Napoleons of paintings: 1 Victories

The most famous French person, born a Corsican of Italian origin, who died on the British South Atlantic island of Saint Helena, was the Emperor Napoleon I. His life, battles, wives and descendants have been painted repeatedly by some of the great artists of the nineteenth century, from Girodet to JMW Turner. This weekend I show a few of those images of greatness and downfall.

Napoleon Bonaparte rose rapidly through the French army following the French Revolution of 1789, until he became its commander for the campaign against Austria and Italy in 1796.

Georges Clairin (1843–1919), Napoleon’s Troops in Front of San Marco, Venice (date not known), oil on canvas, dimensions and location not known. The Athenaeum.

About a century later, Georges Clairin’s painting of Napoleon’s Troops in Front of San Marco, Venice provides a biased gloss on the fall of the Venetian Republic to Napoleon Bonaparte in 1797. The French occupation around 4 June may itself have been relatively peaceful, but by the end of July had been declared a siege, with the arrest and imprisonment of many Venetians. Later in the year, the French plundered the city of many of its artworks, something that Clairin seems to have overlooked.

As a national hero, Napoleon and his army travelled on to invade Egypt and Syria in 1798.

Pierre-Narcisse Guérin (1774–1833), Napoleon Bonaparte Pardoning the Rebels at Cairo, 23rd October 1798 (1808), oil on canvas, 365 × 500 cm, Château de Versailles, Versailles, France. Wikimedia Commons.

In 1806, Napoleon commissioned Pierre-Narcisse Guérin to paint for the Gallery of Diana in the Tuileries Palace. The result was Napoleon Bonaparte Pardoning the Rebels at Cairo, 23rd October 1798, completed in 1808.

Napoleon had taken the French army into Egypt in 1798, and conquered Alexandria and Cairo. On 21 October, the citizens of Cairo organised an uprising, and murdered the French commander and Napoleon’s aide-de-camp. The French fought back with artillery, then the cavalry fought their way back into the city, forcing the rebels out into the desert, or into the Great Mosque. Napoleon brought his artillery to bear on the mosque, following which his troops stormed the building, killing or wounding over five thousand. With control restored over Cairo, the leaders of the revolt were hunted down and executed. Following this, the city was taxed heavily in punishment, and put under military rule.

Guérin’s painting shows a very different event, in which Napoleon is engaged in open discourse with the rebels. However, the presence of French cavalry behind the Egyptians, and the action taking place at the far right, suggests the truth behind this ‘pardon’.

Anne-Louis Girodet de Roussy-Trioson (1767–1824), The Revolt of Cairo (sketch) (1810), oil and India ink on paper mounted on canvas, 30.8 x 45.1 cm, Art Institute of Chicago, Chicago, IL. Wikimedia Commons.

In 1810, Girodet painted the only reasonably accurate account of The Revolt of Cairo of 21 October 1798 and Napoleon’s massacre of the city’s residents. Most were killed when French cannons fired at the Al-Azhar Mosque where they were seeking refuge. This is a late oil sketch for the finished painting.

Léon Cogniet (1794–1880), Bonaparte’s 1798 Egyptian Expedition (1835), ?fresco ceiling, dimensions not known, Musée du Louvre, Paris. Wikimedia Commons.

Léon Cogniet was also called to document Napoleon’s empire, painting his Bonaparte’s 1798 Egyptian Expedition (1835) on a ceiling in the Louvre Palace, as an explanation of how so many Egyptian artefacts came to be in Paris, ironically now on display in that same building.

