Reading visual art: 177 Peace, modern

In yesterday’s article, I showed examples of paintings using classical deities and resolved conflicts in ancient history to depict the concept of peace. Today I move on to more recent and modern history.

Benjamin West (1738–1820), The Treaty of Penn with the Indians (1771-72), oil on canvas, 190 x 274 cm, Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts, Philadelphia, PA. Wikimedia Commons.

Benjamin West was commissioned by William Penn’s son Thomas to paint The Treaty of Penn with the Indians or William Penn’s Treaty with the Indians (1771-72), the one ‘modern history’ painting he showed alongside four more traditional narrative works at the Royal Academy in 1772.

This shows the Quaker founder of the state of Pennsylvania purchasing land for his colony from the Lenape people, with a treaty of peace between the colonists and the ‘Indians’, an event that took place ninety years earlier in 1682. This proved as popular and successful as West’s famous painting of The Death of General Wolfe, being reproduced in prints and on all manner of other surfaces, even bedspreads! Like that earlier work, it was also savaged for its historical inaccuracies, to say nothing of its misrepresentation of the reality of westward expansion in North America.

In 1867, France was in the process of sliding inexorably towards its war with Prussia, and the Second Empire of Napoleon III was about to self-destruct.

Pierre Puvis de Chavannes (1824–1898), Peace (1867), oil on canvas, 109 x 148.7 cm, Philadelphia Museum of Art, Philadelphia, PA. Wikimedia Commons.

Pierre Puvis de Chavannes painted a pair of allegories, Peace (above), and War (below), using colours stronger than usual to enable reading of their greater detail. Both are set in classical times in an idyllic landscape. Peace is a group dolce far niente that might later have passed for Aestheticism: men, women and children engaged in nothing more strenuous than milking a goat.

In War, three horsemen are blowing a fanfare on their war trumpets, haystacks in the surrounding fields are alight and pouring black smoke into the sky, and the people are suffering, even though signs of destruction are slight and none is wounded.

Pierre Puvis de Chavannes (1824–1898), War (1867), oil on canvas, 109.6 x 149.3 cm, Philadelphia Museum of Art, Philadelphia, PA. Wikimedia Commons.

By the start of 1871, Prussia had inflicted a crushing defeat on France, whose Second Empire was forced to agree an armistice.

Édouard Detaille (1848–1912), The Armistice of 28th January 1871 (1873), media and dimensions not known, Deutsches Historisches Museum, Berlin, Germany. Wikimedia Commons.

Édouard Detaille’s depiction of The Armistice of 28th January 1871 (1873) shows the moment that the symbolic white flag was raised, over a bleak plain.

Vasily Vasilyevich Vereshchagin (1842–1904), The Apotheosis of War (1871), oil on canvas, 127 x 197 cm, Tretyakov Gallery Государственная Третьяковская галерея, Moscow, Russia. Wikimedia Commons.

By a strange coincidence, that same year the Russian war artist Vasily Vasilyevich Vereshchagin painted his powerful Apotheosis of War (1871), showing ravens or crows perching on a huge pile of human skulls in a barren landscape outside the ruins of a town. This was his reaction to the series of battles fought by the Russian Empire against those living in lands that it wanted to acquire.

My final paintings are products of what was then known as the Great War, but proved to be only the first of the two World Wars of the twentieth century.

