Reading Visual Art: 211 Narrative modes A

Telling a story, narrative, in a painting is one of its most common purposes, and greatest challenges. A landscape painting shows a view at a moment in time, but doesn’t normally tell a story, as that requires a minimum of two states, with the story linking them. So, although we might speculate what’s going in that countryside, without an indication of what went before, or what happened afterwards, there’s no story there.

Over the centuries, even millennia, since humans have been painting, several techniques have developed for telling a story with more than one timepoint shown in paintings. Although the terms used have varied, in general those fall into the following categories:

instantaneous, where the image is intended to show what was happening at a single moment in time, even though it’s likely to contain references to other moments in time;

multi-image, where a series of separate images (paintings) is used to tell the story;

multiplex, where a single image contains representations of two or more moments in time from a story;

multi-frame, where two or more picture frames are used to tell a story, as in comics or manga;

polymythic, where a single image contains two or more distinct stories.

In this article and tomorrow’s sequel, I show examples of each of these.

Instantaneous

Nicolas Poussin (1594–1665), Rinaldo and Armida (c 1630), oil on canvas, 82.2 x 109.2 cm, Dulwich Picture Gallery. Wikimedia Commons.

Nicolas Poussin’s Rinaldo and Armida from about 1630 draws its narrative from one of his favourite literary works, a then-popular epic poem by Torquato Tasso (1544-1595) titled Gerusalemme Liberata (Jerusalem Delivered), and published in 1581. I have written a series of fourteen articles showing paintings and telling its story, which start here. This particular episode is detailed here.

The sleeping knight is Rinaldo, the greatest of the Christian knights engaged in Tasso’s romanticised and largely fictional account of the First Crusade, who has stopped to rest near the ‘ford of the Orontes’. On hearing a woman singing, he goes to the river, where he catches sight of Armida swimming naked.

Armida, though, had an evil aim, in that she had been secretly following Rinaldo, intending to murder him with her dagger. As the ‘Saracen’ witch who is trying to destroy the crusaders’ campaign, she had singled out its greatest knight for this fate. Having revealed herself to him, she sings and lulls him into an enchanted sleep so that she can thrust her dagger home.

Just as she is about to do this, she falls in love with him instead, and that’s the instant, the twist or peripeteia (to use Aristotle’s term), shown here. A winged amorino, lacking the bow and arrows of a true Cupid, restrains her right arm bearing her weapon. Her facial expression and left hand reveal her new intent to enchant and abduct him in her chariot, so he can become infatuated with her, and forget the Crusade altogether.

This is a single moment in time, in which Poussin has ingeniously incorporated references to the past and future. Provided that you’re familiar with Tasso’s story, it’s a superb example of instantaneous narrative, as practised throughout the history of painting across all continents and cultures.

Jean-Léon Gérôme (1824–1904), Cleopatra before Caesar (1866), oil on canvas, 183 x 129.5 cm, Private collection. Wikimedia Commons.

Jean-Léon Gérôme’s Cleopatra before Caesar (1866) also depicts a single instant, but again has references to prior events, particularly the screwed up carpet, used by Cleopatra to gain entry. Her dreamy look towards Caesar also anticipates her affair with him. It therefore has instantaneous narrative.

Edward Burne-Jones (1833–1898), Cinderella (1863), watercolour and gouache on paper, 65.7 x 30.4 cm, Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, MA. Wikimedia Commons.

Sometimes paintings with instantaneous narrative can make quite small and subtle references to other events in the story, and confirm their narrative nature. In Edward Burne-Jones’s Cinderella (1863) the only such reference is the missing slipper on Cinderella’s right foot.

Édouard Detaille (1848–1912), Le Rêve (The Dream) (1888), oil on canvas, 300 x 400 cm, Musée d’Orsay, Paris. By Enmerkar, via Wikimedia Commons.

Although Édouard Detaille’s Le Rêve (The Dream) (1888) contains two images, these aren’t in fact linked by normal narrative, but the dream image shown in the clouds could be considered as a form of analepsis, or flashback, making it instantaneous narrative.

Multi-image

I’ll be brief with these, as I have covered more examples here and here.

Arthur Hughes (1832–1915), The Eve of St Agnes (1856), oil on canvas, 71 x 124.5 cm, The Tate Gallery, London (Bequeathed by Mrs Emily Toms in memory of her father, Joseph Kershaw 1931). Photographic Rights © Tate 2016, CC-BY-NC-ND 3.0 (Unported), http://www.tate.org.uk/art/artworks/hughes-the-eve-of-st-agnes-n04604

In 1856, Arthur Hughes told the story of The Eve of St Agnes in this triptych, read from left to right. At the left Porphyro is approaching the castle. In the centre he has woken Madeline, who hasn’t yet taken him into her bed. At the right the couple make their escape over drunken revellers.

Akseli Gallen-Kallela (1865–1931), Aino Myth, Triptych (1891), oil on canvas, overall 200 x 413 cm, middle panel 154 x 154 cm, outer panels 154 x 77 cm, Ateneum, Helsinki. Wikimedia Commons.

