Last Week on My Mac: M4 incoming

Almost exactly a year after it released its first Macs featuring chips in the M3 family, Apple has replaced those with the first M4 models. Benchmarkers and core-counters are now busy trying to understand how these will change our Macs over the coming year or so. Before I reveal which model I have ordered, I’ll try to explain how these change the Mac landscape, concentrating primarily on CPU performance.

CPU cores

CPUs in the first two families, M1 and M2, came in two main designs, a Base variant with 4 Performance and 4 Efficiency cores, and a Pro/Max with 8 P and 2 or 4 E cores, that was doubled-up to make the Ultra something of a beast with its 16 P and 4 or 8 E cores. Last year Apple introduced three designs: the M3 Base has the same 4 P and 4 E CPU core configuration as in the M1 and M2 before it, but its Pro and Max variants are more distinct, with 6 P and 6 E in the Pro, and 10-12 P and 4 E cores in the Max. The M4 family changes this again, improving the Base and bringing the Pro and Max variants closer again.

As these are complicated by sub-variants and binned versions, I have brought the details together in a table.

I have set the core frequencies of the M4 in italics, as I have yet to confirm them, and there’s some confusion whether the maximum frequency of the P core is 4.3 or 4.4 GHz.

Each family of CPU cores has successively improved in-core performance, but the greatest changes are the result of increasing maximum core frequencies and core numbers. One crude but practical way to compare them is to total the maximum core frequencies in GHz for all the cores. Strictly speaking, this should take into account differences in processing units between P and E cores, but that also appears to have changed with each family, and is hard to compare. In the table, columns giving Σfn are therefore simply calculated as

(max P core frequency x P core count) + (max E core frequency x E core count)

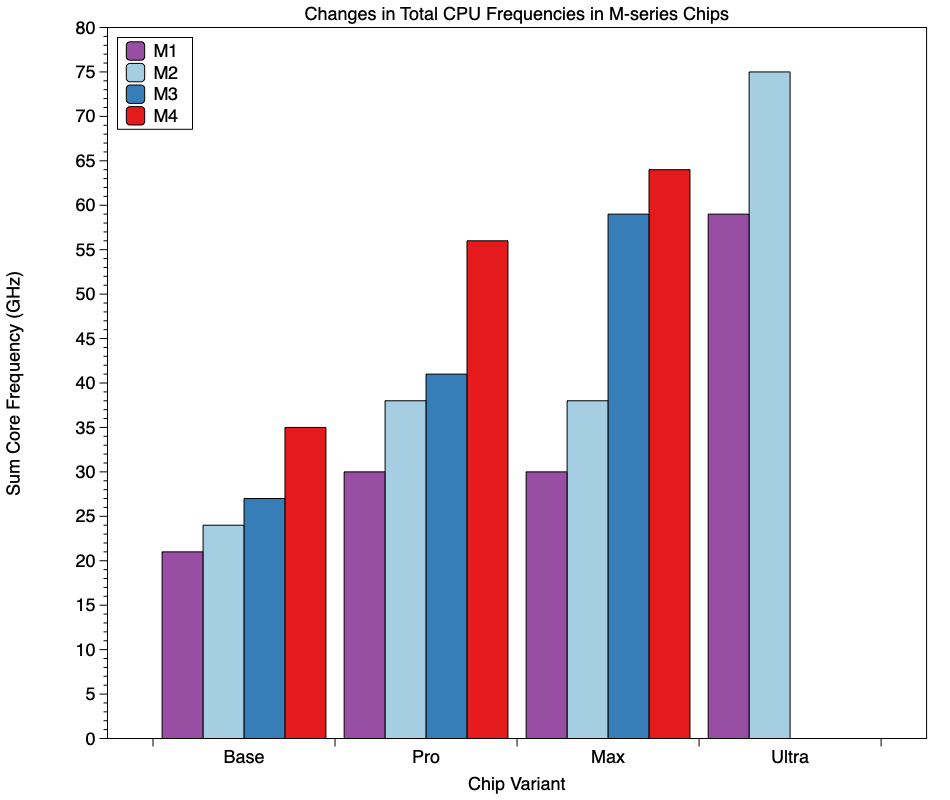

Plotting those sum core frequencies by variant for each of the four families provides some interesting insights.