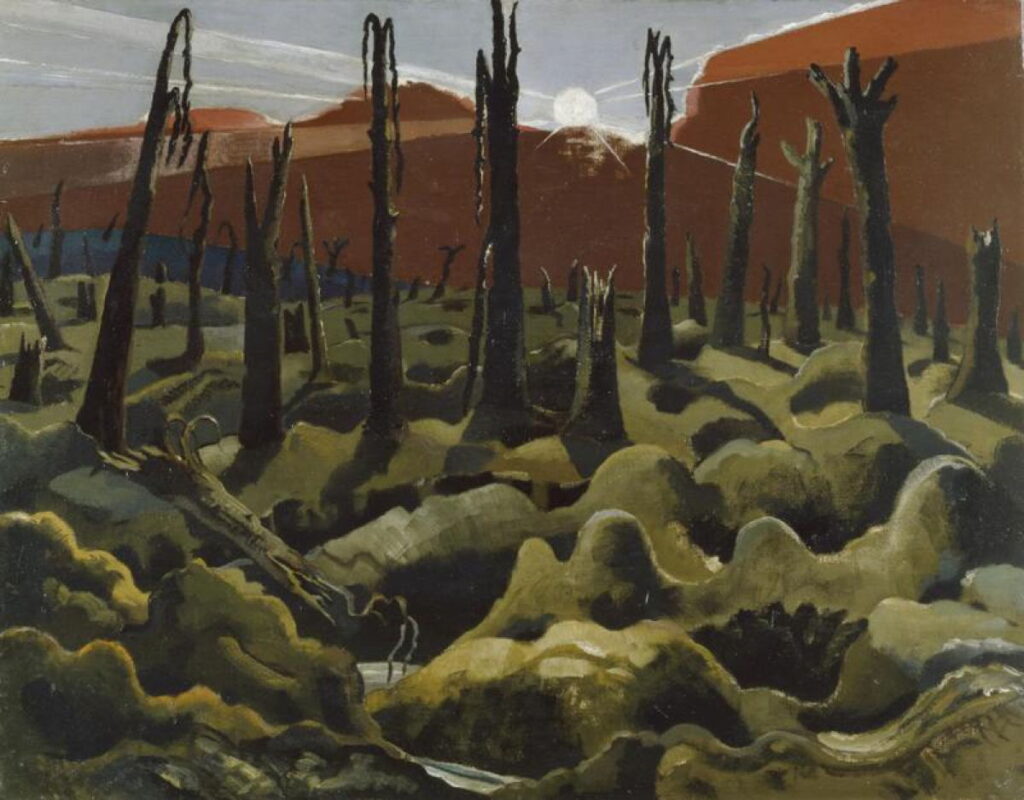

Paul Nash (1892–1946), We are Making a New World (1918), oil on canvas, 71.1 x 91.4 cm, The Imperial War Museum, London. By courtesy of The Imperial War Museums © IWM (Art.IWM ART 1146).

Paul Nash’s pen and ink drawing of Sunrise: Inverness Copse, showing the aftermath of heavy fighting during the Battle of Langemarck, became his finished oil painting of We are Making a New World (1918). Although richer in colour, the slime green furrowed mud dominates the lower half of the canvas. Its intensely ironic title and use of the early morning sun makes the artist’s response to the war very clear, and it has remained one of the strongest images of that war.

Paul Nash (1892–1946), The Menin Road (1919), oil on canvas, 182.8 x 317.5 cm, The Imperial War Museum, London. By courtesy of The Imperial War Museums © IWM (Art.IWM ART 2242).

Nash’s Menin Road (1919) was commissioned by the British War Memorials Committee in April 1918 for its Hall of Remembrance. It shows a section of the Ypres Salient known as Tower Hamlets, after what is now a part of eastern London. This area was destroyed during the Battle of the Menin Road Ridge.

Sir William Nicholson (1872–1949), The Cenotaph the Morning of the Peace Procession (1919), further details not known. Wikimedia Commons.

William Nicholson’s The Cenotaph the Morning of the Peace Procession is an interesting historical record of 1919, as well as a detailed oil sketch. The cenotaph shown here isn’t the current memorial in central London, but a temporary structure erected for a ‘peace celebration’, also known as a ‘victory parade’, that took place in London on 19 July 1919, following the signing of the Treaty of Versailles to formally end that war.

This was designed very quickly by Sir Edwin Lutyens, approved on 7 July, and hastily constructed in wood and plaster. It was unofficially unveiled on the day before the celebration, and soon attracted the laying of wreaths by the public. Following great public demand, a permanent version was constructed to a slightly modified design the following year, and that remains the focus for all similar events in London. Just twenty years later the world was dragged into yet another war.