Emily Carr’s paintings, 1914-1930

The 1913 solo exhibition of two hundred of Emily Carr’s paintings of totems and villages of the First Nations in the Pacific North-West flopped. Despite trying to enlist the support of the minister of education in British Columbia, her art had been rejected, and was even refused by the new provincial museum. She returned to Victoria, opened a boarding house on Simcoe Street, and seldom painted. But she didn’t stop painting altogether, and by the late 1920s had started travelling to First Nations villages again to study and paint their culture.

Emily Carr (1871–1945), Logging Camp (c 1920), oil on board, 53 x 63 cm, Private collection. The Athenaeum.

She continued to paint in Fauvist style over this time, as seen in her Logging Camp (c 1920).

Emily Carr (1871–1945), Arbutus Tree (1922), oil on canvas, 46 x 36 cm, National Gallery of Canada / Musée des beaux-arts du Canada, Ottawa, ON. The Athenaeum.

This painting of an Arbutus Tree (1922) is a fascinating contrast with her previous watercolour of the same species from about 1909. This tree is painted much more loosely and in vibrant high chroma.

In 1924, Emily Carr met with Seattle artists, most importantly Mark Tobey, who helped rebuild her confidence in her art.

Emily Carr (1871–1945), Self-portrait (1924-25), oil on paperboard, 39.4 x 44.9 cm, Emily Carr Trust. Wikimedia Commons.

Her Self-portrait from 1924-25 shows her still suffering from rejection, though. Most unusually for a self-portrait, she faces away from the viewer, and is working on a painting that is unrecognisably vague and formless.

A visit by Eric Brown, director of the National Gallery of Canada, made 1927 the turning point in Carr’s art. She was invited to join the Group of Seven for a major exhibition in Ottawa, and twenty-six of her oil paintings, together with pottery and hooked rugs made when running the boarding house, were shown there. She became particularly close to Lawren Harris (1885-1970), who became her mentor.

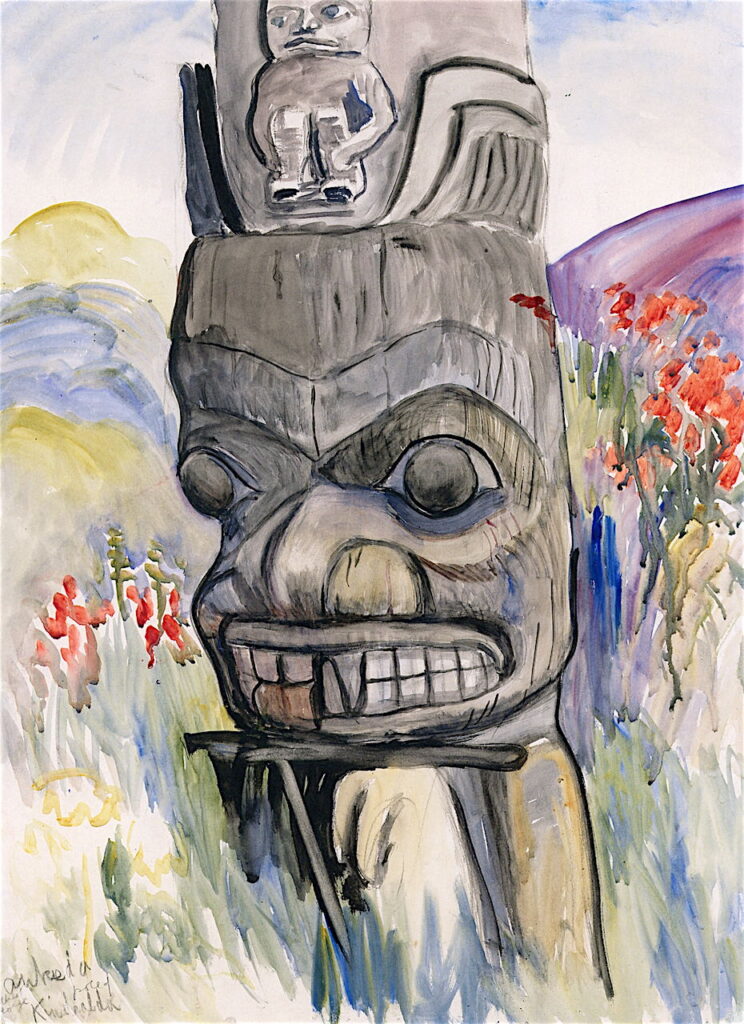

Emily Carr (1871–1945), Ankeda (1928), watercolour and graphite on paper, 76.3 x 56.4 cm, Vancouver Art Gallery, Vancouver, BC. The Athenaeum.

