Which M4 chip and model?

In the light of recent news, you might now be wondering whether you can afford to wait until next year in the hope that Apple then releases the M4 Mac of your dreams. To help guide you in your decision-making, this article explains what chip options are available in this month’s new M4 models, and how to choose between them.

CPU core types

Intel CPUs in modern Macs have several cores, all of them identical. Whether your Mac is running a background task like indexing for Spotlight, or running code for a time-critical user task, code is run across any of the available cores. In an Apple silicon chip like those in the M4 family, background tasks are normally constrained to efficiency (E) cores, leaving the performance (P) cores for your apps and other pressing user tasks. This brings significant energy economy for background tasks, and keeps your Mac more responsive to your demands.

Some tasks are normally constrained to run only on E cores. These include scheduled background tasks like Spotlight indexing, Time Machine backups, and some encoding of media. Game Mode is perhaps a more surprising E core user, as explained below.

Most user tasks are run preferentially on P cores, when they’re available. When there are more high-priority threads to be run than there are available P cores, then macOS will normally send them to be run on E cores instead. This also applies to threads running a Virtual Machine (VM) using lightweight virtualisation, whose threads will be preferentially scheduled on P cores when they’re available, even when code being run in the VM would normally be allocated to E cores.

macOS also controls the clock speed or frequency of cores. For background tasks running on E cores, their frequency is normally held relatively low, for best energy efficiency. When high-priority threads overspill onto E cores, they’re normally run at higher frequency, which is less energy-efficient but brings their performance closer to that of a P core. macOS goes to great lengths to schedule threads and control core frequencies to strike the best balance between energy efficiency and performance.

Unfortunately, it’s normally hard to see effects of frequency in apps like Activity Monitor. Its CPU % figures only show the percentage of cycles that are used for processing, and make no allowance for core frequency. It will therefore show a background thread running at low frequency but 100%, the same as a thread overspilt from P cores running at the maximum frequency of that E core. So when you see Spotlight indexing apparently taking 200% of CPU % on your Mac’s E cores, that might only be a small fraction of their maximum capacity if they were running at maximum frequency.

There are no differences between chips in the M4 family when it comes to each type of CPU core: each P core in a Base variant is the same as each in an M4 Pro or Max, with the same maximum frequency, and the same applies to E cores. macOS also allocates threads to different types of core using the same rules, and their frequencies are controlled the same as well. What differs between them is the number of each type of core, ranging from 4 P and 4 E in the 8-core variant of the Base M4, up to 12 P and 4 E in the 16-core variant of the M4 Max. Thus, their single-core benchmark results should be almost identical, although their multi-core results should vary according to the number of cores.

Game Mode

This mode is an exception to normal CPU and GPU core use, as it:

gives preferential access to the E cores,

gives highest priority access to the GPU,

uses low-latency Bluetooth modes for input controllers and audio output.

However, my previous testing didn’t demonstrate that apps running in Game Mode were given exclusive access to E cores. But for gamers, it now appears that the more E cores, the better.

GPU cores

These are also used for tasks other than graphics, such as some of the more demanding calculations required for Machine Learning and AI. However, experience so far with Writing Tools in Sequoia 15.1 is that macOS currently offloads their heavy lifting to be run off-device in one of Apple’s dedicated servers. Although having plenty of GPU cores might well be valuable for non-graphics purposes in the future, for now there seems little advantage for many.

Thunderbolt 5

M4 Pro and Max, but not Base variants, come equipped with Thunderbolt ports that not only support Thunderbolt 3 and 4, but 5, as well as USB4. Thunderbolt 5 should effectively double the speed of connected TB5 SSDs, but to see that benefit, you’ll need to buy a TB5 SSD. Not only are they more expensive than TB3/4 models, but at present I know of only one range that’s due to ship this year. There will also be other peripherals with TB5 support, including at least one dock and one hub, although neither is available yet. The only TB5 accessories that are already available are cables, and even they are expensive.

TB5 also brings increased video bandwidth and support for DisplayPort 2.1, although even the M4 Max can’t make full use of that. If you’re looking to drive a combination of high-res displays, consult Apple’s Tech Specs carefully, as they’re complicated.

Although TB5 will become increasingly important over the next few years, TB3/4 and USB4 are far from dead yet and are supported by all M4 models.

Which M4 chip?

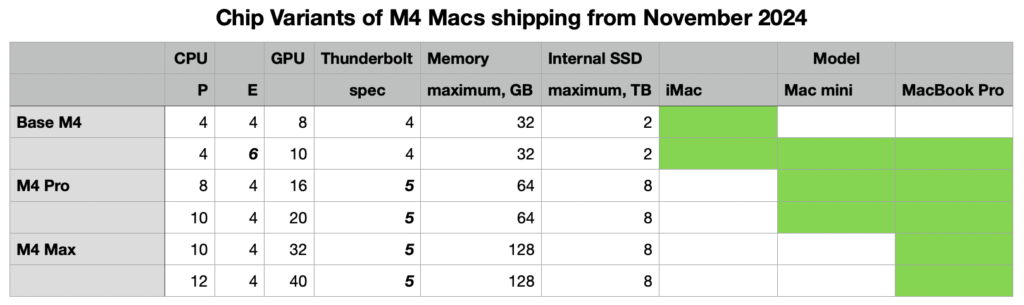

The table below summarises key figures for each of the variants in the M4 family that have now been released. It’s likely that next year Apple will release an Ultra, consisting of two M4 Max chips joined in tandem, in case you feel the burning desire for 24 P and 8 E cores.

Models available next week featuring each M4 chip are shown with green rectangles at the right.

There are two variants of the Base M4, one with 4P + 4E and 8 GPU cores, the same as Base variants in M1 to M3 families. There’s also the more capable variant, for the first time with 4P + 6E, which promises to be a better all-rounder, and when in Game Mode. It also has an extra couple of GPU cores.

The M4 Pro also comes in two variants, this time differing in the number of P cores, 8 or 10, and GPU cores, 16 or 20. Those overlap with the M4 Max, with 10 or 12 P cores and 32 or 40 GPU cores. Thus the gap between M4 Pro and Max isn’t as great as in the M3, with the GPUs in the M4 Max being aimed more at those working with high-res video, for instance. For more general use, there’s little difference between the 14-core Pro and Max.

Memory and storage

Chips in the M4 family also determine the maximum memory and internal SSD capacity. Apple has at last eliminated base models with only 8 GB of memory, and all now start with at least 16 GB. Base M4 chips are limited to a maximum of 32 GB, while the M4 Pro can go up to 64 GB, and the Max 128 GB.

Unfortunately, Apple hasn’t increased the minimum size of internal SSD, which remains at 256 GB for some base models. Smaller SSDs may be cheaper, but they are also likely to have shorter lives, as under heavy use their small number of blocks will be erased for reuse more frequently. That may shorten their life expectancy to much less than the normal period of up to 10 years, as was seen in some of the first M1 models. This is more likely to occur when swap space is regularly used for virtual memory. I for one would have preferred 512 GB as a starting point.

While Base M4 chips come with SSDs up to 2 TB in size, both Pro and Max can be supplied with internal SSDs of up to 8 TB.

I hope this proves useful in guiding your decision.