A brief history of Mac CPUs

Macs have used four different architectures for their Central Processing Units over the last 40 years. From their launch by Steve Jobs on 24 January 1984, for the first decade they used Motorola 68K CPUs, then switched to PowerPCs designed by an alliance of Apple, IBM and Motorola, which were used for 12 years. After 14 years being built around Intel processors from 2006, Macs most recently changed a third time to use Apple’s own Arm-based chips.

Over those 40 years, continuous improvements in capabilities and performance of CPUs have transformed Mac OS and the apps it supports.

Motorola 68K

CPUs execute instructions in synchrony with a clock whose frequency determines the rate of instruction execution. The Motorola 68000 processor in the original Mac 128K ambled along at a clock speed of just 8 MHz. The last 68K models featuring 68040 CPUs had raised that to 33 MHz, and added specialist Memory Management Units (MMUs) and floating point units. The latter first appeared as 68881 and 68882 maths co-processors, but were later integrated into the 68040.

MMUs were particularly important for the implementation of virtual memory. When the Macintosh II was introduced in 1987, it was the first Mac that could be fitted with Motorola’s optional 68851 paged MMU, required for it to run Apple’s A/UX port of Unix with virtual memory support. Strangely, Apple’s own MMU fitted in the standard Mac II didn’t support virtual memory. Its 68020 CPU was also the first in Macs to use 32 bits rather than the 16 of the original 68000.

AIM PowerPC

When introduced in 1994, the first Power Macs came with PowerPC 601 or 601+ CPUs running at frequencies up to 110 MHz, nearly 14 times faster than the original Mac 128K. Just over a decade later, the last Power Mac G5 raised that to dual two-core CPUs at 2,500 MHz, more than 20 times the clock frequency, and the previous model had offered dual 2,700 MHz CPUs.

PowerPCs had their origins in IBM’s high-end POWER architecture based on a reduced instruction set (RISC) intended to be run at higher frequencies. Initially, these CPUs used a 32-bit design, but progressed to 64 bits. Not only do they have integrated floating point units that were extended for Apple, but later models include AltiVec vector processing for single-precision floating point and integer operations.

High CPU frequencies bring higher power consumption and heat output. A dual-core G5 with a PowerPC 970MP CPU used a maximum of 100 W at 2,000 MHz, and some of the last G5 Macs used liquid cooling to cope with the heat generated at higher frequencies. Those didn’t prove long-lived, with coolant leaks a common and fatal failing.

Intel x86

In early 2006 Apple started releasing its new range of Macs using Intel CPUs. With the exception of a base model of Mac mini, those came with 2-core Core Duo processors running at up to 2 GHz, and were soon followed by the first Mac Pros featuring two 64-bit 2-core Xeon 5100 CPUs (Woodcrest) at up to 3 GHz. By the following year, the first 8-core Mac Pro was available.

Earlier increases in CPU frequency gradually petered out. The last Intel Mac Pro was available with cores running at 2.5-3.5 GHz, boosted to a maximum of up to 4.4 GHz. Instead, high-end models offered as many as 28 cores and drew power up to 900 W. More typical of late desktop Macs were Intel Core i9 CPUs with 6-8 cores at similar frequencies. Adding more processor cores has been an effective way to run more code at the same time. Tasks are divided into threads that can run relatively independently of one another. Those threads can then be distributed across several CPU cores.

Rising power consumption and heat output were becoming even more of a problem in MacBook Pro models.

Apple Arm

Well before Apple had joined IBM and Motorola in the AIM alliance, it had co-founded the company based in Cambridge, England, that was to become ARM (for Acorn RISC Machines). Its RISC processor was used in Apple’s Newton MessagePad of 1993, and in 2010 Apple released its first iPhone and iPad designed around a single-core 32-bit Arm CPU running at a cool and economical 1 GHz.

