Commemorating the centenary of John Singer Sargent’s death: 1 Pupil

In the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, there were three dominant painters who flirted with Impressionism but retained conventional styles: Anders Zorn from Sweden, Joaquín Sorolla from Spain, and John Singer Sargent, an American expatriate who worked from studios in Paris and London. All three died in the 1920s, and this year we commemorate the centenary of Sargent’s death on 14 April 1925. This is the first in a series of six articles outlining his career with but a small and personal selection of his paintings.

Sargent was born to American expatriate parents in Florence, Italy, in 1856. He was educated at home and showed early skill in drawing. Already competent in watercolour at the age of 14, he saw many of the works of the great Masters during travels around Europe with his family. In 1874 he succeeded in gaining admission to the École des Beaux-Arts in Paris, where he was taught mainly by Carolus-Duran, and less by Léon Bonnat.

Although his initial enthusiasm was for landscapes, Carolus-Duran encouraged him towards portraiture, and his first significant portrait was accepted by the Salon in 1877. His talent was recognised by the critics, and he made friends with Julian Alden Weir and Paul César Helleu, who in turn introduced him to other leading artists of the day, including Degas, Rodin, Monet, and Whistler.

John Singer Sargent (1856-1925), Fishing for Oysters at Cançale (1878), oil on canvas, 41 x 61 cm, Museum of Fine Arts, Boston. WikiArt.

Sargent’s early style was realist, particularly in portraiture, and leaned towards Impressionism as seen in this painting of Fishing for Oysters at Cançale from 1878, but was quite distinct from the work of the leading Impressionists at that time. In the summer of 1878, John Singer Sargent had just completed his studies with Carolus-Duran, and went off on a working holiday to Capri, staying in the village of Anacapri, as was popular with other artists at the time.

Capri was still quite a select holiday destination then, and unspoilt. But getting a local model was tricky, because of the warnings that women were given by priests. History has proved those priests only too right in their advice. One young local woman, Rosina Ferrara, seemed happy to pose for him, though. She was only 17, and Sargent a mere 22 and just developing his skills in portraiture. Over the course of that summer, Sargent painted at least a dozen works featuring young Rosina, who seems to have become almost an obsession with him.

John Singer Sargent (1856–1925), Capri Girl (Dans les Oliviers, à Capri) (1878), oil on canvas, 77.5 x 63.5 cm, Private collection. The Athenaeum.

One, Dans les Oliviers, à Capri, above, he exhibited at the Salon the following year. A near-identical copy A Capriote, below, he sent back for the annual exhibition of the Society of American Artists in New York, in March 1879. The latter is now in the Museum of Fine Arts in Boston.

John Singer Sargent (1856–1925), A Capriote (1878), oil on canvas, 76.8 x 63.2 cm, Museum of Fine Arts Boston, Boston, MA. Wikimedia Commons.

John Singer Sargent (1856–1925), View of Capri (c 1878), oil on cardboard, 26 x 33.9 cm, Yale University Art Gallery, New Haven, CT. Wikimedia Commons.

He also painted a pair of views of what was probably the roof of his hotel. In View of Capri, above, made on cardboard, Rosina stands looking away, her hands at her hips. In the other, Capri Girl on a Rooftop, below, she dances a tarantella to the beat of a friend’s tambourine. The latter painting Sargent dedicated “to my friend Fanny”, presumably Fanny Watts, who modelled for the first portrait that Sargent had exhibited at the Salon the previous year.

John Singer Sargent (1856–1925), Capri Girl on a Rooftop (1878), oil on canvas, 50.8 x 63.5 cm, Crystal Bridges Museum of American Art, Bentonville, AR. Wikimedia Commons.

John Singer Sargent (1856–1925), Portrait of Rosina Ferrara (1878), further details not known. Wikimedia Commons.

Rosina appears to have danced for Sargent again, for him to paint her in Portrait of Rosina Ferrara, above, as a precursor to his later paintings of Spanish dancers. But of all Sargent’s paintings of Rosina, the finest portrait, possibly one of the finest of all his ‘quick’ portraits from early in his career, is another painted in oils on cardboard: Rosina Ferrara, Head of a Capri Girl, below.

