Paintings of Saint-Tropez: Colour, boats and bathers 1

This weekend, I invite you to join me in the fishing village of Saint-Tropez, where we’ll escape the winter blues in the warm light of paintings from the turn of the nineteenth to twentieth centuries. With today’s super-yachts and tourists it might not seem much of a village now, but its population has changed little over the last two hundred years and remains around four thousand.

Saint-Tropez is unusual for a port on the north coast of the Mediterranean as it faces north, being on the south side of a deep bay, the Gulf of Saint-Tropez, and lies midway between Toulon and Cannes. Towering above the east of the old port with its sheltered harbour is its Citadel. There never was a Saint Tropez, but the village owes its name to a legendary martyr Saint Torpes of Pisa whose body is supposed to have reached this location in a rotten boat.

Like much of the coast around here, Saint-Tropez had a generally quiet life supporting its small fishing fleet until the railway came in the latter half of the nineteenth century. The main line to Marseille was completed in 1856, and by the 1880s regular express services transported folk from Paris at speed and in comfort. Like most of the better resorts along this section of the Côte d’Azur, Saint-Tropez requires you to travel an extra few miles from the nearest railway station, but that proved no deterrent to artists fleeing Paris for the summer.

Among the first was Paul Signac, who spent early May 1892 in Saint-Tropez, where he rented a cottage in the old town, and announced his intended marriage to Berthe Roblès.

Paul Signac (1863-1935), Soleil couchant sur la ville (étude) (1892), oil on wood, 15.5 x 25 cm, Private collection. Wikimedia Commons.

Sunset over the Town is an oil study Signac painted on wood in 1892, which appears Fauvist in the intensity of its colours. It shows a view of Saint-Tropez that he turned into a finished Divisionist painting, as well as producing another sketch in Conté crayon, and an unusual drawing in watercolour and ink that is reminiscent of van Gogh, and prescient of his later watercolours.

Paul Signac (1863-1935), Le Port au soleil couchant, Opus 236 (Saint-Tropez) (Op 236) (1892), oil on canvas, 65 x 81.3 cm, Private collection. Wikimedia Commons.

During this short stay in Saint-Tropez, Signac painted its harbour from several different angles. The Port at Sunset, Opus 236 (Saint-Tropez) (1892) is one of the most successful of these, with its echoes of his earlier paintings of Concarneau.

Paul Signac (1863-1935), The Bonaventure Pine (Op 239) (1893), oil on canvas, 65.7 x 81 cm, Museum of Fine Arts, Houston, TX. Wikimedia Commons.

While exploring Saint-Tropez during his return the following year, Signac came across a huge umbrella pine tree by the villa of a certain Monsieur Bonaventure, which he painted as The Bonaventure Pine.

Paul Signac (1863-1935), Tartanes pavoisées (Sailing Boats in Saint-Tropez Harbour) (Op 240) (1893), oil on canvas, 56 x 46 cm, Von der Heydt Museum, Wuppertal, Germany. Wikimedia Commons.

Signac’s original title for this painting is Tartanes pavoisées, which translates loosely as Fishing Boats Dressed Overall. He painted three studies for this, to get its triangular composition right, and seems to have been pleased with the result, exhibiting it regularly. Two years later, he traded it for a bicycle, and in 1910 it became his first painting to enter a public collection, in Wuppertal, Germany.

Tartanes are vernacular fishing boats from this section of the Mediterranean coast, with a single mast bearing a lateen sail.

