A brief history of Directory Services

Operating systems have to store a lot of information about users, services, machines, mounts, and all manner of other things. In traditional Unix, this had been largely accomplished using system configuration files. NeXTSTEP version 0.9 changed this in 1988 when it introduced a centralised NetInfo service. A controversial move, its acceptance was initially hampered by its inclusion of DNS name server lookups; when those failed to complete, the whole NetInfo service ground to a halt, and could lock the user out.

Nevertheless, NetInfo was built into the first versions of Mac OS X, until it was progressively replaced with Apple’s standard-based alternative named Open Directory, which first appeared in Mac OS X Server 10.2 Jaguar in 2002, and subsumed NetInfo completely in Mac OS X client and Server 10.5 Leopard.

NetInfo Manager, like its successor Directory Utility, was also used to enable the root user and set its password, important features at that time. Above is NetInfo Manager in 2001, and below shows it in the following year.

Open Directory is Apple’s implementation of the Lightweight Directory Access Protocol, LDAP, released as LDAPv3 in 1997, and Mac OS X has supported both LDAPv2 and v3. On standalone Macs, a local Open Directory database contains detailed information about each user, groups, all the other information that had previously been in NetInfo such as services, and links with the password service and Kerberos. The latter is a ticket-based authentication protocol widely used on Windows, Unix and similar systems, supporting signing-on with a single password for multiple services.

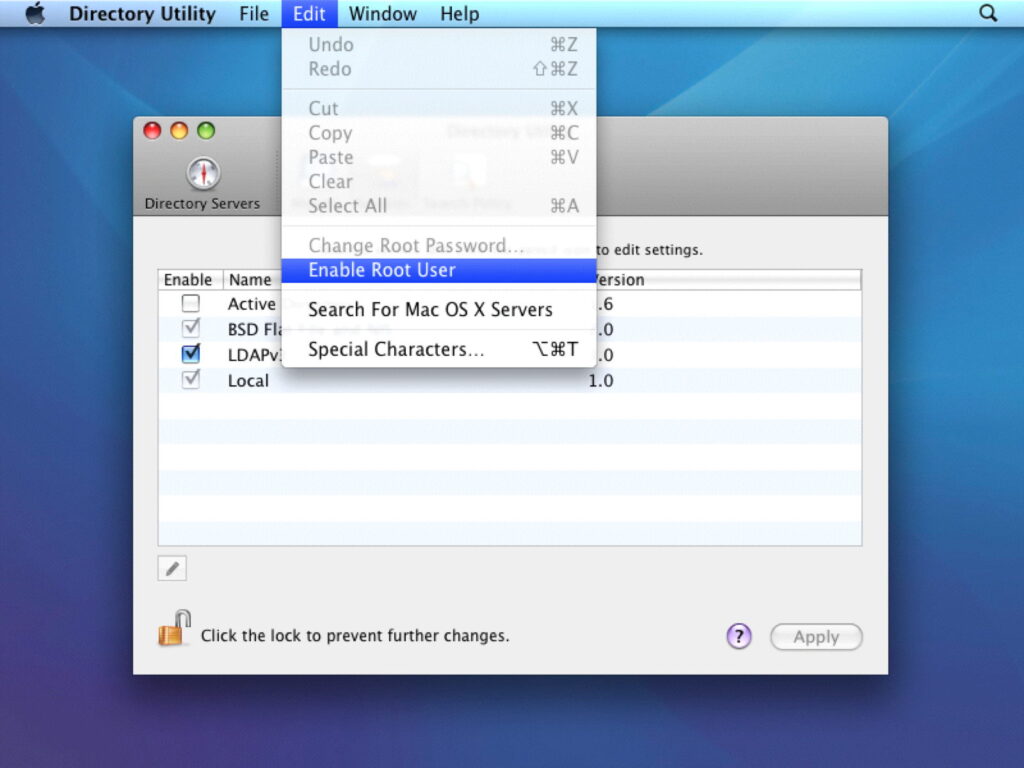

NetInfo Manager’s replacement Directory Utility is seen here in 2007, when it was still relatively new.

An example of the use of Open Directory is with file permissions. When any given user wants access to read or write a file, the system has to check, using their ID number such as 501, whether they’re the owner; failing that, it falls back to whether user 501 is a member of the group that has read-write access. Open Directory can answer the question as to whether user 501 is a member of the admin group, for example, thus allowing the system to determine what level of access user 501 has to every file and directory.

Centralised password services are another essential feature of an operating system. They allow the user to log on once and thus to gain access to all the services to which they’re privileged, instead of having to sign on to each service individually.

Open Directory’s services become even more important across a network, where users may need to log into different systems which could be in different locations. In the days of Mac OS X Server, Open Directory services were one of its key features. Clients looked up information on the server’s database, and authentication was performed against its Kerberos Key Distribution Centre, enabling a user to log onto any of the managed systems on that network. To ensure maximum availability and support up to 200,000 user records, Open Directory databases can be replicated across multiple servers.

Open Directory supports multiple platforms, including Windows and Linux as well as macOS clients. Similarly, it integrates with mixed server architectures, including Active Directory in Windows Server, and other LDAP services on Unix and Linux servers. In 2005, Apple provided a Technology Brief giving a detailed overview of Open Directory and how it worked in Mac OS X Server.

Directory Utility above is from 2011, and has evolved into the current version below.

With the effective demise of macOS Server from 2015 onwards, Open Directory is now almost exclusively seen in its cut-down role in individual macOS systems. But Open Directory and Directory Services play a prominent part in many systems within macOS, and their entries are frequent in the log. Open Directory’s section in Apple’s developer documentation is now but an empty shell, lacking descriptions and explanations.

Even for advanced macOS users, exposure to Open Directory is usually minimal, and confined to very infrequent use of Directory Utility, tucked well out of sight in the /System/Library/CoreServices/Applications folder.

Open Directory has become something of a Cinderella, still handling many fundamental tasks in macOS, even with the arrival of the Secure Enclave in T2 and Apple silicon chips. And it doesn’t have anything to do with DNS lookups.