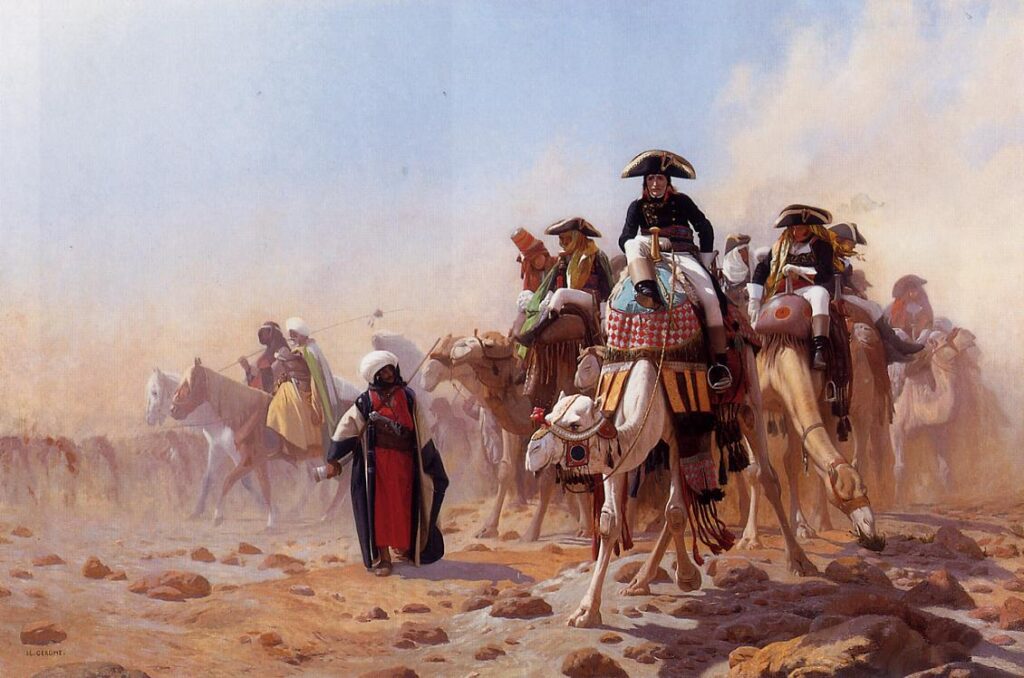

Jean-Léon Gérôme (1824–1904), General Bonaparte and his Staff in Egypt (1867), oil on canvas, 58.4 x 88.2 cm, Private collection. Wikimedia Commons.

Jean-Léon Gérôme made several paintings showing Napoleon in Egypt, including this highly detailed and intricate version of General Bonaparte and his Staff in Egypt from 1867.

In November 1799, Napoleon used these military victories to engineer a coup and became First Consul of the French Republic.

Paul Delaroche (1797–1856), Napoleon Crossing the Alps (1850), oil on canvas, 279.4 x 214.5 cm, Walker Art Gallery, Liverpool, England. Wikimedia Commons.

In early 1800, Napoleon made moves to reinforce French troops in Italy, so they could repossess territory lost to the Austrians in recent years. Leading his Reserve Army, he crossed the Alps via the Great St Bernard Pass in May, and his troops fought their first battle at Montebello on 9 June. Paul Delaroche was commissioned to paint a faithful account of this. His Napoleon Crossing the Alps from 1850 does at least sit the First Consul astride a mule, the only mount capable of carrying him in these conditions, but it’s still a good way from the truth. Napoleon’s face is bare, his left hand uncovered and resting on the pommel of his saddle, and he’s wearing a thin cloak and thin riding breeches.

In 1803, Napoleon sold the French territory of Louisiana to the United States, and at the end of the following year crowned himself Emperor of the French, giving him near-absolute power.

François Flameng (1856–1923), Napoleon hunting in the forest of Fontainebleau (date not known), further details not known. Wikimedia Commons.

Among the paintings of François Flameng showing the Napoleonic period, one of the most striking is this scene of Napoleon Hunting in the Forest of Fontainebleau, in which the pack is closing in on a cornered stag as the sun sets.

At about this time, Pierre-Paul Prud’hon’s paintings became appreciated by the emperor’s court, and Napoleon himself. He was thus commissioned to paint the Empress Joséphine. Marie Josèphe Rose Tascher de La Pagerie, as she was before marrying the Emperor in late 1804, must have been forty-one or forty-two years old at the time of Prud’hon’s commission, and a widow with two children. Most unconventionally, it must have been agreed that she wouldn’t be portrayed in her official role of Empress.

Pierre-Paul Prud’hon (1758–1823), Study for a Portrait of Empress Joséphine (1805), black chalk, stumped in some areas, heightened with white, on blue paper, ruled in pen and black ink, 24.8 x 30.2 cm, The Morgan Library & Museum, New York, NY. Wikimedia Commons.

Prud’hon’s black chalk Study for a Portrait of Empress Joséphine, from 1805, perhaps shows the original concept of the Empress in her role as patron of the arts, complete with a lyre, reclining on the coast, against a background of trees.

Pierre-Paul Prud’hon (1758–1823), The Empress Joséphine (c 1805), oil on canvas, 244 x 179 cm, Musée du Louvre, Paris. Wikimedia Commons.

His finished painting of The Empress Joséphine (c 1805) dispenses with the lyre and seats her on a stone bench in woodland, looking pensive if not slightly wistful.

But Joséphine failed to become pregnant by Napoleon, and four years later he informed her that he had to find a wife who could provide him with an heir.