A brief history of Mac memory and its management

While memory and its management have been important in the history of all computers, they were nearly the downfall of the first Macintosh, the original 128K named because it came with just 128 KB of RAM. That proved barely sufficient for demonstration purposes, and by the autumn/fall of 1984 had been replaced by the ‘Fat Mac’ with 512 KB costing an extra $700. Apple proved quick to demonstrate that memory for its new Mac products was never going to come cheap, when it came at all.

It took another couple of years for the Mac Plus, the first that came with memory slots to increase its standard memory from 1 to 4 MB, and from then pretty well every Mac had slots to accommodate expansion. By the IIx of 1988, those slots could accommodate a maximum of 128 MB, a thousand times that in the 128K Mac.

In early 1989, Connectix introduced Virtual, the first implementation of virtual memory for System 6. Two years later, in May 1991, Apple provided its own implementation in System 7, but its use remained optional even in System 8.6 eight years later. Some apps required it, while others couldn’t run when it was enabled. Most users stuck with only enabling it when their software needed it, and made do with the limitations of physical memory of 384 MB or less.

The maximum my Blue & White Power Mac G3/350 could accommodate was just 1 GB. As apps were far more conservative in their memory requirements, this worked better than you might expect.

My Power Mac G3 worked well with Mac OS taking its lion’s share of just over 50 MB, my mail client with less than 7 MB, and the whole of Microsoft Word in under 20 MB. But apps could and did run out of memory, when they would simply quit with an error alert, something we grew familiar with.

Memory leaks still plagued Mac OS 8, and many users had to resort to utilities like R Fronabarger’s freeware Memory Mapper to track free memory and try to understand what was going on.

One memory problem never fixed in Mac OS 8.x occurred in many apps including Web browsers, Microsoft Office 98, and others. Using these led to a progressive reduction in the amount of contiguous free memory, until eventually the whole Mac crashed. This appeared worst in Macs with most physical memory, and although some patches were produced by third-parties, none was a complete solution. The only workaround was to keep an eye on memory, and restart the Mac before a crash occurred.

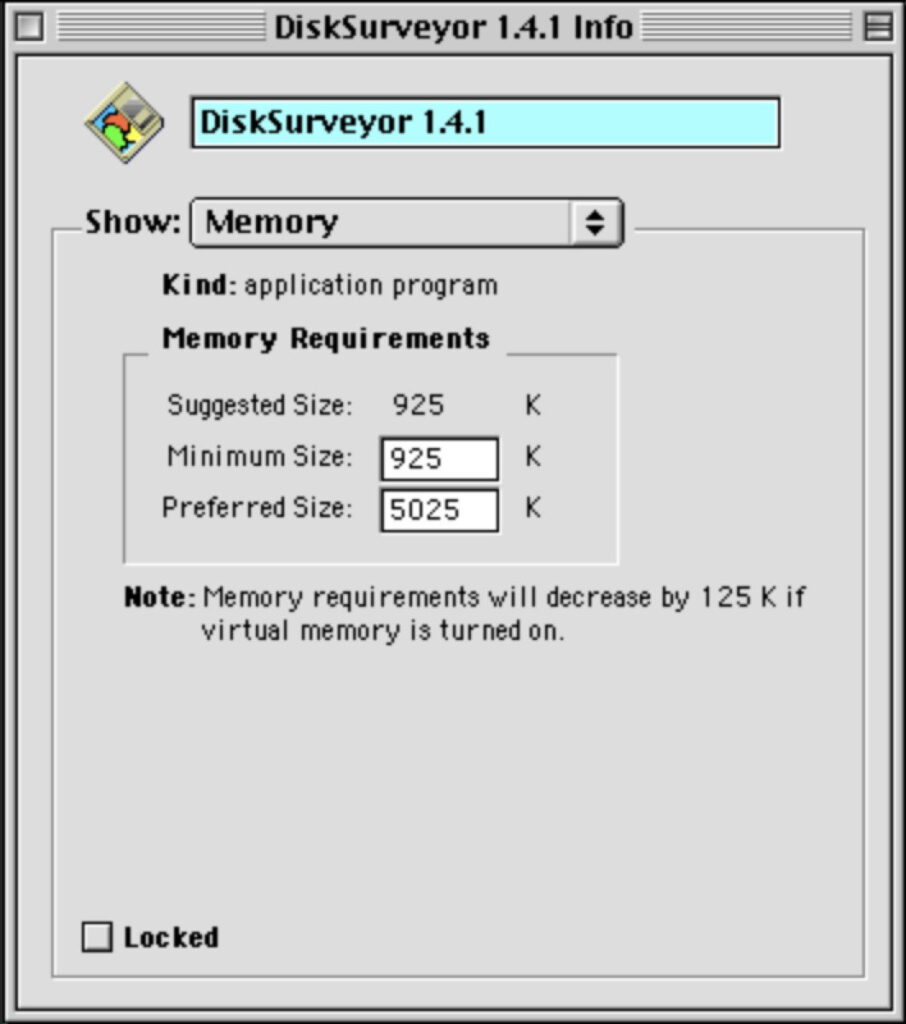

In those days, you had to set the amount of memory to be allocated to each app in the Finder’s Get Info dialog. Getting this right was usually a matter of trial and error.

Although Classic Mac OS had such a struggle managing memory, the first Mac to support proper virtual memory had been the Macintosh II in 1987. That required it to be fitted with Motorola’s 68851 paged MMU chip, an option needed to run Apple’s A/UX port of Unix. That chip was no longer needed in Motorola 68030 and 68040 processors, as its functions were then integrated into the CPU.

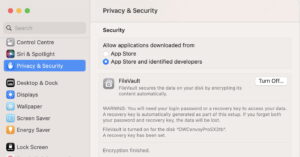

Mac OS X was completely different, with virtual memory a permanent feature, and greatly improved management by the kernel. But memory leaks continued, and we learned the pain brought by those in Mach zone memory, memory blocks allocated for use by the kernel and its extensions. That happened as recently as macOS Catalina 10.15.6, when they caused kernel panics. Memory leaks, fortunately not affecting Mach zones this time, also troubled macOS 12.0.1.

Physical memory continued to grow in size, by the last of the Power Macs reaching 8 or even 16 GB in high-end models. Intel models offered even more, and by early 2009 8-core Mac Pro models could accommodate up to 128 GB, although Apple officially claimed a mere 32 GB. The original MacBook Air of 2008 was the first to ship with fixed memory, 2 GB that couldn’t be upgraded, and that became more general among models released from 2015 onwards.

With the advent of Apple silicon Macs came the greatest change in memory management and use since the release of Mac OS X twenty years earlier: instead of having separate physical memory for devices like GPUs, M-series chips use Unified Memory, one pool for use by CPU cores, GPU, and much else apart from the Secure Enclave. Unfortunately, that has also brought RAM to be integrated into the M-series chip carrier, even in those fitted to the Mac Pro.

Macs have thus returned to one of the problems of the original 128K of forty years ago, and once again their memory can’t be upgraded.