A brief history of defragging

When the first Macs with internal hard disks started shipping in 1987, they were revolutionary. Although they still used 800 KB floppy disks, here at last was up to 80 MB of reliable high-speed storage. It’s worth reminding yourself of just how tiny those capacities are, and the fact that the largest of those hard disks contained one thousand times as much as each floppy disk. By the 1990s, with models like the Mac IIfx, internal hard disks had doubled in capacity, and reached as much as 12 GB at the end of the century.

Over that period we discovered that hard disks also needed routine maintenance if they were to perform optimally, and all the best users started to defrag their hard disks.

Consider a large library containing tens or even hundreds of thousands of books. Major reference works are often published in a series of volumes. When you need to consult several consecutive volumes of such a work, how they’re stored is critical to the task. If someone has tucked each volume away in a different location within the stack, assembling those you need is going to take a long while. If all its volumes are kept in sequence on a single shelf, that’s far quicker. That’s why fragmentation of data has been so important in computer storage.

The story of defragging on the Mac is perhaps best illustrated in the rise and fall of Coriolis Systems and iDefrag. Coriolis was started in 2004, initially to develop iPartition, a tool for non-destructive re-partitioning of HFS+ disks, but its founder Alastair Houghton was soon offering iDefrag, which became a popular defragging tool. This proved profitable until SSDs became more widespread and Apple released APFS in High Sierra, forcing Coriolis to shut down in 2019, when defragging Macs effectively ceased.

All storage media, including memory, SSDs and rotating hard disks, can develop fragmentation, but most serious attention has been paid to the problem on hard disks. This is because of their electro-mechanical mechanism for seeking to locations on the spinning platter they use for storage. To read a fragmented file sequentially, the read-write head has to keep physically moving to new positions, which takes time and contributes to ageing of the mechanism and eventual failure. Although solid-state media can have slight overhead accessing disparate storage blocks sequentially, this isn’t thought significant and attempts to address that invariably have greater disadvantages.

Fragmentation on hard disks comes in three quite distinct forms: file data across most of the storage, file system metadata, and free space. Different strategies and products have been used to tackle each of those, with varying degrees of success. While few doubt the performance benefits achieved immediately after defragging each of those, little attention has been paid to demonstrating more lasting benefits, which remain more dubious.

Manually defragging HFS+ hard disks was always a questionable activity, as Apple added background defragmentation to Mac OS X 10.2, released two years before Coriolis was even founded. By El Capitan and Sierra that built-in defragging was highly effective, and the need for manual defragging had almost certainly become a popular myth. Neither did many consider the adverse effects on hard disk longevity of those intense periods of disk activity.

The second version of TechTool Pro in 1999 offered a simplified volume map for what it termed optimisation, offering the options to defragment only files, or the whole disk contents including free space.

By the following year, TechTool Pro was paying greater attention to defragging file system metadata, here shown in white. This view was animated during the process of defragmentation, showing its progress in gathering together all the files and free space into contiguous areas. TechTool Pro is still developed and sold by MicroMat, and now in version 20.

A similar approach was adopted by its competitor Speed Disk, here with even more categories of contents.

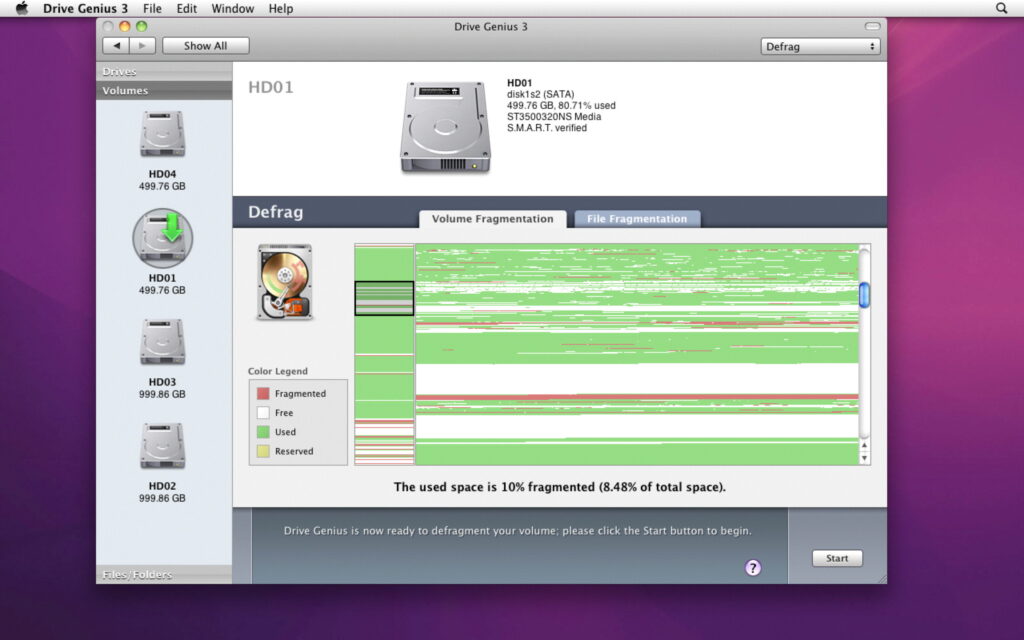

By 2010, my preferred defragger was Drive Genius 3, shown here working on a 500 GB SATA hard disk, one of four in my desktop Mac; version 6 is still sold by Prosoft. One popular technique for defragmentation with systems like that was to keep one of its four internal disks empty, then periodically clone one of the other disks to that, and clone it back again.

Alsoft’s DiskWarrior is another popular maintenance tool, shown here in 2000. This doesn’t perform conventional defragmentation, but restructures the trees used for file system metadata, and remains an essential tool for anyone maintaining HFS+ disks.

Since switching to APFS on SSDs several years ago, I have missed defragging like a hole in the head.