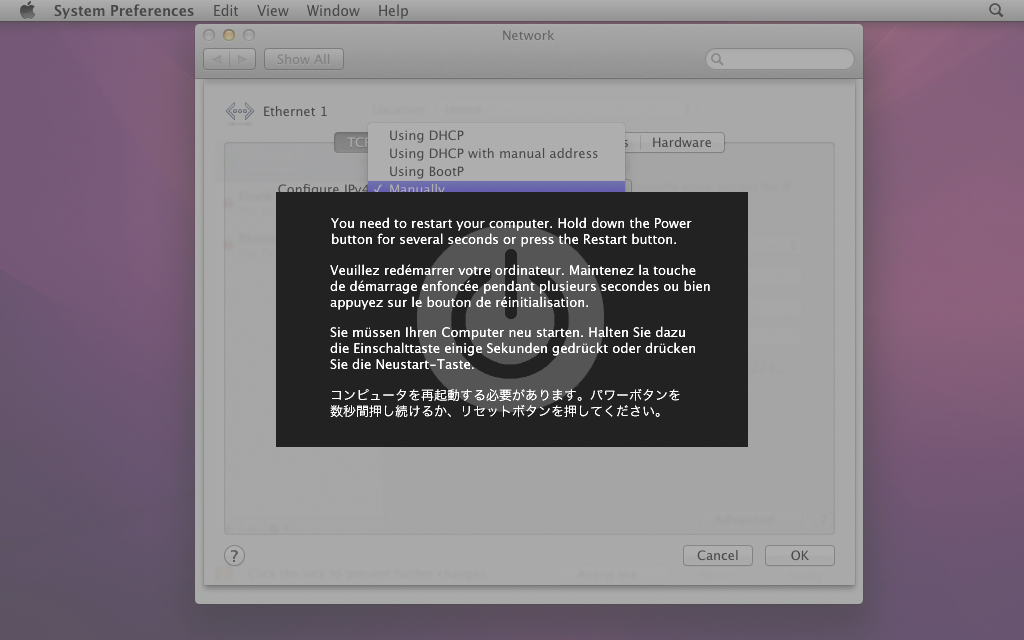

With Mac OS X 10.2 Jaguar came the well-known panic display, in which a transparent grey curtain dropped down the display to reveal a multi-language message instructing the user to restart the Mac.

A traditional kernel panic prior to OS X 10.8.

From 10.2 in 2002 through 10.7 in 2011, minor variations were made to that panic display, including additional translations of its text. Because of the practical difficulties of getting a real screenshot of this event, that shown above is a slight cheat created by overlaying the display image stored in the system on a normal screenshot, but it’s a faithful reproduction of what we saw then.

This all changed in OS X Mountain Lion, in 2012, when the panic display disappeared and the user was informed of the panic only after their Mac had restarted automatically. Apple took to referring to them not as kernel panics, but in the euphemism unexpected restarts, and then removed the multi-language message altogether.

Instead, what was intended to happen was, shortly after the user had logged back into the automatically restarted Mac, a panic alert would appear, containing the panic log. Users were encouraged to send that to Apple, and most assumed that an engineer there would review it, and perhaps even respond to it if appropriate. In reality, panic logs were automatically and anonymously processed to provide Apple with overall statistics, and it seems extremely unlikely that any human read any of them individually unless they accompanied a bug report.

Kernel panics tended to break out in small epidemics confined to specific models. My own period of purgatory lasted six months, between the release of OS X 10.11.4 on 21 March 2016 and the upgrade to Sierra on 20 September that autumn/fall. Throughout that period, many newer MacBook Pros and iMacs suffered frequent kernel panics, in my iMac’s case every 2-5 days. Those may well have resulted from bugs in their graphics drivers, but were never fixed in El Capitan, as far as I’m aware.

Despite their frequency in the past, Apple has been remarkably reluctant to admit to them in its documentation. That for users avoids all mention of the term, merely referring to them as unexpected restarts “because of a problem”. Even that for developers buries them away in an ancient Tech Note from 14 August 2008, and still contains details for PowerPC models.

Maybe we’ve just been imagining them all those years.