Inglorious mud: 2 To the War to End Wars

In the first of these two articles showing the more faithful accounts of winter with its inglorious mud, I had reached the late nineteenth century and sunk into the mud of a Polish country market. Today’s paintings take that on into the twentieth century and the Great War, claimed at the time to be the War to End Wars.

Fritz von Uhde (1848–1911), A Difficult Journey (Transition to Bethlehem) (1890), oil on canvas, 117 × 127 cm, Neue Pinakothek, Munich, Germany. Wikimedia Commons.

Mud plays a significant role in this unusual modernised religious story by Fritz von Uhde, A Difficult Journey from 1890. This imagines Joseph and the pregnant Mary walking on a rough muddy track to Bethlehem, in a wintry European village. Joseph has a carpenter’s saw on his back as the tired couple move on through the dank mist.

Although the Franco-Prussian War started in the summer of 1870, its later stages, including much of the fighting around Paris and its siege took place in the late autumn and winter, when mud was at its height, or depth.

Anton von Werner (1843–1915), In the Troops’ Quarters Outside Paris (1894), oil on canvas, 120 x 158 cm, Alte Nationalgalerie, Berlin, Germany. Wikimedia Commons.

Anton von Werner’s In the Troops’ Quarters Outside Paris, from 1894, shows muddy soldiers in the luxurious Château de Brunoy, which had been abandoned to or requisitioned by occupying forces. Every boot seen is caked in mud, which covers the trouser legs of the orderly who is tending to the fire.

Artists in the Nordic countries were also starting to depict mud more faithfully in their paintings.

Laurits Andersen Ring (1854–1933), Father Coming Home (1896), oil on canvas, 74.5 x 59.5 cm, Statsministeriet, Copenhagen, Denmark. Wikimedia Commons.

Laurits Andersen Ring’s Father Coming Home from 1896 shows a mother and two children awaiting the return of their husband and father. He is still quite distant along the muddy track in this poor rural community in Denmark.

Nikolai Astrup (1880–1928), Farmstead in Jølster (1902), oil on canvas, 73 x 100 cm, Bergen Kunstmuseum, KODE, Bergen, Norway. The Athenaeum.

Further north in the valleys of Norway, Nikolai Astrup painted Farmstead in Jølster in 1902. Two women, sheltering from the rain under black umbrellas, are walking up a muddy path threading its way through the wooden farm buildings, guiding a young girl with them. Astrup delights in the colourful patches making up the turf roofs, and the contrasting puddles on the grass. His unusual aerial view might prevent us from seeing the mud covering the hems of their coats and dresses, but we know it’s there.

Laurits Andersen Ring (1854–1933), Short Stay (1909), media not known, 82 x 97 cm, Niedersächsisches Landesmuseum Hannover, Hanover, Germany. Wikimedia Commons.

A few years later, Ring painted Short Stay (1909), showing an elderly man and woman standing in the mud in silence and facing in opposite directions. He’s towing a small sledge bearing a sack; she’s carrying a basket containing a large fresh fish wrapped in paper.

Hans Andersen Brendekilde (1857–1942), Village Scene in the Early Spring (1911), oil on canvas, 62 x 84 cm, location not known. Wikimedia Commons.

Ring’s friend Hans Andersen Brendekilde painted this Village Scene in the Early Spring in 1911. The rutted mud track is slowly drying from its winter role as the main drain. A man is out cleaning the tiny windows of his cottage, and two women have stopped to talk in the distance. Smoke curls idly up from a chimney, and leafless pollards stand and wait for the season to progress.

Three years later, this muddy peace was shattered when Europe went to war, digging trenches across great swathes of the muddy fields of northern France and Belgium.

C R W Nevinson (1889-1946), Paths of Glory (1917), oil on canvas, 45.7 x 60.9 cm, The Imperial War Museum, London. By courtesy of The Imperial War Museums © IWM (Art.IWM ART 518).

An official war artist, CRW Nevinson’s Paths of Glory was exhibited with a quotation from Thomas Gray’s Elegy Written In A Country Church-Yard (1750):

The boast of heraldry, the pomp of power,

And all that beauty, all that wealth e’er gave,

Awaits alike the inevitable hour.

The paths of glory lead but to the grave.

