Delving deep into user accounts in Directory Services

The kernel at the heart of macOS is XNU, standing for X is Not Unix, as, however much macOS might have in common with Unix, once you scratch its surface it’s all very different. Several of you commented recently that what I referred to as a user’s UniqueID should have been termed User ID as it would be in Unix. But dig deeper and you’ll see that macOS does indeed refer to that internally as the UniqueID, because that’s how it’s named for Directory Services in macOS.

Older versions of macOS used to provide advanced options for users in Users & Groups settings, where you could even change a user’s UUID. Then a bright spark thought it would be fun to tell users to change that in a misguided bid to improve their privacy. When someone who seems to know what they’re writing about tells you to do that, you go and try it, don’t you? Only changing a user’s UUID is catastrophic, and most who did so ended up having to rebuild the contents of their Mac from scratch to put the damage right. The lesson is that you should never try anything you don’t understand, for which there’s no simple undo, and which might have serious side-effects. Please don’t do that: it’s such a crazy idea that it’s malicious in intent. As a result, Apple has progressively removed those dangerous advanced user settings, to keep them out of harm’s way.

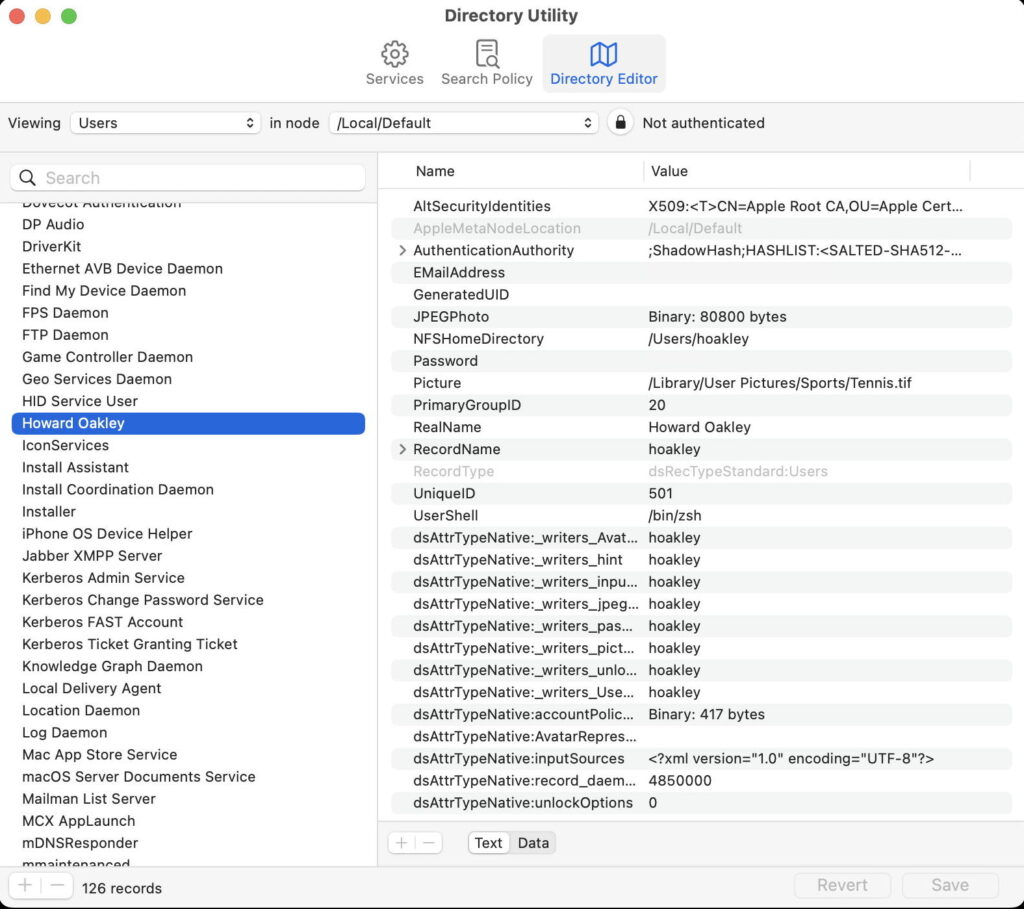

But there are times when you do need to make such changes, or at least check what current settings are. For those you’ll need Directory Services’ editor, Directory Utility, which is carefully hidden in /System/Library/CoreServices/Applications. Whatever you do, please don’t authenticate to Directory Utility, to ensure that you can’t inadvertently change anything that could give you grief.

Modern Directory Services have a long history that I’ll explain on Saturday morning, but they’re basically descended from NeXTSTEP’s NetInfo and the Lightweight Directory Access Protocol (LDAP) implemented in Apple’s successor Open Directory. These flourished in the days of Mac OS X Server, but since then have carried on quietly serving macOS with information about users, groups, and a whole lot more.

Directory Utility may be hidden away, but it’s still well documented, and its Help book is worth browsing. Unless your Mac is connected to a server delivering it LDAPv3, Active Directory or similar services, once you’ve selected the Directory Editor at the top, view Users in the node /Local/Default, as your Mac’s local directory. There you’ll find your personal details, including your UUID as GeneratedUID, your Home folder as NFSHomeDirectory, long user name as RealName, short name as RecordName, and user ID as UniqueID.

Listed as users are many of the services your Mac connects to on your behalf, including the App Store, Apple Pay, Find My and more. Each of these has its own UniqueID, PrimaryGroupID, and more. There may also be hidden users that you thought had been removed, and shared folders from years ago. Don’t give way to any temptation to try ‘cleaning’ this up, as it’s all too easy to wreak havoc unintentionally.

In the past, Directory Utility was commonly used to enable the root user and change its password, features that may still available today in its Edit menu once you’ve authenticated. At one time this was useful, but shouldn’t be used any more unless you’re advised to by Apple.

Directory Utility is now mainly used when integrating a Mac with a network directory server, including Open Directory (formerly in Mac OS X Server), LDAP on a Linux or other server, and Microsoft’s Active Directory. For the advanced user it gathers important information in one place, and every once in a blue moon it can unscramble a Mac or user account that would otherwise require starting from scratch. But please don’t authenticate and start making changes, as you’ll most likely regret it.