Rescued from the sea-monster: Paintings of Andromeda

This weekend, in my occasional series looking at women in major narrative paintings, I cover two almost identical stories of women who are rescued from the jaws of a sea-monster: Andromeda, who was saved by Perseus in classical myth, and Angelica, who was rescued by Ruggiero in Ariosto’s epic Orlando Furioso.

Andromeda’s story forms a part of a far longer myth about Perseus, who at the opening of this has killed Medusa, and had an unfortunate clash with Atlas. At this time, Ethiopia was ruled by King Cepheus and Queen Cassiopeia. She had boasted of the beauty of her daughter Andromeda, and so incurred the wrath of Poseidon, including floods and a voracious sea monster named Cetus. The local oracle told the king and queen that the only way to save their people from Cetus was to sacrifice their daughter to the monster. Accordingly, and with great grief, they were forced to comply. Andromeda was therefore fastened to a rock at the edge of the sea to await Cetus.

With dawn about to break, Perseus gets himself together and flies away on his winged sandals, over Ethiopia, where he sees the beautiful Andromeda shackled to a rock. He immediately falls in love with her, and descends to chat her up.

Andromeda tells him a bit about herself, and is just about to explain the full story of how she came to be chained to the rock, when a huge monster rises up from the sea and heads towards the woman, intent on devouring her. With her parents stood helplessly by, Perseus offers to save her, in return for her hand in marriage; as they have no option, her parents consent, as the monster closes in on them.

Perseus takes to the air again and sinks the curved blade of his sword into the monster’s shoulder. The monster rears up, dives down, then reappears, for Perseus to wound it further. His winged sandals are now soaked with spray and blood, and struggling to keep him airborne. He therefore lands on a small rock, from where he finishes the monster off.

Andromeda is released, and Perseus makes offerings to the gods before preparing for his wedding with his newly-won bride.

Gustave Moreau (1826–1898), Perseus and Andromeda (1870), oil on panel, 20 x 25.4 cm, Bristol City Museum and Art Gallery, Bristol, England. Wikimedia Commons.

Gustave Moreau’s Perseus and Andromeda (1870) puts the shackled Andromeda, almost naked, in the foreground, with Cetus looking surprised at Perseus’ imminent arrival from the sky. The hero isn’t astride Pegasus, but wears his winged sandals, and flourishes his polished shield still bearing an image of Medusa’s head.

Frederic, Lord Leighton (1830–1896), Perseus and Andromeda (1891), oil on canvas, 235 × 129.2 cm, Walker Art Gallery, Liverpool, England. Wikimedia Commons.

Lord Leighton’s vision of Cetus in his Perseus and Andromeda from 1891 is one of the few fire-breathing monsters that fits the modern concept of a dragon. Its body is carefully arched over Andromeda as if protecting its prey from another predator, as Perseus arrives astride Pegasus.

Unknown, Perseus Freeing Andromeda (c 50-75 CE), height 122 cm, Casa dei Dioscuri (VI, 9, 6), Pompeii, moved to Museo Archeologico Nazionale di Napoli, Naples. By WolfgangRieger, via Wikimedia Commons.

This Roman wall painting from the ruins of Pompeii, dated to about 50-75 CE, adopts the approach typical of many later artists, showing a close-up of the couple. Andromeda is still chained to the rock by her left wrist, and is partially clad, nakedness being reserved for the hero and demi-god Perseus. He has Medusa’s head tucked behind him, the face shown for ease of recognition, wears his winged sandals, and carries a straight sword in his left hand. There’s no sign of any sea monster, though.

Titian (Tiziano Vecelli) (1490–1576), Perseus and Andromeda (1553-9), oil on canvas, 179 × 197 cm, The Wallace Collection, London. Wikimedia Commons.

Titian’s Perseus and Andromeda (1553-59) improves on that by showing the height of the action, remaining largely faithful to Ovid’s details. All three actors are present, with Andromeda still shackled and Perseus attacking Cetus from the air using a sword with a curved blade.

Paolo Veronese (1528–1588), Perseus Rescuing Andromeda (1576-78), oil on canvas, 260 × 211 cm, Musée des Beaux-Arts, Rennes, France. Wikimedia Commons.

Paolo Veronese’s Perseus Rescuing Andromeda followed soon afterwards, in 1576-78. His composition is similar to Titian’s, and equally faithful to the text, but his additional attention to the details of Perseus and Cetus bring this to life, making it one of the finest depictions of this moment.

