macOS updates are shrinking, but what happened to RSRs?

When Apple introduced the Signed System Volume (SSV) in Big Sur, the size of macOS updates rose to their highest ever, as the overhead required for each update reaching 2.2 GB for Intel models and 3.1 GB for Apple silicon. Since then, they have steadily improved in efficiency. This article shows how they have performed in Sonoma, and asks whether Apple has abandoned its Rapid Security Responses (RSRs).

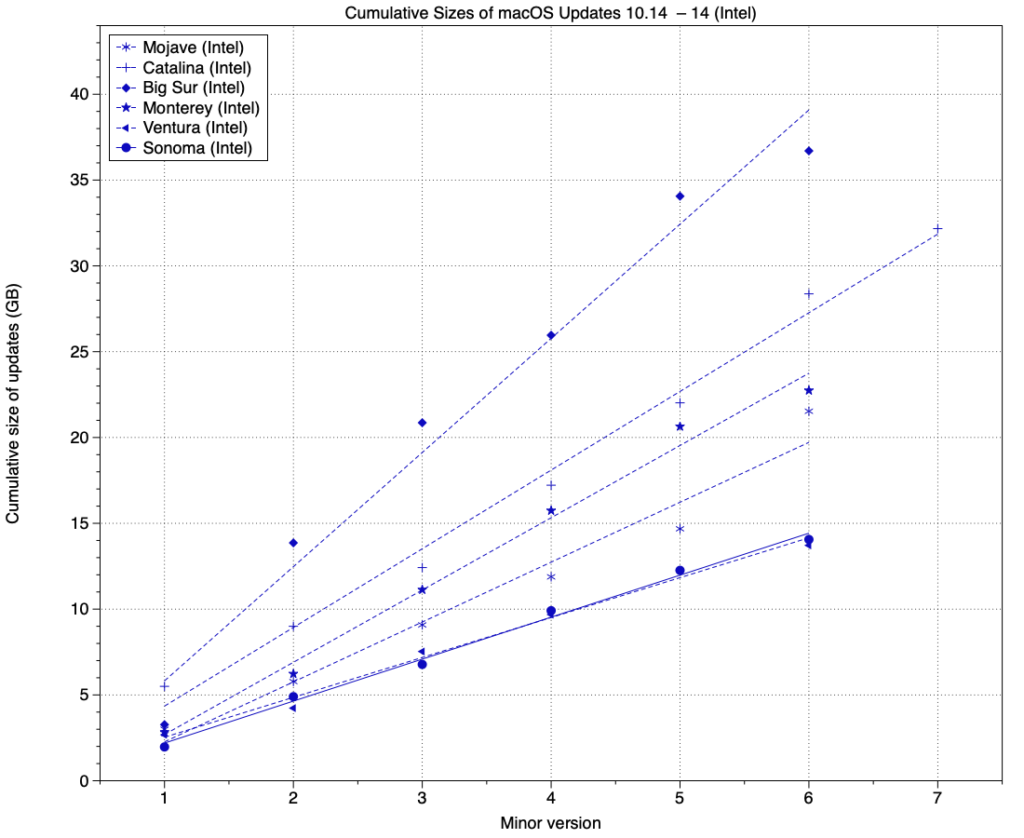

To keep my charts clearer, I here show the two architectures separately.

Total update size

This chart shows cumulative sizes of updates to macOS on Intel Macs from 10.14 Mojave, with its traditional single boot volume, through to macOS Sonoma 14.6. Each point represents the cumulative sum of all updates to that major version of macOS required to reach that minor version. Thus the point for 14.2 is the total of update sizes for 14.1, 14.1.1, 14.1.2 and 14.2. Sizes used aren’t those reported by Software Update, but those of the download itself, as reported in articles here, indexed on this page. That has made a significant difference for some updates for Apple silicon Macs, where the first reported update size has excluded additional architecture-specific overhead. RSRs have been excluded, as they’ve been duplicated in subsequent patch or minor updates. Lines shown are best fits by linear regression.

