Last Week on My Mac: A brief history of what we take for granted

Yesterday’s brief history of ColorSync was one of the most interesting in this series to research. In most cases, these brief histories cover well-trodden ground, with several previous accounts to provide a framework for my collection of screenshots and personal experience. On this occasion, even Wikipedia was vague and brief. Yet at the time ColorSync’s role was of great importance, as faithful colour reproduction was so essential to the creatives and businesses that relied on Macs.

It’s also a richly multi-disciplinary field, drawing on neurophysiology, physics, colour science and perceptual psychology. Key concepts like the modelling of colour appearance have grown into lengthy and highly technical books, several of which I seem to have collected over the years. They also provide absorbing accounts of the lengthy journey over several centuries to bring basics such as colour order systems.

Franciscus Aguilonius (François d’Aguilon) (1567-1617), RYB Colour Scheme (1613), https://books.google.com/books?id=Y2BDAAAAcAAJ&pg=PA40#v=onepage&q&f=false Wikimedia Commons.

In 1615, the Flemish physicist Franciscus Aguilonius, also known as François d’Aguilon, (1567-1617) was the first to propose a colour line extending from white (albus) to black (niger), passing through the primaries of yellow (flavus), red (rubeus), and blue (caeruleus). Below that are secondary combinations of orange (aureus) and purple (purpureus), with green (viridis). This was published in his six volume treatise on optics, whose title page and illustrations were designed by Peter Paul Rubens.

The Munsell color system. Image © 2007, Jacob Rus, via Wikimedia Commons.

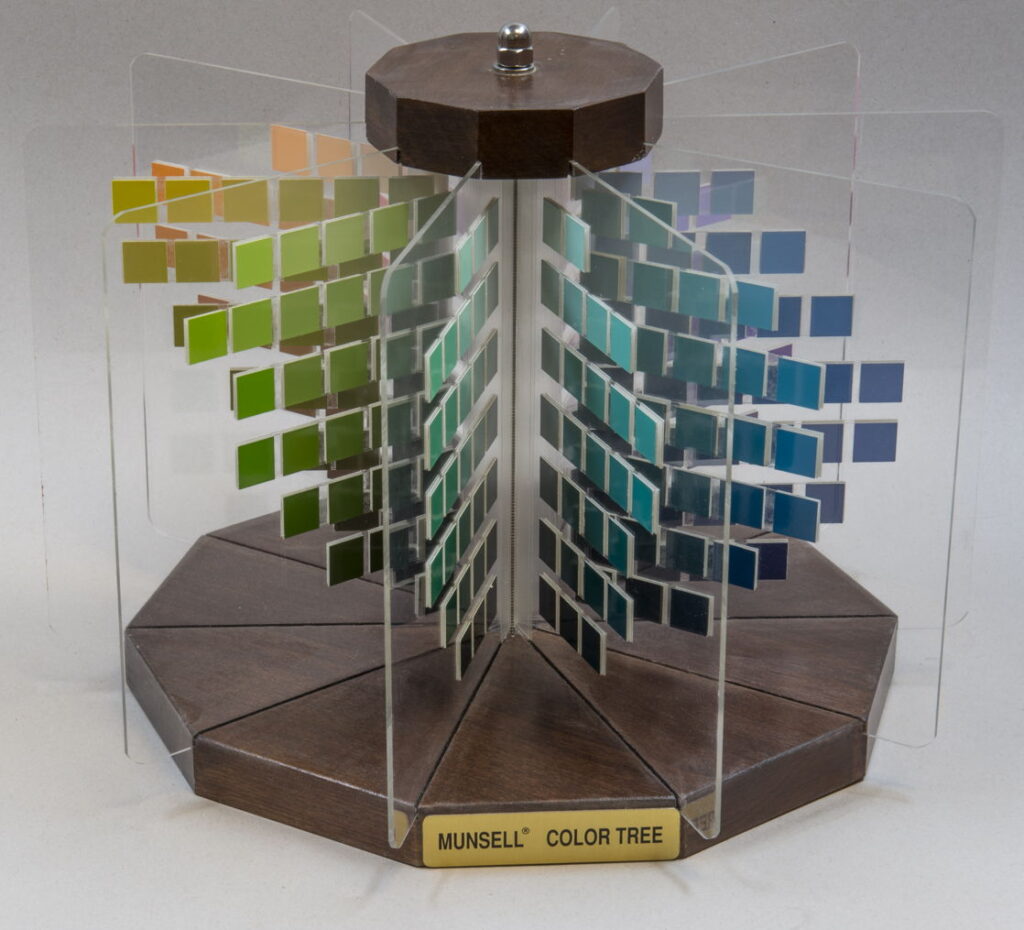

In the early twentieth century, Albert Henry Munsell (1858-1918) devised a system closer to those used to specify colour today. This shows the circle of ten hues, here displayed with values of 5 and chromas of 6. The vertical value scale ranging from 0 to 10 is shown in neutral colours, from black to white. A wedge of constant 5PB hue is then shown at a fixed value of 5, the chromas ranging from 0 (grey) to 12 (pure colour).

Pantone Inc., Pantone Swatches (2015), Image by Céréales Killer, processed by MagentaGreen, via Wikimedia Commons.

Contemporary designers are also familiar with the Pantone System of swatches of standardised colours, that have become standards in several sectors such as process colour printing.

The problem tackled by ColorSync is that no device used with computers can represent the full range of colours, each having its own range or gamut. For colour to appear consistent in the image captured by a scanner or camera, on the display used to adjust settings such as white point and balance, and in the final printed page, colours have to be adjusted or mapped to look right on that device. To do that each device has its own colour profile, and a colour management system adjusts colours on each according to the desired quality and goals of the operator.

Most of the principles involved were known before the arrival of Macs. But when Apple, Adobe, Agfa, Microsoft, Kodak, Silicon Graphics, Sun and Taligent (an Apple-IBM partnership) sat down together in 1993 as the International Colour Consortium, they had a lot of work to do before photographers and designers could have confidence that their work would survive the journey into print retaining what appeared to be faithful colour.

ColorSync and colour management is but one example of the broad range of fields that form the basis of what we do on our Macs, from floating point computation to Unicode text. With the marketing drive to sell modern computers as appliances, we have lost sight of what goes into them. Just as with transport history, our view of what happened is largely superficial and limited to the tangible in collections of hardware.

This misleads us into thinking that today’s Artificial Intelligence is somehow capable of replacing human research and discovery when all it can really do is rehash what we have created in the past. If any of today’s much-vaunted large language models could have started to tackle the problems addressed by ColorSync during the 1990s, do you seriously think that they would have come up with the solutions embedded in Mac OS X less than a decade later? For without prior knowledge won by humans, we’d still be wrestling with the number of rs in the word strawberry.

Let’s celebrate human achievement and empower that instead.