Last Week on My Mac: Layered security and herd immunity

Reviewing security products intended to detect and remove malicious software is far harder than it used to be. There was a time when all you had to do was set your virtual machine to Reduced Security, disable SIP, and maybe Gatekeeper too, then strip any quarantine extended attributes from samples of recent malware. With nothing to trigger checks by macOS security, the malware was fully exposed to the security software under test, and you could assess how successful the product was at detection.

Yet in Sonoma it seems that you also need to disable AMFI (Apple Mobile File Integrity), or macOS will intervene to detect the malware before the product under test, which then won’t get a look-in.

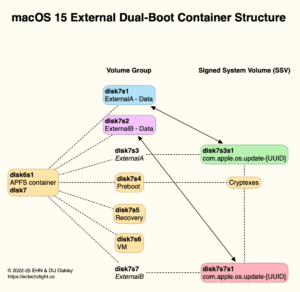

Back in Sonoma 14.4.1 I summarised those layers of checks in this diagram.

Although it’s encouraging that malware detection is now so pervasive, this makes it almost impossible to assess the other side of an anti-malware product, how well it can remove the malicious software it discovers. The same applies to Apple’s own XProtect Remediator. Stunting and tricking macOS to the point where malware can deploy fully isn’t anywhere near as easy as it was.

You know you have failed again when macOS pops up an alert like this, telling you that it has intercepted your attempt to bypass its protection.

From a user’s point of view, this can only be good. macOS security protection is designed and applied in multiple layers so that, even if something manages to trick its way past one check, the next layer is there to stop it in its tracks.

The strangest thing about XProtect Remediator isn’t the fact that, left to its own devices, it doesn’t inform the user when it detects malware, but that it will happily remove the malware it detects and let you carry on using your Mac as if nothing had happened. If you’re as old school as me, you might wonder why you shouldn’t have to wipe your Mac completely, restore it in DFU mode if an Apple silicon model, and rebuild it from scratch. Surely the slightest suspicion of anything malicious demands such a scorched earth approach?

That too depends on what security protection your Mac has active. If that includes SIP and the SSV, then there’s no known malware that can alter anything on the SSV, and what it can do on your Data and other volumes is also limited. The days of viruses wreaking havoc throughout your entire Mac thankfully seem long since past. Viruses, of course, were designed to replicate themselves throughout a Mac’s storage, but today’s trojans and stealers are after two things, and those are your secrets and money.

But that depends on the behaviour of potential victims of malware. Like any business, those who try to profit from theft of our secrets and other malicious behaviour have to consider the size of their market of victims. For many years, this was one of the Mac’s defences against malware: why would anyone want to develop for such a small proportion of potential victims, when PCs readily provided far more? More recently, some have unfortunately recognised our potential, and now we’re suffering the consequences.

This is where standard macOS security protection comes into play. At present, the great majority of Macs running Big Sur or later have SIP enabled and their SSV fully protected. The victim market for malware requiring write access to the System volume is tiny. But what if it became more usual for Macs to be unprotected, and all that malware had to do was gain root privileges to be able to write to the System volume?

This is a phenomenon akin to vaccination and resulting herd immunity in pandemics like Covid. States and nations with low protection by vaccination and little herd immunity suffered the highest rates of infection and consequent death rates. But so few realised that exercising their personal choice to remain unvaccinated had that effect, despite the fact that humans throughout the world had eliminated the deadly disease of smallpox by building herd immunity in the late twentieth century.

Security protection in macOS works in layers. Each layer you disable opens wider the window of opportunity for attackers. The more Macs that have any given layer of protection disabled, the lower the herd immunity to attack, and the more likely that malware will try to take advantage of that.