Urban Revolutionaries: 1 Leaving the country

Had there been opinion pollsters during the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, no doubt we would have a good idea of the three most popular reasons for moving from the country to towns and cities. Evidence from paintings isn’t always reliable, and depends on the artist’s opinion. However, there are several good indications that I’ll consider here.

Perhaps the most detailed account appears in the many clues in William Hogarth’s opening image in his series A Harlot’s Progress. Sadly, some may have been lost when his original paintings were destroyed by fire in 1755, forcing us to rely on the engravings made of them.

William Hogarth (1697–1764), A Harlot’s Progress: 1 Ensnared by a Procuress (engraving 1732 after painting c 1731), engraving, 30.8 x 38.1 cm, British Museum, London. Wikimedia Commons.

Moll Hackabout, who is about to start her downfall as a harlot, is dressed in her Sunday best, with a fine bonnet and white dress to signify that she’s an innocent country girl. In Moll’s luggage is a symbolic dead goose, suggesting her death from gullibility. The address on a label attached to the dead goose reads “My lofing cosen in Tems Stret in London” (‘My loving cousin in Thames Street in London’), implying that Moll’s move to London has been arranged through intermediaries, who will have profited from her being trafficked into the hands of Elizabeth Needham, a notorious brothel-keeper and madame.

Hogarth thus presents Moll as a gullible victim of human trafficking to supply country-fresh prostitutes for London. Although he did paint a companion series to A Harlot’s Progress involving a man, he didn’t come from the country, so Hogarth sheds no light on the reasons for men and families moving from the country into cities, a theme that doesn’t appear to have been tackled in well-known paintings.

John Roddam Spencer Stanhope (1829–1908), Robin of Modern Times (1860), oil on canvas, 48.3 x 85.7 cm, Private collection. Wikimedia Commons.

John Roddam Spencer Stanhope’s Robin of Modern Times (1860) is a wide-angle composition set in the rolling countryside of southern England, during the summer. The foreground is filled with a young woman, who is asleep on a grassy bank, her legs akimbo. She wears cheap, bright red beads strung on a necklace, and a floral crown fashioned from daisies is in her right hand. She wears a deep blue dress, with a black cape over it, and the white lace of her petticoat appears just above her left knee. On her feet are bright red socks and black working/walking boots. A couple of small birds are by her, one a red-breasted robin, and there are two rosy apples near her face. In the middle distance, behind the woman’s head, white washing hangs to dry in a small copse. A farm labourer is working with horses in a field, and at the right is a distant farmhouse. This most probably refers to the continuing account of how girls and young women from the country around London found their way to the city to become its prostitutes.

There were other more prosaic reasons that younger people migrated. Among them was a long period of harsh weather, the Little Ice Age, that lasted until the late nineteenth century.

George Morland (1763–1804), Winter Landscape with Figures (c 1785), oil on canvas, 72.4 x 92.7 cm, Yale Center for British Art, New Haven, CT. Wikimedia Commons.

Many British winters featured deep and prolonged snow, even in the south of the country, as shown so well in George Morland’s Winter Landscape with Figures from about 1785. This period was hard enough in towns and cities, but many farms and villages in the country remained isolated for weeks at a time. Even when there wasn’t snow on the ground, there were prolonged droughts and widespread crop failure.

Over this period, staple crops were also changing, with the rising popularity of the potato. Just as rural populations were becoming dependent on the potato, they were struck by the mould causing blight, in 1845. Within a year, much of Europe was suffering failure of the potato crop, leading to death from starvation in about one million in the Great Irish Famine, together with fewer deaths in Scotland and the rest of Europe.

Jules Bastien-Lepage (1848–1884), October: Potato Gatherers (1878), oil on canvas, 180.7 x 196 cm, National Gallery of Victoria, Melbourne. Wikimedia Commons.

Jules Bastien-Lepage shows the autumn harvest in a more successful year in his October: Potato Gatherers from 1878.

Another sustained pressure on those living in the country was the effect of land enclosure from 1500-1900.

John Crome (1768–1821), Mousehold Heath, Norwich (c 1818-20), oil on canvas, 109.9 x 181 cm, The Tate Gallery (Purchased 1863), London. © The Tate Gallery and Photographic Rights © Tate (2021), CC-BY-NC-ND 3.0 (Unported), https://www.tate.org.uk/art/artworks/crome-mousehold-heath-norwich-n00689

John Crome’s Mousehold Heath, Norwich (c 1818-20) shows the low rolling land to the north-east of the city that had remained open heath and common land until the late eighteenth century. By 1810, much of it had been enclosed and ploughed up for agriculture. Crome opposed the enclosure of common land, and here shows the rich flora and free grazing provided. In the right distance some of the newly created farmland is visible as a contrast.