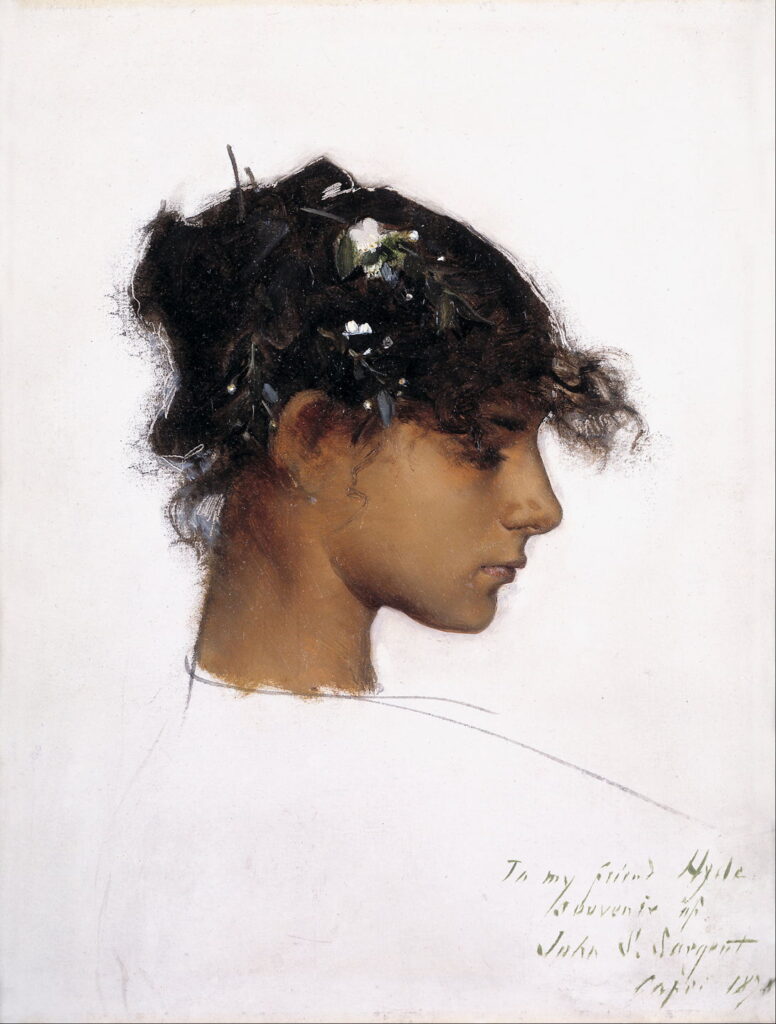

John Singer Sargent (1856–1925), Rosina Ferrara, Head of a Capri Girl (c 1878), oil on cardboard, 49.5 x 41.3 cm, Denver Art Museum, Denver, CO. Wikimedia Commons.

This he dedicated to “Hyde” (the artist Frank Hyde), and signed in 1878, while he was still on Capri. There are another couple of portraits he painted of a young woman during that summer on Capri. Although she’s in more serious mood, possibly even a little surly with ennui, I wonder if they also show Rosina Ferrara.

John Singer Sargent (1856–1925), Head of a Capri Girl 1 (1878), oil on canvas, 43.2 x 30.5 cm, Private collection. The Athenaeum.

John Singer Sargent (1856–1925), Head of a Capri Girl 2 (c 1878), oil on canvas, 47 x 38.1 cm, Private collection. The Athenaeum.

Sargent left Capri, eventually returning to Paris and his inexorable rise to greatness, fortune and success. But that wasn’t the end of Rosina’s modelling career, not by a long way. Frank Hyde, to whom Sargent had dedicated a portrait of her, painted his own version a couple of years later.

John Singer Sargent (1856–1925), Portrait of Carolus-Duran (1879), oil on canvas, 116.8 × 95.9 cm, Sterling and Francine Clark Art Institute, Williamstown, MA. Wikimedia Commons.

Sargent’s famous Portrait of Carolus-Duran (1879) is not only his personal tribute to his teacher, but when it was shown at the Salon proved the foundation of Sargent’s own career as a portraitist.

John Singer Sargent (1856–1925), Fumée d’ambre gris (Smoke of Ambergris) (1880), oil on canvas, 139.1 x 90.6 cm, Sterling and Francine Clark Art Institute, Williamstown, MA. WikiArt.

He continued to travel in Italy and Spain, where in 1880 he painted Smoke of Ambergris, demonstrating what was to come beyond mere portraits.