Reading visual art: 150 Camels in narrative

Camels are very large ungulates adapted to life in the desert, famous for their ability to survive for long periods without eating or drinking, their unpleasant smell, and a notoriously bad temper. I like Wikipedia’s sense of humour when it refers to their domestication, as few companion species could be less domesticated, but that’s supposed to have happened at least three thousand years ago.

Since then camels have been a mainstay of many major trade routes, with the single-hump dromedary best-known in Europe from its distribution across northern Africa and well into the Middle East. The Bactrian camel with its two humps has a more exotic range across central Asia, as far west as Georgia. There’s even an annual beauty pageant of camels in the King Abdulaziz Camel Festival held in Saudi Arabia.

Camels have been known to European artists since ancient times, and feature in several well-established narratives.

Piero di Cosimo (1462–1522), Vulcan and Aeolus (c 1490), tempera and oil on canvas, 155.5 × 166.5 cm, National Gallery of Canada Musée des beaux-arts du Canada, Ottawa, Canada. Wikimedia Commons.

Piero di Cosimo’s account of Vulcan and Aeolus from about 1490 is one of the earliest in modern Western painting. From the left the figures are a river god, Vulcan forging a horseshoe, a figure (possibly Aeolus, keeper of the winds) riding a horse, a man curled asleep in a foetal position, a couple and their infant son, and four carpenters erecting the frame of a building. Among the animals are a giraffe and a black camel. It’s thought this shows early humans developing crafts at the start of civilisation.

Hieronymus Bosch (c 1450–1516), The Garden of Earthly Delights (centre panel) (c 1495-1505), oil on oak panel, central panel 190 × 175 cm, each wing 187.5 × 76.5 cm, Museo Nacional del Prado, Madrid. Wikimedia Commons.

They also feature in the centre panel of Hieronymus Bosch’s Garden of Earthly Delights, painted in about 1500. This shows a rolling deer park with lakes, overrun by a dense mass of naked men and women, animals and bizarre objects.

Hieronymus Bosch (c 1450–1516), The Garden of Earthly Delights (centre panel, detail) (c 1495-1505), oil on oak panel, central panel 190 × 175 cm, each wing 187.5 × 76.5 cm, Museo Nacional del Prado, Madrid. Wikimedia Commons.

The middle distance is dominated by a central circular pond, in which there are groups of people. Around them is a procession of people riding horses, camels, and other mammals, in an anticlockwise direction around the central pond. To the left and right are more groups of people interacting, apparently in playful ways, with bizarre objects, such as the tail of a massive lobster.

Camels have occasionally featured in the cavalcade of animals being charmed by Orpheus.

Aelbert Cuyp (1620–1691), Orpheus with Animals in a Landscape (Orpheus Charming the Animals) (c 1640), oil on canvas, 113 x 167 cm, Museum of Fine Arts Boston, Boston, MA. Wikimedia Commons.

Aelbert Cuyp’s Orpheus with Animals in a Landscape from about 1640 is one of at least two different paintings he made of the story. Here he has included a wide range of both domestic and exotic animals and birds, including a dromedary, a distant elephant, an ostrich, herons and wildfowl, although Orpheus is seen playing a violin rather than a lyre.

Paulus Potter (1625–1654), Orpheus and Animals (1650), oil on canvas, 67 x 89 cm, Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam. Wikimedia Commons.

Among the many superb animal paintings of Paulus Potter, Orpheus and Animals from 1650 is one of his most unusual, showing a wide range of different animal species, some of which weren’t well-known at that time, and one of which (the unicorn) didn’t even exist. Those seen include a Bactrian camel (two humps), donkey, cattle, ox, wild pig, sheep, dog, goat, rabbit, lions, dromedary (one hump), horse, elephant, snake, deer, unicorn, lizard, wolf, and monkey.

Camels also appear in paintings of Old Testament stories from the book of Genesis.

Artist not known, Rebecca and Eliezer, page in The Vienna Genesis (c 525 CE), tempera, gold, and silver paint on purple-dyed vellum, Österreichische Nationalbibliothek, Vienna. Wikimedia Commons.

This page from the Vienna Genesis from about 525 CE tells the story of Rebecca and Eliezer, from Genesis chapter 24. In his quest for a wife for his son Isaac, Abraham sent his servant Eliezer back to their homeland of Mesopotamia to look for one. Eliezer reached the city of Nahor, where he stopped to water his camels and rest from his long journey. He pulled up at a well outside the city, where a young woman, Rebecca, had just drawn water. She offered him her water, and he recognised her as the chosen bride for Isaac, so presented her with the betrothal gifts he had brought with him.

This exquisitely painted miniature uses multiplex narrative. In the background is a symbolic representation of Nahor. Rebecca is shown at the left, having walked out of the city with her pitcher on her shoulder, along a colonnade. In front of her is a pagan water nymph, presumably the spirit of that well. Rebecca is shown a second time, and at similar size, giving Eliezer her pitcher to slake his thirst. His train of relatively tiny camels is also taking water.