Like Marshall Ney, the bodies in Nevinson’s famous depiction of the aftermath of war lie face down in the mud. Here it isn’t dust to dust, or ashes to ashes, but mud to mud. Rifles, helmets and the men’s bodies are being engulfed in all-enveloping mud.

François Flameng (1856–1923), Attack (1918), further details not known. Wikimedia Commons.

Other artists who went to the front recorded different aspects of its mud. François Flameng’s view of an Attack (1918) being made on duckboards over flooded marshland, brings home a clear picture of what actually happened over and in that deadly mud. His war paintings, many of which weren’t published until the end of the war, were criticised for being too real.

François Flameng (1856–1923), The Cliff of Craonne (1918), further details not known. Wikimedia Commons.

This scene of devastation at The Cliff of Craonne (1918) shows part of the battlefield of the Aisne in 1917 that gave rise to one of the famous anti-military songs of the Great War, La Chanson de Craonne. It’s a landscape where only the mud has escaped destruction.

Paul Nash (1892–1946), Wire (1918), watercolour on paper, 72.8 x 85.8 cm, The Imperial War Museum, London. By courtesy of The Imperial War Museums © IWM (Art.IWM ART 2705).

Typical of Paul Nash’s paintings of the Western Front is his watercolour Wire (1918). It shows a characteristically deserted and devastated landscape, the mud pockmarked with shell-holes and festooned with wire fencing and barbed wire. Its only landmarks are the shattered stumps of what was once pleasant countryside.

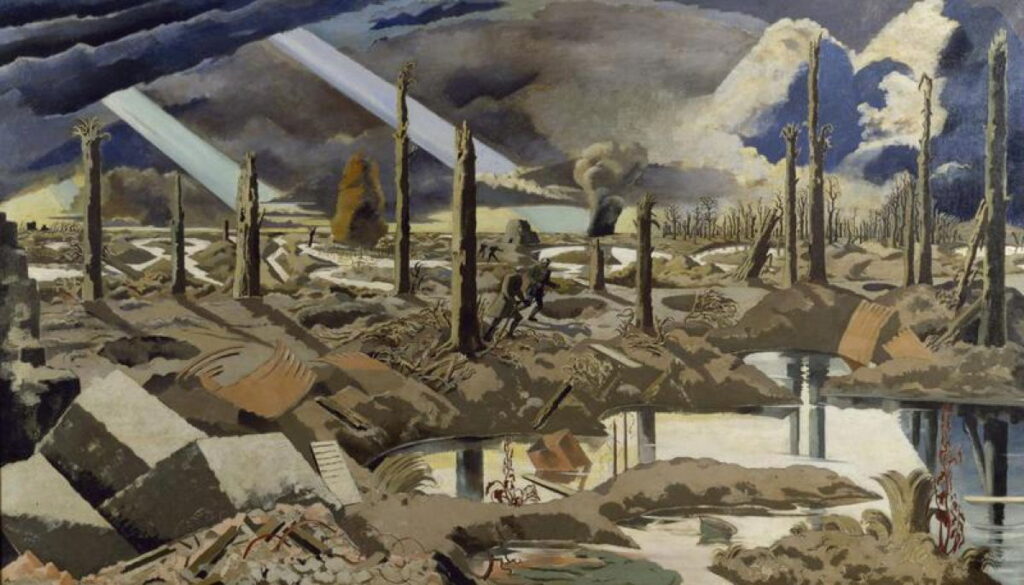

Paul Nash (1892–1946), The Menin Road (1919), oil on canvas, 182.8 x 317.5 cm, The Imperial War Museum, London. By courtesy of The Imperial War Museums © IWM (Art.IWM ART 2242).

Nash’s The Menin Road (1919) was commissioned by the British War Memorials Committee in April 1918 for its Hall of Remembrance, for which John Singer Sargent’s Gassed was also intended. It shows a section of the Ypres Salient known as Tower Hamlets, after what’s now a part of eastern London. This area was reduced to barren mud during the Battle of the Menin Road Ridge.

There I reach the end of this curiously brief history of mud in European painting. Perhaps it was just too commonplace to depict faithfully. But why might this mud be inglorious? There’s a wonderful Hippopotamus Song by the comedy duo Flanders and Swann with the refrain:

Mud, mud, glorious mud,

Nothing quite like it for cooling the blood.

So follow me, follow

Down to the hollow

And there let us wallow in glorious mud.