Félix Edouard Vallotton (1865-1925), Perseus Killing the Dragon (1910), oil on canvas, 160 x 233 cm, Musée d’art et d’histoire de Genève, Geneva. By Codex, via Wikimedia Commons.

Just over a century ago, Félix Vallotton painted one of the most unconventional images of Perseus Killing the Dragon (1910), which might even be a parody of the story, and of narrative painting as a genre.

Andromeda, long freed from her chains, squats, her back towards the action, at the far left. Her face shows a grimace of slightly anxious disgust towards the monster. Perseus is also completely naked, with no sign of winged sandals, helmet of Hades, or the bag containing Medusa’s head. He’s braced in a diagonal, his arms reaching up to exert maximum thrust through the shaft of a spear which impales Cetus through the head. The monster is shown as an alligator, its fangs bared from an open mouth.

Peter Paul Rubens (1577–1640), Perseus and Andromeda (c 1622), oil on canvas, 99.5 x 139 cm, Hermitage Museum, Saint Petersburg, Russia. Wikimedia Commons.

Rubens’ Perseus and Andromeda (c 1622) shows a later moment in which the action is just past, but the outcome is more obvious. Andromeda is at the left, now unchained but still almost naked. Perseus is in the process of claiming her hand as his reward, for which he is being crowned with laurels, as the victor. He wears his winged sandals, and holds the polished shield which still reflects Medusa’s face and snake hair.

One of several putti (essential for the forthcoming marriage) holds Hades’ helmet of invisibility, and much of the right of the painting is taken up by Pegasus, which derive from a different version of the myth. At the lower edge is the dead Cetus, its fearsome mouth wide open.

Two remarkable paintings have told the story using multiplex narrative.

Unknown, Perseus and Andromeda (soon after 11 BCE), from Boscotrecase, Italy, moved to The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, NY. By Yann Forget, via Wikimedia Commons.

This Roman painting from Boscotrecase, near the coast at Pompeii, dates from soon after 11 BCE, and puts the story into a larger landscape, much in the way that later landscape painters such as Poussin were to do.

Andromeda is shown in the centre, on a small pedestal cut into the rock. Below it and to the left is the gaping mouth of Cetus, as Perseus flies down from the left to rescue Andromeda, kill the sea-monster, and later marry Andromeda in reward, as shown in the upper right.

Piero di Cosimo (1462–1521), Andromeda freed by Perseus (c 1510-15), oil on panel, 70 x 123 cm, Galleria degli Uffizi, Florence. Wikimedia Commons.

Piero di Cosimo shows even more events within his large Andromeda Freed by Perseus (c 1510-15). Centred on the great bulk of Cetus, Perseus stands on its back and is about to hack at its neck with his curved sword. At the upper right, Perseus is shown a few moments earlier, as he was flying past in his winged sandals. To the left of Cetus, Andromeda is still secured to the rock by red fabric bindings, not chains, and is bare only to her waist.

In the foreground in front of Cetus are Andromeda’s parents stricken in grief. Near them is a group of courtiers with ornate head-dress. But in the right foreground the wedding party is already in full swing, complete with musicians and dancers.

Over three centuries later, Edward Burne-Jones used a long series of watercolour studies and finished oil paintings to cover the full legend of Perseus, from which I show the two finished paintings telling this episode.

Edward Burne-Jones (1833–1898), The Perseus Series: The Rock of Doom (c 1885-8), oil on canvas, 155 x 130 cm, Staatsgalerie Stuttgart, Stuttgart. Wikimedia Commons.

The eighth of these paintings, The Rock of Doom (1884-5), shows Perseus arriving, and just about to start his negotiations to secure Andromeda’s hand in marriage. Medusa’s head is safely stowed in the kibisis on his left arm. Andromeda is naked, looking coy and afraid with her face downcast.

Edward Burne-Jones (1833–1898), The Perseus Series: The Doom Fulfilled (1888), oil on canvas, 155 × 140.5 cm, Staatsgalerie Stuttgart, Stuttgart. Wikimedia Commons.

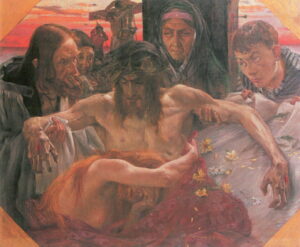

In Burne-Jones’ ninth painting, The Doom Fulfilled (1888), Perseus is swathed in Cetus’ coils with their almost calligraphic form, brandishing his sword and ready to slaughter the monster and bring its terror to an end.

Tomorrow I’ll tell the story of Angelica.