From before macOS Mojave in 2018, Apple was preparing for its next migration, to its own integrated Systems on a Chip (SoC), starting with the M1 in 2020. The first iPhone to incorporate two CPU core types was the iPhone 7 of 2016, in its A10 Fusion SoC. Rather than simply adding more cores, Apple had adopted the Arm big.LITTLE architecture, in which background threads are run on slower, more efficient CPU cores, and higher priority user processes run on faster, more performant cores.

The first two families of M1 and M2 chips have cores grouped in clusters of no more than 4, but Apple increased cluster size to 6 in the M3 and M4. While the M1 family consists of two designs, one for the base variant, and the second for both Pro and Max, and doubled in the Ultra, M3 and M4 families have distinct designs for their Pro and Max variants. For the M4, this offers a full range from 8 to 16 cores in total, with an anticipated Ultra extending to 32. In addition to CPU cores with built-in vector processing (NEON), these chips incorporate specialist co-processors such as a neural engine and a proprietary matrix co-processor, AMX.

Performance (‘big’) cores have increased in maximum frequency, from 3.2 GHz in the M1 to 4.5 GHz in the M4 four years later.

Trends

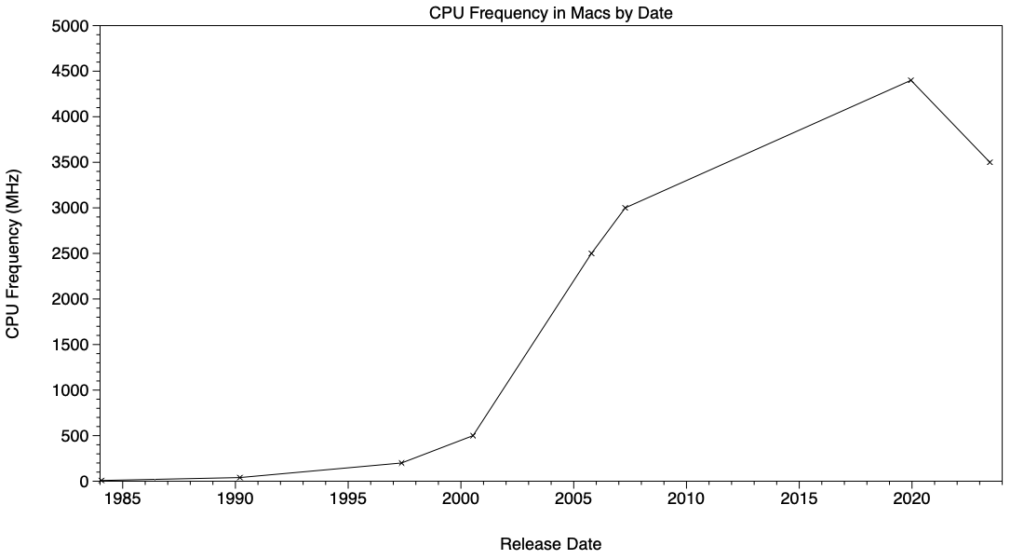

The period 1984-2007 was dominated by increasing CPU frequency, as demonstrated in the two charts below.

This chart uses a conventional linear Y axis to demonstrate that frequency rose rapidly during the decade from 1997. As the form of this curve is S-shaped, the chart below shows the same data with a logarithmic Y axis.

Since about 2007, Macs haven’t seen substantial frequency increases. Many factors limit the maximum frequency that a processor can run at, including its physical dimensions, but among the most significant in practical terms are its power requirements and heat output, hence its need for cooling. Thus, the period 2005-2017 became dominated by increasing core count.

This chart shows how the number of processors and cores inside Macs didn’t start rising until around 2005, just as frequencies were topping out. Thus, many of the CPU performance improvements from 2007 onwards have been the result of providing more cores. But there’s a practical limit as to how many of those cores will get used, which is where processing more data becomes important, as it has from 1998 onwards.

It’s remarkable how much of Mac OS has survived if not flourished over those 40 years that our Macs have gone from a pedestrian Motorola 68000 processor to the 12 performance cores capable of 4.5 GHz in an M4 Max chip.