Here, each bar represents the sum core frequency of each full-spec variant. Those are grouped by the variant type (Base, Pro, Max, Ultra), and within those in family order (M1 purple, M2 pale blue, M3 dark blue, M4 red). Many trends are obvious, from the relatively low performance expected of the M1 family, except the Ultra, and the changes between families, for example the marked differences in the M4 Pro, and the M3 Max, against their immediate predecessors.

Sum core frequencies fall into three classes: 20-30, 35-45, and greater than 55 GHz. Three of the four chips in the M1 family are in the lowest of those, with only the M1 Ultra reaching the highest. The M4 is the first Base variant to reach the middle class, thanks in part to its additional two E cores. Two of the M4 variants (Pro and Max) have already reached the highest class, and any M4 Ultra would reach far above the top of the chart at 128 GHz.

Real-world performance will inevitably differ, and vary according to benchmark and app used for comparison. Although single-core performance has improved steadily, apps that only run in a single thread and can’t take advantage of multiple cores are likely to show little if any difference between variants in each family.

Game Mode is also of interest for those considering the two versions of the M4 Base, with 4 or 6 E cores. This is because that mode dedicates the E cores, together with the GPU, to the game being played. It’s likely that games that are more CPU-bound will perform significantly better on the six E cores of the 10-Core version of the iMac, which also comes with a 10-core GPU and four Thunderbolt 4 ports.

Memory and GPU

Memory bandwidth is also important, although for most apps we should assume that Apple’s engineers match that with likely demand from CPU, GPU, neural engine, and other parts of the chip. There will always be some threads that are more memory-bound, whose performance will be more dependant on memory bandwidth than CPU or GPU cores.

Although Apple claims successive improvements in GPU performance, the range in GPU cores has started at 8 and attained 32-40 in Max chips. Where the Max variants come into their own is support for multiple high-res displays, and challenging video editing and processing.

Thunderbolt and USB 3

The other big difference in these Macs is support for the new Thunderbolt 5 standard, available only in models with M4 Pro or M4 Max chips; Base variants still only support Thunderbolt 4. Although there are currently almost no Thunderbolt 5 peripherals available apart from an abundant supply of expensive cables, by the end of this year there should be at least one range of SSDs and one dock shipping.

As ever with claimed Thunderbolt performance, figures given don’t tell the whole story. Although both TB4 and USB4 claim ‘up to’ 40 Gb/s transfer rates, in practice external SSD performance is significantly different, with Thunderbolt topping out at about 3 GB/s and USB4 reaching up to 3.4 GB/s. In practice, TB5 won’t deliver the whole of its claimed maximum of 120 Gb/s to a single storage device, and current reports are that will only achieve disk transfers at 6 GB/s, or twice TB4. However, in use that’s close to the expected performance of internal SSDs in Apple silicon Macs, and should make booting from a TB5 external SSD almost indistinguishable in terms of speed.

As far as external ports go, this widens the gap between the M4 Pro Mac mini’s three TB5 ports, which should now deliver 3.4 GB/s over USB4 or 6 GB/s over TB5, and its two USB-C ports that are still restricted to USB 3.2 Gen 2 at 10 Gb/s, equating to 1 GB/s, the same as in M1 models from four years ago.

My choice

With a couple of T2 Macs and a MacBook Pro M3 Pro, I’ve been looking to replace my original Mac Studio M1 Max. As it looks likely that an M4 version of the Studio won’t be announced until well into next year, I’m taking the opportunity to shrink its already modest size to that of a new Mac mini. What better choice than an M4 Pro with 10 P and 4 E cores and a 20-core GPU, and the optional 10 Gb Ethernet? I seldom use the fourth Thunderbolt port on the Studio, and have already ordered a Kensington dock to deliver three TB5 ports from one on the Mac, and I’m sure it will drive my Studio Display every bit as well as the Studio has done.

If you have also been tempted by one of the new Mac minis, I was astonished to discover that three-year AppleCare+ for it costs less than £100, that’s two-thirds of the price that I pay each year for AppleCare+ on my MacBook Pro.

I look forward to diving deep into both my new Mac and Thunderbolt 5 in the coming weeks.