Last Week on My Mac: Why replace your T2 Mac?

In just over a fortnight, when Apple holds WWDC, its annual developer conference, its opening Keynote has to address one salient Mac question: why should you replace your existing Intel Mac with its T2 chip, with a new Apple silicon model with an M3 or M4 chip?

Intel support

The first M1 chips shipped in November 2020, and the last Intel Macs were discontinued a year ago. Over that phase-in period Apple has done well to ensure that faster and more recent Intel models have benefitted from almost everything their M-series successors have enjoyed. When Live Text was first announced three years ago, Apple anticipated it would only be supported on M1 models, but by the time that Monterey was released that autumn/fall, many Intel models were included.

Since then remarkably few features have only been available for Apple silicon. The summary for macOS 14 Sonoma reads:

Video Conferencing, Presenter Overlay

Game Mode

Screen Sharing high performance mode

Siri, works with “Siri” as well as “Hey Siri”.

On MacBook Pro 14-inch and 16-inch 2021 models, Mac Studio, and all Macs with M2 chips, hearing devices can pair direct.

In hardware terms, there are more substantial difference now. Intel Macs don’t support full 40 Gb/s transfer rates with the latest USB4 external SSDs, and to realise comparable read and write performance they’re limited to Thunderbolt 3 SSDs, which are harder to come by, particularly if you want to assemble your own in a good enclosure. Power and energy economy are more obvious, with cooler running and longer battery endurance in Apple silicon notebooks.

For those who like to replace their Macs every three years, those should be good reasons to move up to an M3 or M4 Mac. But is there sufficient distance between architectures to lure those who are still happy with their late Intel models?

Virtualising macOS

One feature that hasn’t yet had as much impact as it should, is virtualisation of macOS on Apple silicon. This is currently constrained by three factors:

Limited versions of macOS. Big Sur can’t be run as a guest OS, and Monterey has substantial shortcomings, making Ventura the oldest version of macOS that has good support as a guest. This is because of limitations built into those older versions of macOS, and can’t be fixed with newer host software.

Limited hardware access. Those currently confined to macOS Monterey or Ventura because of their key audio apps, for example, can’t run those in a VM, another fixed limitation.

Most important of all, lack of support for Apple ID, making a VM incapable of running any App Store apps, or connecting to an iCloud account. I will consider this in more detail in my preview of WWDC nearer the time, but for many potential VM users this makes them incapable of doing anything useful.

Co-processors

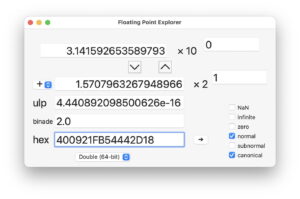

When it comes to co-processors, though, M-series chips are unbeatable. Even the basic M1, which Apple discontinued earlier this month, with its 4P and 4E CPU cores, has a 16-core neural engine and two AMX matrix co-processors. Its more powerful relatives and successors have even more to offer, but those co-processors are probably the least-used parts of the whole chip. After spending many days trying to ‘light up’ the neural engine or AMX co-processors in M1 and M3 chips to study their performance and use, it was clear that almost all the time an Apple silicon Mac is running, they’re either idle or shut down.

Apple first added a neural engine to the A11 seven years ago, initially to enable Face ID, Animoji, and some other specialised tasks. Where available on later chips, including all those used in Apple silicon Macs, they accelerate image analysis such as Visual Look Up and Photos image recognition.

The contradiction here is comparison with PCs, which are only this year gaining dedicated neural engines, although they’re required to support Microsoft Copilot and other features; Apple silicon chips have included powerful neural engines for the last 3.5 years, yet appear to make little use of them.

In just over two weeks, we’ll discover whether Apple is ready to light up those co-processors in its M-series chips, and start putting real distance between them and Intel Macs.