From the Commedia dell’Arte to Punch and Judy 2

Soon after the Commedia dell’Arte had spread across Europe, travelling performers started entertaining the public with a different but related show, that of Punch and Judy. Mr Punch, the lead male, is based on Pulcinella, who is now a trickster figure who batters his wife Judy. The first recorded show in Britain was on 9 May 1662, using marionette puppets. For the last two hundred years or so, a stylised version performed using glove or other puppets has been popular with children visiting British resorts. In 1827, George Cruikshank made a series of sketches of a performance that were turned into the first illustrated and printed script.

Punch and Judy not only developed its own stereotype characters, but evolved its own plots. At first these shows appeared in street circuses around the towns and cities of Europe, then gravitated towards seaside resorts as they became popular in the summer. Characters from the Commedia also appeared as clowns in more established travelling circuses across Europe and North America.

Philip Hermogenes Calderon (1833–1898), French Peasants Finding their Stolen Child (1859), oil on canvas, 42.5 × 33 cm, Private collection. Wikimedia Commons.

Philip Hermogenes Calderon’s French Peasants Finding their Stolen Child (1859) draws on the troubled lives of those itinerant players. Various characters from a popular street theatre play are seen at the side of their stage. A couple are embracing a young girl, with the girl’s apparent mother kissing her somewhat reluctant daughter on the cheek.

In the background are the audience, and other stalls of a travelling fair. Entertainers in such fairs were vulnerable to crimes such as child abduction, or it may be that the couple and their daughter aren’t part of the fair, but locals who had their daughter abducted by its travelling performers.

Honoré Daumier (1808–1879), The Parade, or Street Circus (c 1860), watercolour on paper, 26.6 × 36.7 cm, Musée du Louvre, Paris. Wikimedia Commons.

Honoré Daumier’s The Parade, or Street Circus from about 1860 shows a group of mountebanks, theatrical performers, musicians, and clowns who drew large crowds. The crocodile is one of several novel characters from these Punch and Judy shows.

Émile Friant (1863–1932), The Entrance of the Clowns (1881), media and dimensions not known, Private collection. The Athenaeum.

One of Émile Friant’s earliest works is this 1881 painting of The Entrance of the Clowns, showing the interior of the Big Top at the moment that the clowns, acrobats, and other entertainers parade. At the front is Pierrot, with Harlequin sprawling on the ground.

Paul Cézanne (1839–1906), Mardi Gras (Pierrot and Harlequin) (1888), oil on canvas, 102 x 81 cm, Pushkin Museum of Fine Arts Музей изобразительных искусств им. А.С. Пушкина, Moscow, Russia. Wikimedia Commons.

Among Paul Cézanne’s figurative paintings is this of Mardi Gras (Pierrot and Harlequin) from 1888.

Fernand Pelez (1848-1913), Grimaces et misères: les Saltimbanques (Grimaces and Miseries: the Acrobats) (smaller version) (1888), oil on canvas, 114.6 x 292.7 cm, Private collection. Wikimedia Commons.

The smaller of Fernand Pelez’ two paintings of Grimaces and Miseries: the Acrobats follows the pattern of a traditional ‘ages of man’ image, where its figures increase in stature from the start at the left edge, to the centre, then diminish again with advancing years, to the right. Standing in the middle are Pierrot and Harlequin.

Les Saltimbanques (Acrobats) had been a successful show in the theatre fifty years earlier, and had lived on in entertainments staged in fairs around France. Rosenblum summarises this painting as presenting “a glum view of the contrast between the goals of rousing entertainment in a popular Parisian circus troupe and the actual melancholy and isolation of the performers.” That sounds about right for Pierrot, at least.

Fernand Pelez (1848-1913), La Vachalcade (The Cow-valcade) (1896), media and dimensions not known, Musée du Petit Palais, Paris. Wikimedia Commons.

Pelez’ later La Vachalcade (The Cow-valcade) (1896) is a reversal of a portrait of an affluent family by way of parody. Thirteen young revellers are taking part in a carnival procession, perhaps one of the Vachalcades which took place in Montmartre at the time. Some wear masks, others have the close-shorn hair characteristic of the poor, a measure against endemic parasites.

At the centre is a boy wearing an adult’s jacket and a huge hat. Behind him is a Pierrot character, and in the background a banner bearing the word Misère, misery. Dangling on that is a dead rat, a reference to a well-known café on the Place Pigalle. The ‘vache’ (cow) in the title refers to the French phrase manger de la vache enragée, meaning to live in poverty.

Pierre-Auguste Renoir (1841–1919), The White Pierrot (1901-02), oil on canvas, 81.2 x 62.2 cm, Detroit Institute of Arts, Detroit, MI. Wikimedia Commons.

Pierre-Auguste Renoir painted this full-figure portrait of his son Jean as The White Pierrot during 1901-02.

Walter Richard Sickert (1860–1942), Pierrot and Woman Embracing (c 1901), gouache and chalk on paper, 41 x 31.1 cm, The Tate Gallery (Bequeathed by Lady Henry Cavendish-Bentinck 1940), London. © The Tate Gallery and Photographic Rights © Tate (2016), CC-BY-NC-ND 3.0 (Unported), https://www.tate.org.uk/art/artworks/sickert-pierrot-and-woman-embracing-n05095

Like Watteau earlier, the British painter Walter Sickert became interested in traditional pantomime, another derivative of the Commedia and Punch and Judy, seen in this gouache of Pierrot and Woman Embracing from about 1901. This is a preliminary sketch for a painting now in a private collection, Venetian Stage Scene.