Benjamin West (1738–1820), Isaac’s Servant Tying the Bracelet on Rebecca’s Arm (1775), oil on canvas, 123.8 x 160.5 cm, Yale Center for British Art, New Haven, CT. Wikimedia Commons.

Benjamin West painted Isaac’s Servant Tying the Bracelet on Rebecca’s Arm in 1775. This shows Eliezer giving her two golden bracelets and a nose ring, tokens that she showed her family, and marked her as Isaac’s intended wife. The camel at the left doesn’t seem as impressed, though.

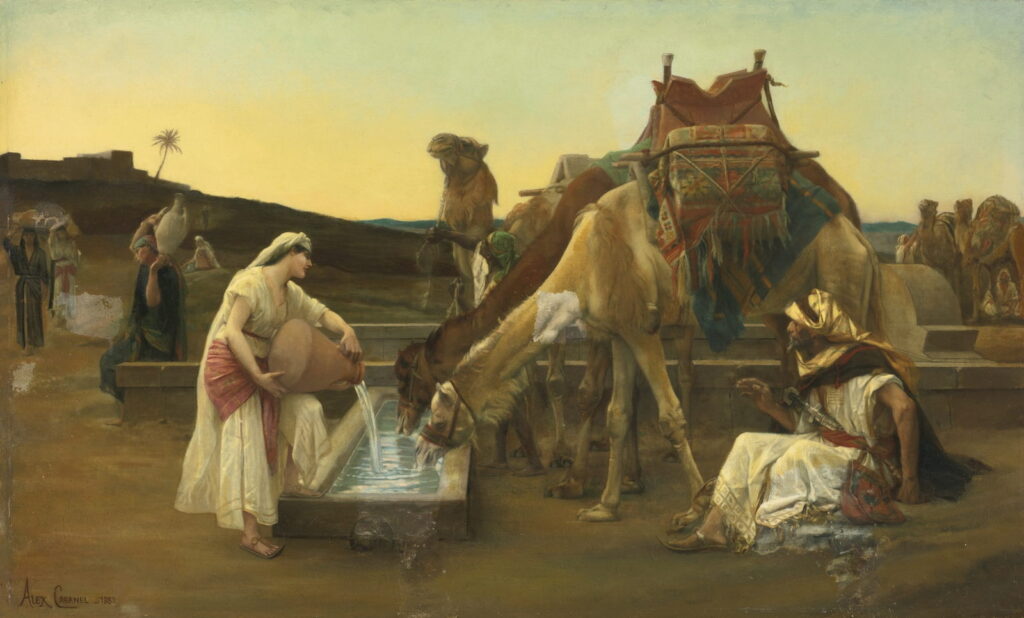

Alexandre Cabanel (1823–1889), Rebecca and Eliezer (1883), oil on canvas, 57.1 x 95.8 cm, location not known. Wikimedia Commons.

Alexandre Cabanel painted an earlier moment in his Rebecca and Eliezer from 1883, showing the camels drinking the water provided by Rebecca.

Camels have also appeared as atmospheric extras in other Biblical narratives.

Eugène Delacroix (1798–1863), Jacob Wrestling with the Angel (1854-61), oil and wax on plaster, 751 x 485 cm, Église Saint-Sulpice, Paris. Image by Wolfgang Moroder, via Wikimedia Commons.

Eugène Delacroix’s magnificent painting of Jacob Wrestling with the Angel in the church of Saint-Sulpice in Paris is drawn from the Book of Genesis, where Jacob is trying to assuage Esau’s anger by taking him flocks and gifts. He meets a stranger, an angel, who gets into a bitter quarrel with him, which is only ended when the stranger touches Jacob on the tendon of his thigh and renders him helpless. That’s the moment depicted here, as the angel’s right hand reaches under Jacob’s left thigh. To the right are flocks of sheep with Jacob’s shepherds driving them on a mixture of horses and camels.

They also appear in some accounts of the Nativity of Christ, either accompanying the Magi when they pay their respects to the infant and Holy Family, or later during the flight to Egypt.

Giotto di Bondone (1266–1337), The Adoration of the Magi (c 1305), fresco, approx 200 x 185 cm, Scrovegni Chapel, Padua. Wikimedia Commons.

Giotto’s frescoes in the Scrovegni Chapel at Padua, Italy, contain an elaborate depiction of The Adoration of the Magi from about 1305. The infant Christ rests on the Virgin Mary’s knee; she was originally clad in her signature ultramarine blue, but that has worn away with the years. Mary is accompanied by Joseph and an angel, and the Holy Family is within a wooden shed. The three ‘wise men’ pay their respects and present their gifts, here accompanied by camels and at least two attendants. The comet that attracted their attention is shown as a fireball crossing the sky.

Tomorrow’s sequel moves to show camels in more recent times.