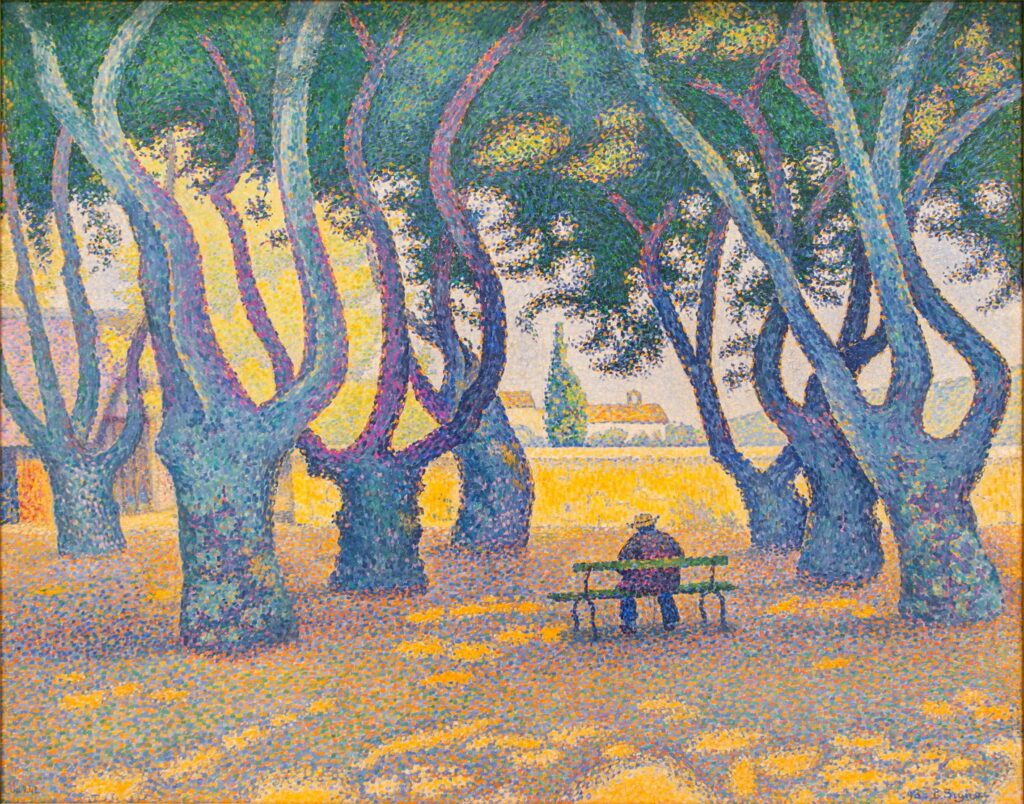

Paul Signac (1863-1935), Les Plantanes (Place des Lices, Saint-Tropez) (Plane Trees) (Op 242) (1893), oil on canvas, 65.4 x 81.9 cm, Carnegie Museum of Art, Pittsburgh, PA. Image by Photolitherland, via Wikimedia Commons.

Later that year, and continuing his theme of trees, he painted these Plane Trees in the Place des Lices in the centre of Saint-Tropez. Instead of showing the boules players who frequented this area, he shows an old man sitting on a bench in great serenity.

Paul Signac (1863-1935), Harbour (1894), further details not known. Wikimedia Commons.

Harbour (1894) is another of Signac’s many views of the harbour that he painted while he stayed there, leading to finished oil paintings such as his Red Buoy below.

Paul Signac (1863-1935), Saint-Tropez. The Red Buoy (Cachin 284) (1895), oil on canvas, 81 x 65 cm, Musée d’Orsay, Paris. Wikimedia Commons.

Signac recorded in his journal that he started painting Saint-Tropez. The Red Buoy on 22 August 1895. It shows the Quai Jean-Jaurès behind the richly coloured reflections of those buildings, with a colour scheme dominated by the blue of the water, its complementary vermilion sail and buoy, and the pale orange of the buildings and their reflections. Signac developed the composition and colour harmonies during the summer of 1895 before starting this final version, which was exhibited to acclaim over the following two years.

At the end of 1897, Signac and his wife bought a house in Saint-Tropez and took up residence there. In the same year, his friend Théo van Rysselberghe moved to Paris, but had already started visiting the Côte d’Azur.

Théo van Rysselberghe (1862–1926), Pointe Saint-Pierre, Saint-Tropez (1896), oil on canvas, 78 x 98 cm, Musée Nationale d’Histoire et d’Art du Grand-duché de Luxembourg, Luxembourg. WikiArt.

In Pointe Saint-Pierre, Saint-Tropez (1896) van Rysselberghe uses traditional anatomical technique to model these pines in the hot light of the Mediterranean coast. Their structure is explicit, each tree assembled from its hundreds of small marks laid along branches, then giving rise to foliage. This point is to the east of the old port.

Théo van Rysselberghe (1862-1926), l’Heure embrasée (Provence) (The Glowing Hour (Provence)) (1897), oil on canvas, 228 x 329 cm, Staatliche Kunstsammlungen, Weimar. WikiArt.

The following year, van Rysselberghe was one of the first to depict bathers near Saint-Tropez in his aptly named Glowing Hour (Provence).