Sea of Mists: Pupils, Thomas Fearnley 2

The Norwegian landscape painter Thomas Fearnley had trained under JC Dahl in Dresden in 1829-30, and painted themes in common with the German Romantic artists, including Dahl and Caspar David Friedrich. In the middle of the 1830s his wanderings around Europe had brought him to the Bernese Oberland in Switzerland, and the Grindelwald Glacier.

Thomas Fearnley (1802–1842), Grindelwald Glacier (1, sketch) (c 1837), oil on canvas, 31 × 40.5 cm, Nasjonalgalleriet, Oslo. Wikimedia Commons.

In about 1837, Fearnley visited the Grindelwald Glacier, and produced this superb plein air oil sketch. In addition to the ghostly-white eagle soaring above the ice, he included more than half a dozen figures, shown in the detail below.

Thomas Fearnley (1802–1842), Grindelwald Glacier (1, sketch) (detail) (c 1837), oil on canvas, 31 × 40.5 cm, Nasjonalgalleriet, Oslo. Wikimedia Commons.

Prominent among the nearer group is a walker, wearing a large black hat. Even the line of people far back against the foot of the glacier has been painted in some detail, though, with the leader holding a staff, and one of them mounted on a pony or similar.

Thomas Fearnley (1802–1842), Grindelwald Glacier (2) (1838), oil on canvas, 157 × 194 cm, Nasjonalgalleriet, Oslo. Wikimedia Commons.

A year or so later, Fearnley painted this large finished version. The method he used to transfer from his original sketch has reversed the sides of the image, but many details have been retained. The eagle still soars, the trees are very similar, but the figures have changed completely.

Thomas Fearnley (1802–1842), Grindelwald Glacier (2) (detail) (1838), oil on canvas, 157 × 194 cm, Nasjonalgalleriet, Oslo. Wikimedia Commons.

On the now lush pastures in front of the massive wall of ice, Fearnley has found a flock of sheep instead of people. In the distance, with his back towards us, is the rambler, posing as shepherd but looking away from the viewer, towards the glacier, and wearing a distinctive black hat.

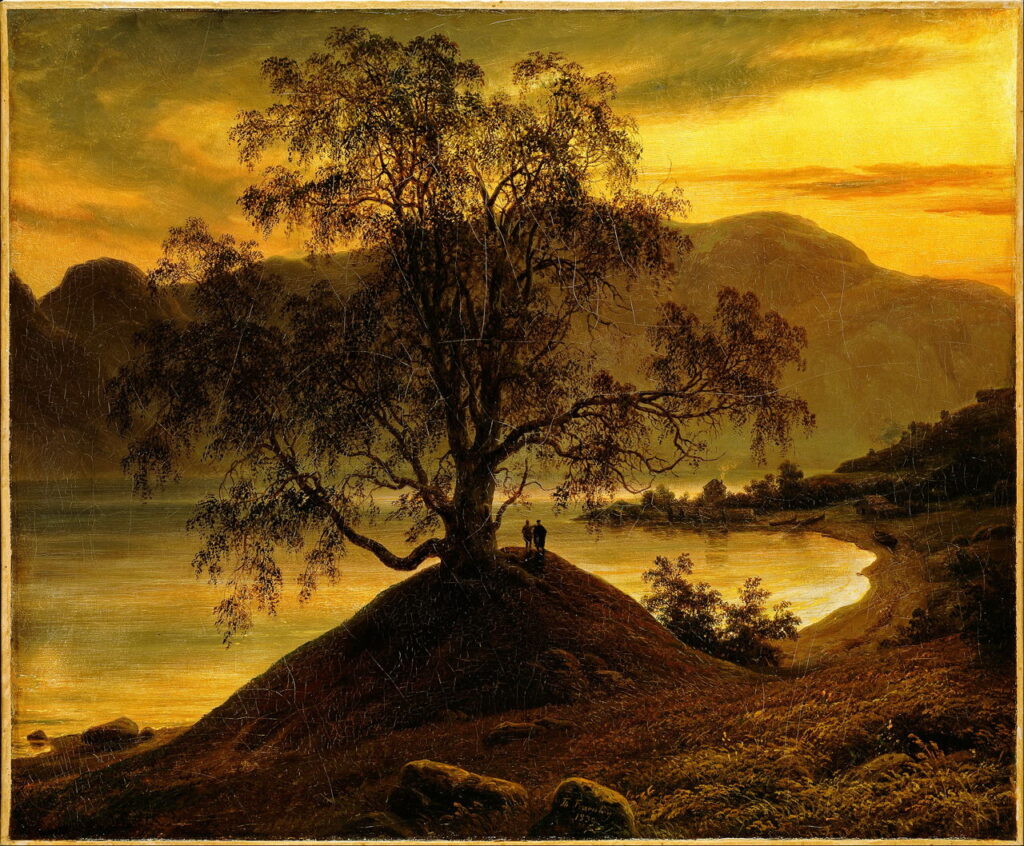

Thomas Fearnley (1802–1842), Old Birch Tree at Sognefjord (1839), oil on canvas, 54.5 x 66 cm, Nasjonalgalleriet, Oslo. Wikimedia Commons.

Back in Norway in 1839, Fearnley’s Old Birch Tree at Sognefjord features two small figures at is centre, and many other absorbing details such as the smoke rising from the chimney of the house on the other side of the small bay. Look closer, at its detail (below) and both figures wear hats, the one on the left being bright red.

Thomas Fearnley (1802–1842), Old Birch Tree at Sognefjord (detail) (1839), oil on canvas, 54.5 x 66 cm, Nasjonalgalleriet, Oslo. Wikimedia Commons.

Using these figures, Fearnley draws the viewer closer and closer into his paintings.

Thomas Fearnley (1802–1842) The Duck Hunter (date not known), oil on paper mounted on panel, 32 × 42 cm, location not known. Wikimedia Commons.

In The Duck Hunter, the figure is camouflaged to increase the challenge made of the viewer. This is heightened in another large finished work, showing The Labro Falls at Kongsberg (1837), below.

Thomas Fearnley (1802–1842), The Labro Falls at Kongsberg (1837), oil on canvas, 150 × 224 cm, Nasjonalgalleriet, Oslo. Wikimedia Commons.

You don’t get many points for spotting the large eagle in the foreground, or the scattered fungi. Rewards increase with the birds wheeling in the sky, and the cabin in the middle distance.

Thomas Fearnley (1802–1842), The Labro Falls at Kongsberg (detail) (1837), oil on canvas, 150 × 224 cm, Nasjonalgalleriet, Oslo. Wikimedia Commons.

To get full marks, you have to notice the tiny red cap among the shadows, to the left of centre in this detail. I think that is Fearnley’s alter ego, collecting brushwood for the fire in his cabin in the upper right.

Fearnley is by no means the only landscape painter to have used these tiny figures to draw the viewer into their highly detailed landscapes, and make them marvel at seeing what they couldn’t have seen in reality. It’s an effective trick that adds interest to a view, and enriches the dialogue between the artist and viewer. The people may be little, but their purpose is as ambitious as the grander landscape around them.

When he was in Munich early in 1842, Thomas Fearnley contracted typhoid, and died there when he was only 39.

Reference

Sumner, Ann, and Smith, Greg (eds) (2012) In Front of Nature, The European Landscapes of Thomas Fearnley, Barber Institute of Fine Arts. ISBN 978 1 907804 10 6.