A brief history of Mac batteries

Before Apple launched the Macintosh Portable in September 1989, the only way to lug a Mac around was in a hefty case. Although it broke new ground, unless you enjoyed weight-training the Portable’s 7.2 kg mass wasn’t at all convenient. Some of that weight and bulk resulted from its internal lead-acid battery, which Apple claimed was capable of providing its power for 6-12 hours. In practice, unless you flew supersonic on Concorde, it wasn’t likely to last a transatlantic flight.

Two years later, Apple replaced that with PowerBook 100, 140 and 170 Macs, the first that were truly laptops rather than just luggables. Although the 100 still relied on a lead-acid battery, the 140 and 170 introduced 2.5 amp-hour NiCads. This was also the start of much confusion among users over battery care.

Lead-acid batteries live longest when kept fairly fully charged, and like to be trickle-charged whenever possible. At the time, conventional wisdom was that nickel-cadmium (NiCad) batteries were prone to a ‘memory effect’ whereby repeated charge-discharge cycles would somehow result in falling charge capacity until the battery was incapable of delivering any useful working time. As a result, users resorted to all kinds of magic tricks to try to maintain their 2-3 hour battery endurance, the period they could run off battery alone. While these new PowerBooks were less than half the weight of the original Portable, their useful working time on battery was still insufficient for many internal flights within the US or Europe.

In 1992, Apple started introducing new PowerBook models featuring the next generation of batteries, nickel-metal hydride or NiMH, pushing their endurance to as long as 6 hours if you were lucky. Their charge and use characteristics were different from NiCads and lead-acid, and although Apple provided battery management software, many seemed to distrust it and preferred their own routines. Given that at this time a PowerBook could have any of five different battery types (as there were Type I, II and III NiMH), some confusion was inevitable.

This proved just the right market for expensive battery conditioners, aimed at organisations with many PowerBooks, and costing significantly less than all the replacement batteries they claimed to save. To this day I don’t know whether any of their proprietary charge-discharge sequences ever improved either endurance or overall working life, but they seemed a good idea at the time. The PowerBook 520 of May 1994 supported one or two “Intelligent” NiMH batteries with a claimed endurance of up to 5 hours each, and had at last reached the capacity needed to operate a Mac for the duration of a transatlantic flight, so long as you went no further than the East Coast.

Just over a year later, in the PowerBook 190cs, Apple brought the first of the new generation with lithium ion batteries, although in that case it resulted in a small reduction in endurance compared with the NiMH battery in the 190. From 1997. LiIon became standard for almost all the remaining PowerBook models until 2006, when the first MacBook Pro with its shiny new Intel Core Duo processor also brought lithium-polymer, as used today.

Battery capacities had been rising slowly, and that MacBook Pro’s battery provided 60 watt-hours, giving an endurance of ‘up to’ 4.5 hours on a full charge. For the first time, Apple felt confident enough to forecast the working life of a maximum (that ‘up to’ again) of 300 charge cycles.

In the years since, battery capacity has increased further, as has endurance. For example, the 17-inch MacBook Pro from early 2009 had a 95 watt-hour lithium polymer battery claimed to run for ‘up to’ 8 hours from a full charge, and to have a working life of a maximum of 1,000 cycles.

Users were provided with basic power management features in the Energy Saver pane in System Preferences.

There was also an active market in third-party monitoring and management software, here Battery Health Monitor from Sonora Graphics.

This is Energy Saver a couple of years later, in 2011.

This shows the Energy Saver pane, detailed information in System Information, and another third-party utility, coconutBattery Plus by Coconut-Flavour, in 2020.

The next big step up came not with better batteries, but in 2020 with the switch from Intel CPUs to Apple silicon chips. The following year, the 16-inch MacBook Pro with a capacity of nearly 8.7 amp-hours (99.6 watt-hours) was claimed to run for up to 14 hours browsing over Wi-Fi, with the same 1,000 cycle battery working life.

The chart above shows how capacity, expressed here in watt-hours, has increased in major new PowerBook and MacBook Pro models over this period. The most substantial increases occurred in 1997-98 and 2007-08, coinciding with the introduction of LiIon batteries and Intel MacBook Pros.

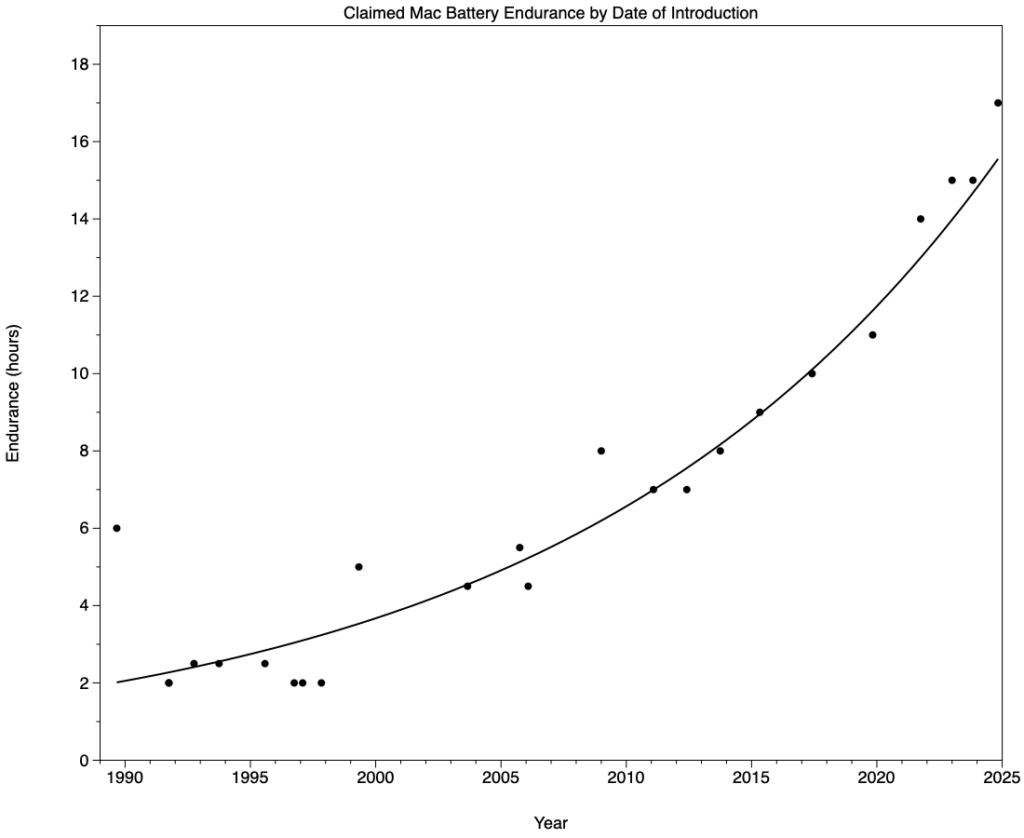

Claimed endurance on a fully-charged battery has risen exponentially over time, but I doubt whether that will be sustained for much longer.

As you might expect, there’s also a looser non-linear relationship between battery capacity and claimed endurance, although that has altered with the transition to low-power Apple silicon chips.

As many have discovered, even using battery management software in macOS, some batteries die young, and others can swell alarmingly. Over this period of 35 years, Apple has operated various extended battery support schemes, and faced criticism over battery working life. Some have even alleged that battery replacement is a profitable service for Apple. But in the long run, many of us have made increasing use of battery-powered Macs, and they have transformed many lives.