Emily Carr’s paintings: First totems 1892-1911

Few of us ever get to visit the Pacific North-West, but one painter, more than anyone else, has defined its ‘look’. She’s also one of a very few prolific women artists for whom there are sufficient good images to justify a short series of articles: she is Emily Carr (1871–1945), one of the major painters of North America.

She was born in Victoria, British Columbia, in 1871, to parents who had emigrated from England. Their large family was quite affluent thanks to her father’s business dealings, but her mother died of tuberculosis when Emily was only fourteen, and her father died two years later. Thanks to her guardian, Carr started studies at the California School of Design in San Francisco in 1890, but in 1893, when family finances became tight, she had to return home.

Emily Carr (1871–1945), Melons (1892), oil on canvas, dimensions not known, Provincial Archives of British Columbia, Victoria, BC. The Athenaeum.

Her still life of Melons dates from those years as a student in California, in 1892.

Back in Victoria, she started teaching art in her studio, enabling her to save up enough money to study abroad again.

Emily Carr (1871–1945), Cedar Cannibal House, Ucluelet, BC (1898), watercolour, 17.9 x 26.5 cm, Provincial Archives of British Columbia, Victoria, BC. The Athenaeum.

In 1898, she travelled to Ucluelet, on the west coast of Vancouver Island, where she stayed among the Nuu-chah-nulth (‘Nootka’) people, her first exposure to First Nations culture. Cedar Cannibal House, Ucluelet, BC (1898) is a watercolour made during that visit. This group of tribes had early contact with European settlers; they had suffered badly from epidemics of infectious disease, and at the time that Carr visited, their population had probably fallen to around 3,500.

The following year, Carr travelled to London, where she studied at the Westminster School of Art. She found the teaching there was too conservative, and didn’t cope well with conditions in the sprawling city, so left there in 1901 to visit Paris, and later the Saint Ives art colony in Cornwall. She stayed there through the winter, being taught in the Porthmeor Studios by Julius Olsson (1864-1942) and his assistant. She later studied further in Hertfordshire under John Whiteley.

Carr then became unwell, and in 1903 entered the East Anglian Sanatorium with a diagnosis of hysteria. She was unable to paint there, and managed to return to Canada in 1904. She resumed teaching, this time in Vancouver. However, she didn’t get on well with society women who attended her classes, and they complained of her behaviour of smoking and swearing at them in class.

Emily Carr (1871–1945), Breton Church (1906), oil on canvas, dimensions not known, Private collection. Wikimedia Commons.

Carr’s Breton Church (1906) is a puzzle, as she was back in Canada at that time, and didn’t paint in Brittany until after 1910. This image also suggests that it’s high in chroma, which would have been more likely during or after her time studying with Harry Gibb there, when her style became overtly Fauvist.

In 1907, Emily and her sister Alice travelled to see the sights of Alaska, where she was enthralled by the totem poles of Sitka. It was here that Emily Carr first resolved to document the totems and First Nations villages of British Columbia, which may have been influenced by Theodore J Richardson (1855-1914), an American artist who spent years documenting in his paintings the peoples of Sitka and Alaska more generally.

Emily Carr (1871–1945), Skagway (1907), watercolour, 26.4 x 35.7 cm, Provincial Archives of British Columbia, Victoria, BC. The Athenaeum.

One of the places that she visited was Skagway (1907), painted here in watercolour. Then a bustling small city, it was the port of entry to the south-east ‘pan-handle’ of Alaska. It had expanded greatly with the gold rush of 1897 onwards, but by the time that the Carr sisters visited that was long since over, and the economy was in sustained decline.