In the summer of 1928, Carr made her first major trip north since 1913, to the Nass and Skeena Rivers and Haida Gwaii. Among the more significant paintings which resulted is this superb watercolour of a totem presumably at Ankeda (1928).

Emily Carr (1871–1945), Kitwancool (1928), oil on canvas, 101.3 x 83.2 cm, Glenbow Museum, Calgary, AB. Wikimedia Commons.

Kitwancool (1928) shows a forest of poles at a village now known as Gitanyow, populated by the Gitxsan. This is near the Kitwanga River, a tributary of the Skeena, in north-west British Columbia. This village is now a National Historic Site.

Emily Carr (1871–1945), Queen Charlotte Islands Totem (1928), watercolour, 76.2 x 53.8 cm, Vancouver Art Gallery, Vancouver, BC. The Athenaeum.

Carr’s watercolour of a Queen Charlotte Islands Totem (1928) shows another site in what’s now known as Haida Gwaii, which she had visited extensively during her earlier campaigns prior to 1913.

Emily Carr (1871–1945), The Raven (1928-1929), oil on canvas, 61 x 45.7 cm, Vancouver Art Gallery, Vancouver, BC. The Athenaeum.

The Raven (1928-19) is a precursor of one of Carr’s best-known paintings, Big Raven (1931), and shares with it a motif based on a huge carved raven silhouetted against the sky, and the sculptural forms of trees. These were derived from an early watercolour painted at Cumshewa in 1912, showing this massive totem. It heralds her new emphasis on the modelling of forms, influenced by Lawren Harris in particular.

Emily Carr (1871–1945), Blunden Harbour (c 1930), oil on canvas, 129.8 x 93.6 cm, National Gallery of Canada / Musée des beaux-arts du Canada, Ottawa, ON. Wikimedia Commons.

Blunden Harbour (c 1930) shows Carr’s evolving style well. This village, inhabited by ‘Nak’waxda’xw (Nakoaktok) of the Kwakwaka’wakw peoples, was on the coast of the British Columbian mainland opposite Haida Gwaii, seen to the right, at the mouth of the Queen Charlotte Strait. As an isolated community, its population was forced to relocate to Port Hardy, about sixteen miles away, in 1964. Before the last of its inhabitants had even left in their boats, officials set fire to the village and burnt it to the ground, ensuring that no one would try to return.

The source of Carr’s motif remains uncertain; it has been claimed that she painted this from a photograph of the village taken in 1901 by the ethnographer Charles F Newcombe. However, the great majority of Carr’s paintings of the north-west appear to have been painted from life, rather than using old photographs taken by others.

Emily Carr (1871–1945), Path among Pines (c 1930), oil on paper, Vancouver Art Gallery, Vancouver, BC. Wikimedia Commons.

Path among Pines (c 1930) is another sign of the changes taking place in Carr’s art at this time. Its trees are solid forms, with swirling hues over their surfaces. The path swoops up into the distance in a carved curve. Totems would remain important in Carr’s art, but she was now also taking to the forest.

By 1930, her career had been transformed. She was a national if not international success, and travelled to New York, where she met Georgia O’Keeffe among others, and exhibited with the Group of Seven that year.

References

Wikipedia.

Lisa Baldissera (2015) Emily Carr, Life & Work, Art Canada Institute. ISBN 978 1 4871 0044 5. Available in PDF from Art Canada Institute.

Thom, Ian M (2013) Emily Carr Collected, Douglas & McIntyre. ISBN 978 1 77100 080 2.