Enclosure concentrated productive land in the hands of those who owned it, and locked out the poorer labourers who had been reliant on common grazing.

While Britain was spared, across much of Europe the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries saw a succession of wars fought largely in the country. Advancing and retreating armies seized what food they could from farms, and often burned and destroyed what they couldn’t remove.

Horace Vernet (1789–1863), The Campaign in France (1814), oil on canvas, dimensions not known, location not known. Wikimedia Commons.

Once Napoleon’s armies had been defeated at Leipzig in 1813, those of the other countries in Europe pursued them into north-east France, where there was a series of smaller battles and skirmishes fought in the French countryside, amid the terrified farmers and their families. Here Horace Vernet shows soldiers fighting around a burning farmhouse, as its occupants try to escape with little more than their lives. Their cattle are panicking, and it appears that the farmer himself has been shot, perhaps when trying to defend his family. A small boy buries his head into his mother’s apron.

As a result of those pressures, whole families abandoned their relatives, often those who were older and less likely to make a successful living in the city, and went to live in the growing towns and cities.

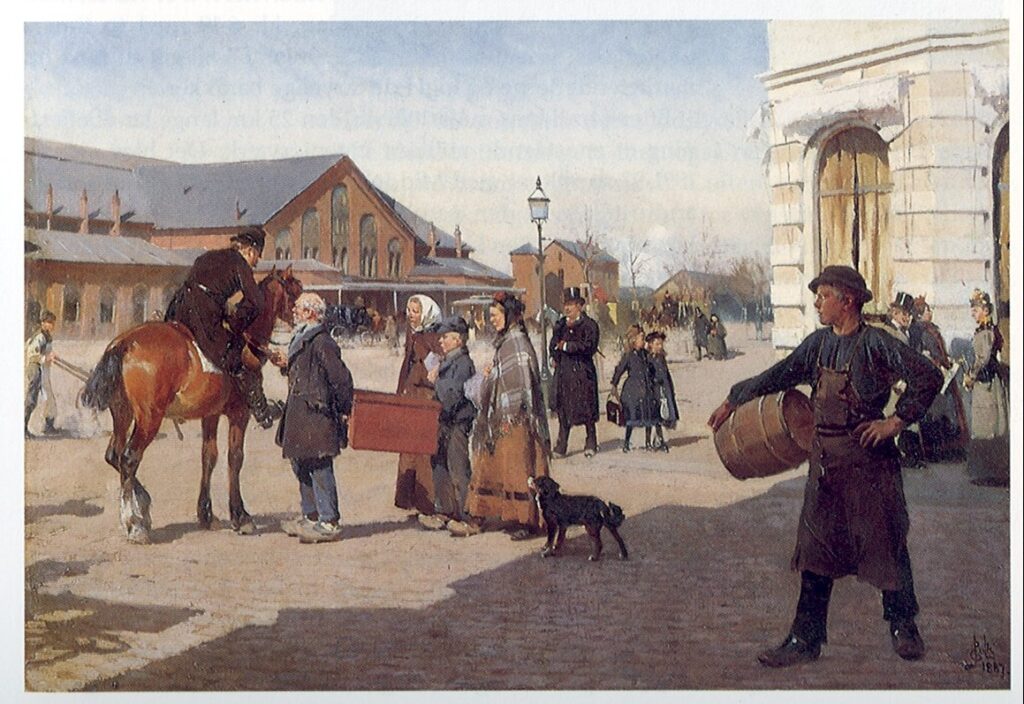

Erik Henningsen (1855–1930), Farmers in the Capital (1887), oil, further details not known. Wikimedia Commons.

Erik Henningsen’s painted record of Farmers in the Capital from 1887 is one of few contemporary accounts. This family group consists of an older man, the head of household, two younger women, and a young boy. Everyone else is wearing smart leather shoes or boots, but these four are still wearing filthy wooden clogs, with tattered and patched clothing. The two men are carrying a large chest containing the family’s worldly goods, and beside them is their farm dog. The father is speaking to a mounted policeman, presumably asking him for directions to their lodgings.

The large brick building in the background is the second version of Copenhagen’s main railway station, opened in 1864, and replaced by the modern station in 1911. This demonstrates another significant factor in the attraction of people to towns and cities: the spread of railways across Europe.