Akseli Gallen-Kallela’s triptych showing the Aino Myth (1891) contains three separate images telling one of the stories from the Kalevala myths. It is therefore multi-image narrative, within which each image is itself conventional instantaneous narrative.

Multi-frame

Multi-frame paintings are by no means uncommon, but most usually adopt rectangular or square form. Indeed many of the more spectacular frescoes are in effect multi-framed, where there are several images on a single continuous surface. This is similar to the more recent development of comics/BD/graphic novels.

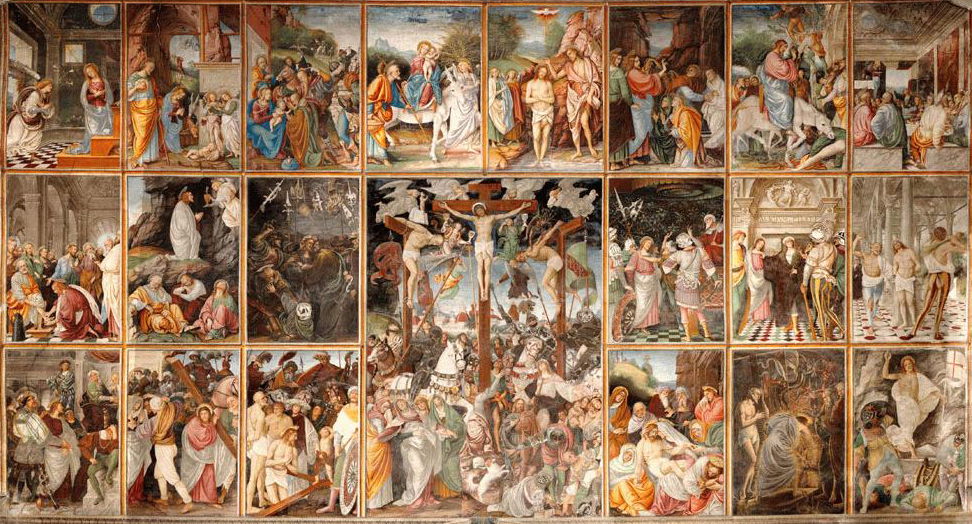

Gaudenzio Ferrari (1475–1546), Stories of The Life and Passion of Christ (1513), fresco, dimensions not known, Church of Santa Maria delle Grazie, Varallo Sesia (VC), Italy. Wikimedia Commons.

Gaudenzio Ferrari’s Stories of The Life and Passion of Christ (1513) arranges twenty frames covering the life of Christ around a central frame with four times the area of the others, showing the Crucifixion. The frames are naturally (for the European) read from left to right, along the rows from top to bottom, although the Crucifixion is part of the bottom row. This is a layout which is commonly used throughout graphic novels too, of course, and is a superb example of multi-frame narrative more than three centuries before Rodolphe Töpffer started experimenting with comic form.

Hans Sebald Beham (1500–1550), Scenes from the Life of David (1534), oil on panel, 128 x 131 cm, Musée du Louvre, Paris. Wikimedia Commons.

The four separate episodes forming Hans Sebald Beham’s Scenes from the Life of David (1534) are arranged in a square, so that each occupies a triangular frame, clearly separated from the others, and quite different from a normal linear layout. The snag with this is that the panel is really only suitable for viewing when laid flat on a table, otherwise only one of the frames is correctly orientated. Beham clearly liked the symmetry afforded by this layout, and enhanced it in his composition of the two frames shown here at the top and bottom.

Frans Francken the Younger (1581–1642) attr., The Crucifixion of Christ, with Scenes from the Life of Jesus (1600s), oil on oak panel, 91 x 70 cm, Private collection. Wikimedia Commons.

Frans Francken the Younger’s The Crucifixion of Christ, with Scenes from the Life of Jesus (1600s) puts the Crucifixion scene at the centre of a rectangle, around which are twelve scenes from the life painted in either normal or brown grisaille. Unfortunately those peripheral scenes are difficult to differentiate from one another, thus to identify, but they appear to be read in a clockwise direction from the upper right, rather than linearly.

Polymythic

John William Waterhouse (1849–1917), Echo and Narcissus (1903), oil on canvas, 109.2 x 189.2 cm, Walker Art Gallery, Liverpool, England. Wikimedia Commons.

Although linked, and often told together, the stories of Echo and of Narcissus can be separated, and it’s therefore feasible to classify John William Waterhouse’s Echo and Narcissus (1903) as being unusual in showing polymythic narrative.

Diego Velázquez (1599–1660), The Spinners (Las Hilanderas, The Fable of Arachne) (c 1657), oil on canvas, 220 x 289 cm, Prado Museum, Madrid. Wikimedia Commons.

A few paintings appear even more complex: Velázquez’s Las Hilanderas (The Spinners) may contain one narrative in the foreground, a second in the background, and a third in the painting of The Rape of Europa shown in the far background. This would make it polymythic narrative at the very least.