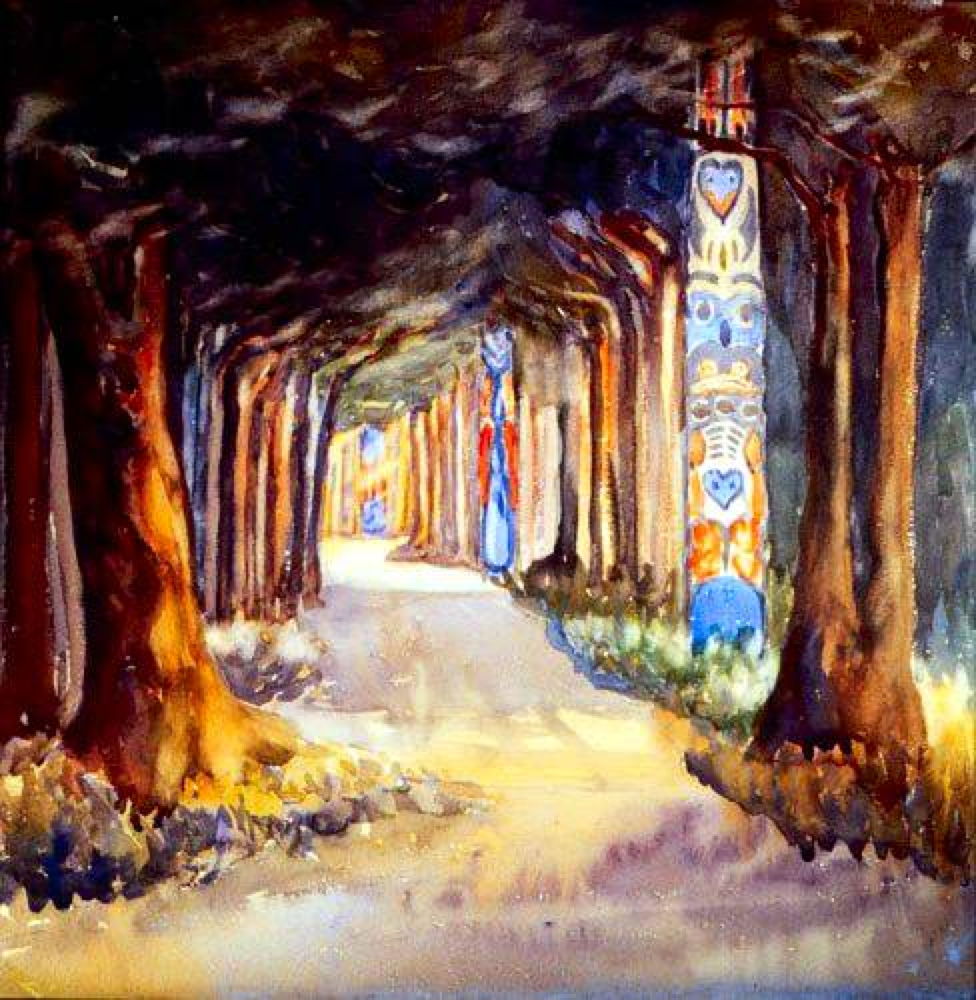

Emily Carr (1871–1945), Totem Walk at Sitka (1907), watercolour on paper, dimensions not known, Art Gallery of Greater Victoria, Victoria, BC. The Athenaeum.

The sisters also visited Baranof Island, where they saw the famous Totem Walk at Sitka (1907), shown in this watercolour. These totems were made by the Tlingit and Haida peoples, but had been removed from their original locations for display at the St Louis World’s Fair in 1904. Following that, they were moved again into this newly constructed National Park.

Emily Carr (1871–1945), Arbutus Tree (c 1909), watercolour on paper, 54.7 x 38 cm, Art Gallery of Greater Victoria, Victoria, BC. The Athenaeum.

Carr’s fascination with trees in the landscape developed early during her career. Her Arbutus Tree (c 1909) is a sophisticated watercolour portrait of one such tree, probably painted near Vancouver.

Emily Carr (1871–1945), Beacon Hill Park (1909), watercolour on paper, 35.2 x 51.9 cm, Art Gallery of Greater Victoria, Victoria, BC. The Athenaeum.

Beacon Hill Park (1909) is a watercolour in Impressionist style, showing a small corner of this 200 acre park in Victoria, on Vancouver Island. This overlooks Juan de Fuca Strait, and is shown here with the flowers of late spring or early summer, with arbutus trees in the distance. The Carr family home bordered on this park.

Emily Carr (1871–1945), Wood Interior (1909), watercolour on paper, 72.5 x 54.3 cm, Vancouver Art Gallery, Vancouver, BC. The Athenaeum.

Carr also started painting distinctive works showing the dense trunks of a Wood Interior (1909), here lit powerfully by rays of low sunshine. This was to remain a recurrent motif throughout her career.

Emily Carr (1871–1945), Alert Bay (1910), watercolour and graphite on paper, 76.7 x 55.3 cm, Vancouver Art Gallery, Vancouver, BC. The Athenaeum.

Alert Bay (1910) is another watercolour, showing a small village on Cormorant Island, at the opposite (north) end of Vancouver Island from Victoria. Home to the ‘Na̱mg̱is nation of the Kwakwaka’wakw, this illustrates her rapidly developing interest in documenting the totems of the north-west coastal area.

In 1910, Carr returned to Paris with her sister Alice, for a further year of study. Again she found living in a big European city was stifling, and spent time in a spa in Sweden. She studied with Harry Phelan Gibb (1870-1948) at Crécy-en-Brie just outside Paris, and in Brittany. This was her first exposure to Fauvism, and proved a major influence on her style.

Emily Carr (1871–1945), Autumn in France (1911), oil on board, dimensions not known, National Gallery of Canada / Musée des beaux-arts du Canada, Ottawa, ON. Wikimedia Commons.

I suspect that Carr’s already high chroma has been further exaggerated in this image of her famous painting of Autumn in France (1911), representing her Fauvism at its height. She uses bold and confident brushstrokes rich with raw colour to show the countryside of Brittany in brilliant summer sunlight.

Two of Carr’s paintings were accepted for the autumn Salon in Paris in 1911. She returned to Vancouver in 1912, and promptly exhibited her Fauvist work in her studio there. She then set out on her project to document the First Nations peoples of the north-west coast, as I’ll relate in the next article in this series.

References

Wikipedia.

Lisa Baldissera (2015) Emily Carr, Life & Work, Art Canada Institute. ISBN 978 1 4871 0044 5. Available in PDF from Art Canada Institute.

Ian M Thom (2013) Emily Carr Collected, Douglas & McIntyre. ISBN 978 1 77100 080 2.