Update sizes rose markedly from Mojave, with its single boot volume, to Catalina, with its boot volume group, and again to a peak in Big Sur, with the SSV. They fell again as Monterey introduced greater efficiency, and Ventura and Sonoma have been almost identical, and smaller than Mojave.

Apple silicon Macs started with the huge updates of Big Sur, which were even larger than those for Intel models, and benefitted from the improved efficiency of Monterey and Ventura. Unlike Intel Macs, though, Sonoma has seen further reduction in update sizes, although in each update they remain significantly larger than those for Intel models.

Big Sur took a total of 36.7 GB on Intel, and a remarkable 50.07 GB on M1; Sonoma has taken 14.1 GB on Intel, and 21.2 on M1. On Intel, Sonoma required 38% of the update size as Big Sur; on M1, that proportion was slightly higher at 42%. Apple silicon updates were 136% the size of those for Intel models in Big Sur; in Sonoma that ratio has risen to 150%.

Minimum update sizes were about 400 MB for Intel, and 820 MB for Apple silicon, which must be close to the overhead required for macOS updates for the two architectures. These reflect the size of the ‘Update Brain’ required to install each update, and all bundled firmware updates. The latter have been steadily reducing as Intel updates have supported fewer models without T2 chips, but have remained the same if not grown for the substantially larger firmware updates for Apple silicon’s Secure Boot.

Unscheduled updates

Sonoma reached version 14.6 without an excessive number of patch updates. The number of patch versions released between the x.0 and x.6 scheduled versions ranges from 4 (Monterey) to 6 (Bug Sur, Ventura), with Sonoma taking just 5, although 14.6 has been closely followed by 14.6.1 in what appears to be a bug fix rather than the first security update.

What has been surprising is that Apple has released no RSRs for Sonoma, not one. The last RSR was the second released for 13.4.1 more than a year ago, on 12 July 2023. RSRs were introduced to Ventura in May 2023 as a method of replacing some components of macOS that aren’t installed in the SSV but in separate cryptexes, cryptographically verified disk images stored on the hidden Preboot volume. They were intended to let Apple promulgate important fixes to vulnerabilities in Safari, WebKit, and some other bundled components without waiting for a full macOS update. Unfortunately, Apple’s second RSR in July last year was fumbled badly when it broke Safari access to many popular websites including Facebook, and had to be replaced three days later.

Although it’s never clear when a patch update could have been issued as an RSR, Sonoma 14.1.2 should have been a candidate as it’s only reported to have fixed two vulnerabilities in WebKit, that appeared to have been addressed in Safari-only updates for macOS 12 and 13. It looks now as if Apple’s initial enthusiasm for RSRs has cooled, and they’re unlikely to be significant in the future.

Standalone updaters

Updates to macOS Catalina and earlier were also available in downloadable standalone installer packages. Apple discontinued those, amid much protest from users, when it introduced Big Sur. Although there were some suggestions that they might return in the future, as the new update mechanism matured, there has still been no sign of them. Currently the only form of updater available is the full macOS Installer app, typically over 13 GB in size. This remains a shortcoming compared with Catalina and earlier, but it appears that standalone updaters aren’t missed by most Mac users, or at least that Feedback to Apple has been insufficient to produce a response.

Major updates

Prior to macOS Ventura, upgrading to the first release of the next major version of macOS required downloading its full installer app. Although larger than necessary to perform the upgrade, it was relatively error-proof, as the user had to intentionally start the app’s installation process, which could also be cancelled once it was in progress.

Ventura was the first major version for which Software Update used a mechanism similar to that for minor updates, and didn’t download a discrete macOS installer app. As Apple hadn’t warned of that, it caught some users by surprise, when they found their Mac was being upgraded almost automatically. This was repeated with the release of Sonoma, and the problem compounded when some users appear to have been upgraded without their consent.

As Tom Bridge has pointed out, this requires smaller downloads that install considerably faster, but, on Intel Macs at least, don’t require user consent or authentication.

Apple is likely to employ the same update mechanism when it releases Sequoia and takes us on to the next cycle.