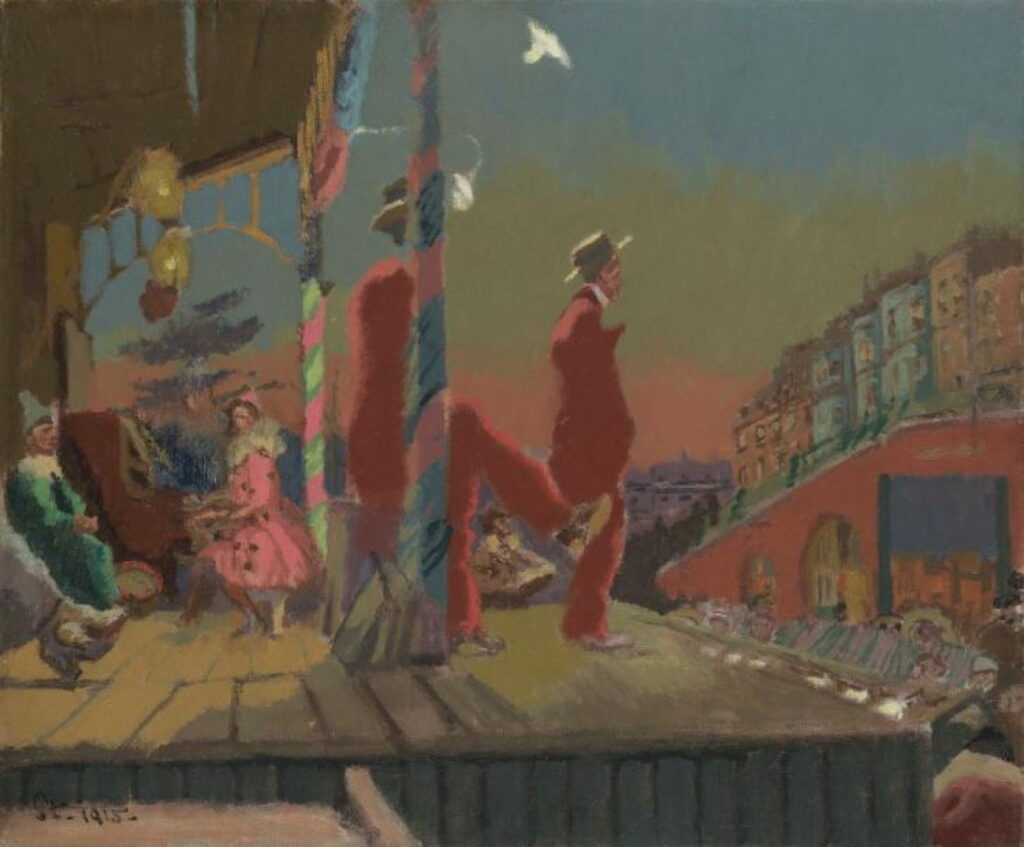

Walter Richard Sickert (1860–1942), Brighton Pierrots (1915), oil on canvas, 63.6 x 76.8 cm, The Tate Gallery (Purchased with assistance from the Art Fund and the Friends of the Tate Gallery 1996), London. © The Tate Gallery and Photographic Rights © Tate (2016), CC-BY-NC-ND 3.0 (Unported), https://www.tate.org.uk/art/artworks/sickert-brighton-pierrots-t07041

Sickert spent much of the summer of 1915 visiting Brighton, where he made studies for Brighton Pierrots. This is a commissioned copy of his original, which remains in a private collection, and like that was painted following his return to his London studio. It shows a small group of entertainers who performed daily on a temporary stage set up on the beach.

William S Horton (1865–1936), Punch on the Beach at Broadstairs, England (1920), oil on canvas, 64.5 × 78.1 cm, Hunter Museum of American Art, Chattanooga, TN. Wikimedia Commons.

Although William S Horton was born in Grand Rapids, Michigan, and trained in Chicago, Paris, and New York, he painted almost entirely in Europe. In about 1917, he arrived in Britain, and in 1920 painted this Punch and Judy show taking place on the beach at Broadstairs, Kent, a traditional family seaside resort at the extreme eastern tip of the south-east coast of England.

Edmond Aman-Jean (1858–1936), Festival of Venice (1923), oil on canvas, 214 x 430 cm, Ohara Museum of Art 大原美術館, Kurashiki, Japan. Wikimedia Commons.

Edmond Aman-Jean’s Festival of Venice from 1923 is set at an open-air performance involving a Harlequin character with a moustache, who is offering a woman a pink flower, presumably in an effort to woo her. At the right is a chorus of three women, and another sits asleep in a chair at the far right. A young woman seated at the front of the wooden stage is playing a hurdy gurdy, and a girl to the left of her is making a floral decoration.

The descendants of the commedia dell’arte live on, five centuries after the first Pierrots and Harlequins brought laughter to audiences.